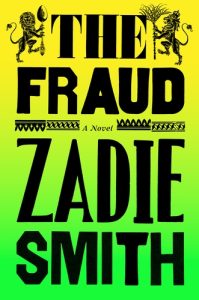

Given that Robert Penn Warren’s 1946 novel All the King’s Men has maintained its reputation as one of the most lauded of American 20th century works of political fiction, I abstain here from too much (unqualified) comment. But I feel like I have to write something for it is a work of such merit and is, in my opinion, incredibly relevant to the contemporary political landscape.

A couple of years ago I saw a 2006 movie adaptation of the novel on Netflix with Sean Penn as Willie Stark; presumably a box-office flop and only tepidly received by critics but liked immensely by this person (that is, ME). Watching it at the time, I recall only being able to think of Donald Trump; by then out of office if not out of mind (HIS or mine I am not sure!), and confined to the annals of history one could have thunk. Well, one could have…! Alas. After his reelection in November, I was reminded again of Warren’s book and so, over the holidays (and for the first time), turned to the original stuff. And I had not been deceived, he (TRUMP) ghosts his way through the entire narrative. But not only does HE, but also a particular brand of populism that once set alight, blazes, may diminish, but continues to smoulder, ever ready to flare up again.

Now I have no idea when Trump became TRUMP, but one can follow Willie Stark as he progresses from an ambitious wannabe to THE BOSS, and one can follow, too, those around him facilitating his ascendancy. For instance, I was particularly taken by this exchange between the still-fledgling candidate and his runaround Jack Burden (the novel’s narrative voice) who, in an attempt to salvage the floundering gubernatorial campaign, launches into a rare tirade in an effort to persuade Willie to change tack – to forsake his formulaic, heavy-on-detail speeches for an oratory style with more, shall we say, entertainment value:

[…Willie says:] “They didn’t seem to be paying attention much tonight. Not while I was trying to explain about my tax program.”

[Jack:] “Maybe you try to tell ’em too much. It breaks down their brain cells. […] Just tell ’em you’re gonna soak the fat boys and forget the rest of the tax stuff.”

[Willie:] “What we need is a balanced tax program. Right now the ratio between income tax and total income for the state gives an index that -“

[Jack:] “… they don’t give a damn […] Hell, make ’em cry, make ’em laugh, make ’em think you’re their weak erring pal, or make ’em think you’re God Almighty. Or make ’em mad. Even mad at you. Just stir ’em up, it doesn’t matter how or why, and they’ll love you and come back for more. Pinch ’em in the soft place. They aren’t alive, most of ’em and haven’t been alive in twenty years. Hell, their wives have lost their teeth and their shape, and likker won’t set on their stomachs, and they don’t believe in God, so it’s up to you to give ’em something to stir ’em up and make ’em feel alive again. Just for half an hour. That’s what they come for. Tell ’em anything. But for Sweet Jesus’ sake don’t try to improve their minds.”

-“All the King’s Men” (Penguin Modern Classics) [p.108]

Now if that ain’t the winning formula for a Trumpian scorched earth rally! A major difference of course is that nobody has needed to nudge Trump; what Willie had to learn, Trump seems to know instinctively.

Embedded below is a sample reading of the first chapter of this legendary novel from the U.S. publisher’s website. For the uninitiated: Think Faulkner just not as difficult, the Deep South almost palpable – the heat, the poverty, the religious (irreligious, and anything else) fervor, the politicking, the corruption. Then exchange Louisiana for Queens, rural poverty for urban wealth – inherited both, Willie Stark or Huey Long (an inspiration for Stark, though one which Warren sought to minimize) for Donald Trump, and you can imagine your way to the here and now. Mag(a)nificent (sic) – to imagine, that is. In reality anything but.