My reading project

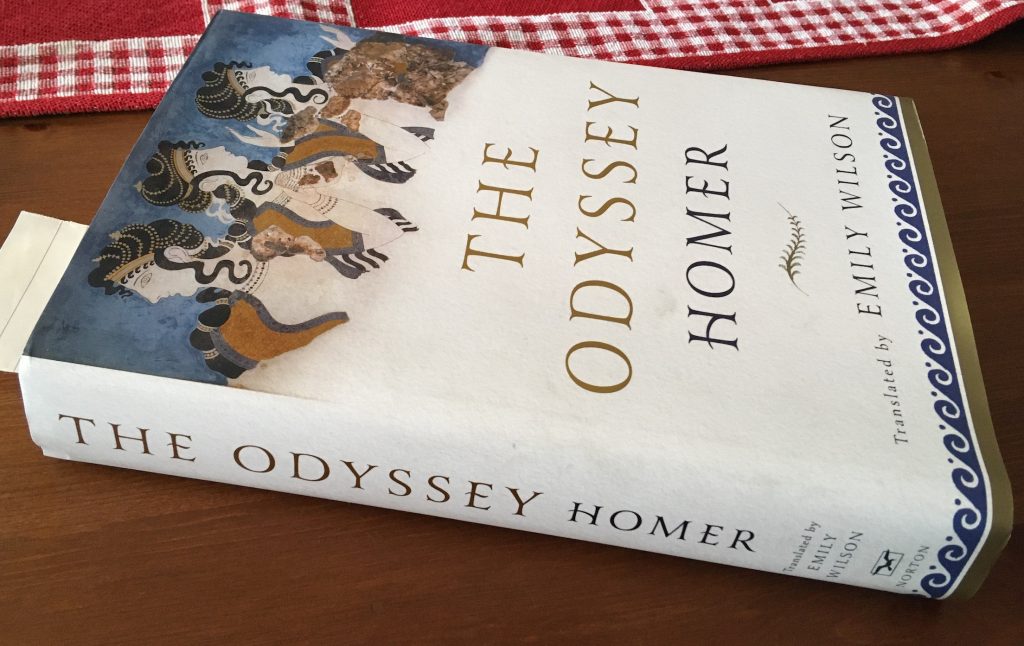

As a special project in this new year 2020, I intend to embark upon a personal and concentrated reading of Emily Wilson’s celebrated 2018 translation of Homer’s “The Odyssey”, and will regularly write some posts to accompany my progress. Whether I can be as industrious as Penelope during her long tormented wait for Odysseus’ return is debatable!

To avoid the complication of having a separate blog, I’ll categorise and number in brackets each post (as in the header above) pertaining to my readings; collated, together with other related material, they will then be accessible as My Odyssey Reading from the main menu.

Page numbers, Book titles and other references will be cited from my hardback first edition copy: Homer, The Odyssey, trans. by Emily Wilson, First Edition, New York: W.W. Norton, 2018

writer and translator

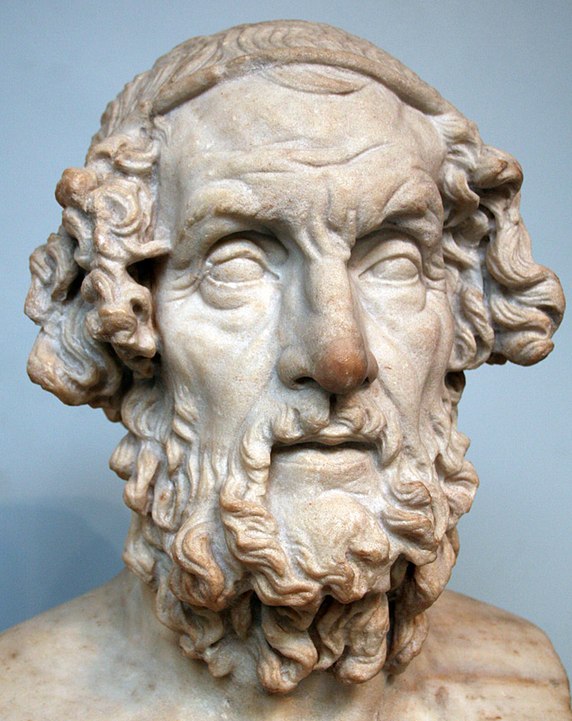

Before getting to the book and the really very substantial introductory pages therein, firstly an introduction to the writer, poet, composer, and all the plurals of the same, that we call simply Homer, and his, her, their most recent translator Emily Wilson.

