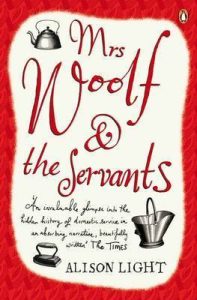

Alison Light’s 2007 book Mrs. Woolf and the Servants – referred to by me here – is indeed a wonderful read, and for many reasons. Significantly, it goes some way in satisfying my curiosity about the complicated relationship of the said Mrs. Woolf with her servants, and, more generally, in offering through this particular example an engrossing and informative account of the domestic power structures of the middle and upper class households (in Britain), and as a microcosm of the hierarchical distribution of power in greater society, from the end of the Victorian era through to the post-war twentieth century. The gap in my own knowledge was quickly apparent – and gaping! – and Light’s book has gone some considerable way towards remedying my ignorance.

Even from the prologue, I was heartened to read that Alison Light’s motivation for writing the book came from her reading of Virginia Woolf’s diaries and her discomfort, on one hand, and fascination on the other, with Woolf’s language concerning her domestic help over the years, and like me especially with respect to Nellie Boxall. (And I must add: it was just as heartening to hear a British scholar of such standing – and to the Left! – admit to her previous ignorance of the historical importance of domestic service in Britain, and especially for women.)

Broadly chronological, the book traces the history of domestic servitude parallel to that of Virginia Woolf’s life. But ‘parallel’ is a misplaced word here (when thinking about time it may always be!); more precisely, these lives and histories are intertwined in ways obvious and not so; imbued with a public presence that abides by social norms, and a behind closed doors intimacy that is mutually dependent (and, as Light says, unequal); in both spheres easily sentimentalized – then and now.

Woolf is not necessarily the star of this narrative, but rather the accompaniment for the lives of others: of Sophie Farrell, the treasure of the Stephan household in late-Victorian Hyde Park Gate, of Nellie and Lottie Hope, inseparable, in service and out, almost a life long, and of the Batholomews and Annie Thompsett and the Haskins and Louie Everest all who made Monks House the “home” Woolf had needed for her emotional well-being and creative and professional development as a writer. Would she have been generous in accepting this supporting role? I think so, I hope so.

And, as employers, the Woolfs are hardly set decorations – it is important what Light has to say about their role as representative of an intellectual class in the first half of the twentieth century: the disparity that existed between the political and societal agenda that was being propagated and the actuality of a way of life that contributed to the cementing of rigid class structures. I think it is fair to say that it was the highly political Leonard who spoke and wrote loudest on the rights of the working class, but maintained an imperious attitude to those employed in his own home.

I knew of course that the Woolfs inherited – so to speak – Lottie and Nellie from Roger Fry (and I have learnt to be alerted to anything concerning the extraordinary Fry family – Light suggests in her notes that a collective biography is in order!) and, as his essay A Possible Domestic Architecture written around about the time he was building a new home in Guildford suggests, Lottie and Nellie would have at, this, the beginning of their “Bloomsbury” career, been exposed to circumstances and surroundings that were an eccentric mix of the the baroque and the modern. Certainly they would have enjoyed during their time at “Durbins” at least a taste of domestic modernity – in both less formal manner and technical advancement; that would not play a role in the Woolf household(s) for quite some some time to come. (Not directly relating to Nellie and Lottie, but I embed below are a couple of images relating to Fry’s “Durbins” project for future reference.)

Inner mural

For her enthusiasts, this book will add a new dimension to a never quite satisfied understanding of Virginia Woolf’s life; in its many facets and contradictions, and for those who are not necessarily or not at all, an unusual and critical introduction to one of the most fascinating women writers of the twentieth century. And to any discerning reader, Mrs. Woolf and the Servants is a lively and persuasive socioeconomic study that says a lot about how generations (of mostly women) were trapped in a system of family and work that crossed the prevailing lines of class and, just as importantly, how the demise of domestic servitude through war and emancipation and war again and all the ensuing societal transformations, led to the breaking down of a vicious circle and the creation of new opportunities – at home and at work, and for those of all classes and especially for women.

Towards the end of her book, Alison Light reflects upon Virginia Woolf reflecting upon the essential character of a life, of how it is to be explained – what remains when it’s all said and done. With her mental well-being in decline and as a means of dealing with the harsh reality of the approaching war, she flees into the past and begins writing her memoirs. Says Light:

She wrote again about her mother […]but this time she noted how unreliable memory was [she was unravelling] the idea of plotting a life when life had no plot […]the memoirs recognised that [‘self’] was an illusion: the inner-life was crowded with others […] she moved […] to the larger questions of the group, how classes and other forces shape the world inside.

Mrs. Woolf and the Servants, p. 257 (Kindle Ed.)

It seems to me, in what was to be the last year or so of her life, Woolf was, not retreating from her inner-life from which so much of her creativity sprung and which had so often offered her refuge in the darkest times, but was allowing others in – rather, recognizing their presence all along and their role in forming she, Virginia Woolf. Light paraphrases (in English) Woolf quoting (in French) George Sand at the end of Three Guineas (1938): “…Individuality has by itself alone no meaning or importance at all. It takes on meaning only in being a part of the general life…” [p.271]

The immense interest in her life in recent decades, leads one sometimes to wonder whether there is much we don’t know about Woolf’s life – she and others have told us enough after all. But even if we are tempted to do so – and, of course we are not! – facts aren’t everything. Alison Light’s book adds an essence of something more. And that essence comes from giving lives to others, to Sophie, to Nellie and Lottie, to Mabel and … Vibrant, interesting lives, beyond that of Woolf and her cohorts – lives of their own.

Several things came together that encouraged me to read Alison Light’s book. A train of thought that began in a German newspaper’s publication of a speech made by Leïla Slimani in which she references a Virginia Woolf essay that deconstructs the Angel in the House metaphor of the Victorian era and attempts to reconstruct the modern woman, and continued to a French book – Slimani’s Lullaby – and recognizing an almost grotesque development in domestic relationships into post-modern times. Something I am reasonably sure Leïla Slimani was also thinking about.

Finally, one can wonder whether all those angels in all those houses and, importantly in terms of this lektüre, all those in their ‘service’, were ever truly released from the defining constraints of a social order. In the 1930s, as Woolf was considering them anew, their clipped wings may have been sprouting anew – ready for flight – but through each successive generation, whilst the plumage may have been (and is) of a different hue and texture, it was always being plucked at, the sinews too tenuous, never quite fulsome to soar, to set them free; too heavy the burden of history, the interests of power and capital (and man, maybe) – intent on keeping the flighty firmly grounded.