Whilst legends persist (the blind bard for instance) and are certainly not without interest, whether there was this one Homer to whom can be attributed the epic works of The Iliad and The Odyssey is debatable. I very much like the idea of differentiating between a historical Homer and the poet Homer, which is probably not a terribly original thought but it seems to me a bit like the way of, for instance, approaching the historical Jesus alongside he explained through the lens of Christian dogma. Also, it may be that in a literary sense, identification is better explained through the more generalised “Homeric Question”; answered also with many a dissenting voice but all with the emphasis on Homer as an oral tradition.

Unlike Homer, Emily Wilson is absolutely one real person and has a website and can speak for herself, but briefly: Wilson is a British classicist born into the right family to therefore be educated at the right places to now be Professor of Classics at University of Pennsylvania, celebrated overnight it seems with the publication of her translation and she is, loathe that I am to mention it, since the Summer a recipient of one of these so-called genius grants. None of which I begrudge her, and mercifully, though she may sound a twee bit posh, I don’t think she would hang high the “genius” label! Following is a really interesting lecture she gave in September at Columbia University, focusing on her Odyssey translation, but with more generalised remarks on her method of work.

Also, I think Emily Wilson would have appreciated this review by Gregory Hays in The New York Times with its imperative on the nuance that she brings to her translation, and this is a nice magazine piece also in the Times. Together they say something about the person as scholar and translator, and the very special art of translation. Further links I will add to the sidebar menu.

In the coming days I will post some thoughts on Wilson’s introductory and translator notes – interesting enough in themselves I must say. I am really quite excited about this (Winter!) reading project; in itself an odyssey of sorts. My only encounter in any meaningful way with classics has come in recent years via Gregory Nagy’s edX course The Ancient Greek Hero (which may be caught in a new iteration) and the private reading and study that it encouraged, so the best I can do here is present the observations of an everyman, -woman.

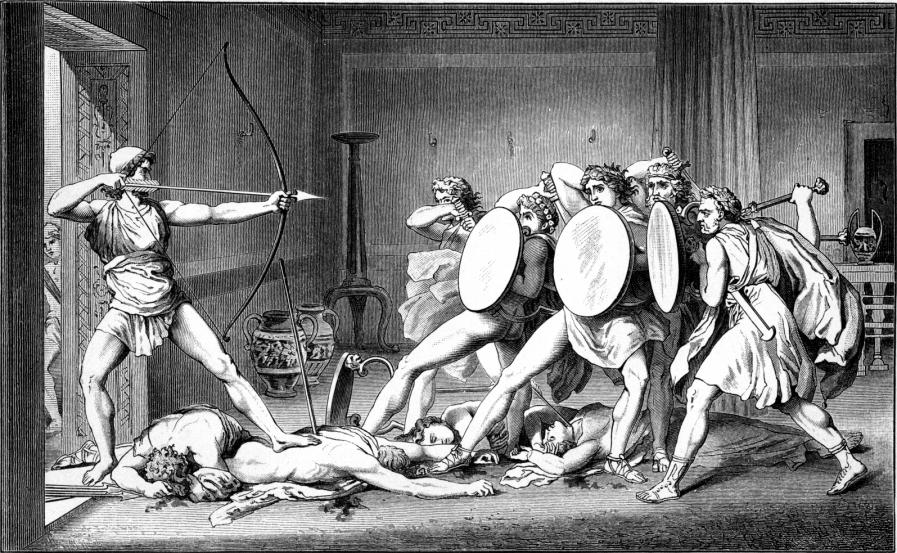

Famously, The Odyssey has 24 books or scrolls, but my ambitions do not stretch to writing systematically on every one of those, instead I’ll condense the purely narrative and concentrate on more thematic aspects that I find to be particularly thought-provoking.