This article was first published on September 23, 2020 in The Conversation and is republished here under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

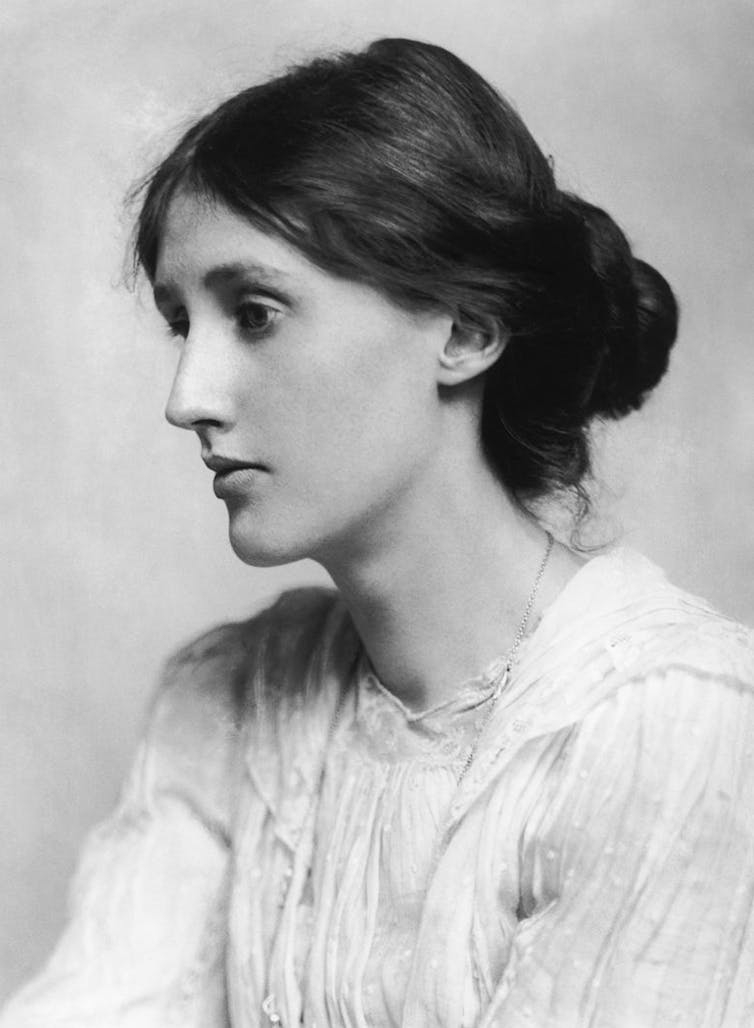

Guide to the classics: A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf’s feminist call to arms

Jessica Gildersleeve, University of Southern Queensland

I sit at my kitchen table to write this essay, as hundreds of thousands of women have done before me. It is not my own room, but such things are still a luxury for most women today. The table will do. I am fortunate I can make a living “by my wits,” as Virginia Woolf puts it in her famous feminist treatise, A Room of One’s Own (1929).

That living enabled me to buy not only the room, but the house in which I sit at this table. It also enables me to pay for safe, reliable childcare so I can have time to write.

It is as true today, therefore, as it was almost a century ago when Woolf wrote it, that “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction” — indeed, write anything at all.

Still, Woolf’s argument, as powerful and influential as it was then — and continues to be — is limited by certain assumptions when considered from a contemporary feminist perspective.

Woolf’s book-length essay began as a series of lectures delivered to female students at the University of Cambridge in 1928. Its central feminist premise — that women writer’s voices have been silenced through history and they need to fight for economic equality to be fully heard — has become so culturally pervasive as to enter the popular lexicon.

Julia Gillard’s A Podcast of One’s Own, takes its lead from the essay, as does Anonymous Was a Woman, a prominent arts funding body based in New York.

Even the Bechdel-Wallace test, measuring the success of a narrative according to whether it features at least two named women conversing about something other than a man, can be seen to descend from the “Chloe liked Olivia” section of Woolf’s book. In this section, the hypothetical characters of Chloe and Olivia share a laboratory, care for their children, and have conversations about their work, rather than about a man.

Woolf’s identification of women as a poorly paid underclass still holds relevance today, given the gender pay gap. As does her emphasis on the hierarchy of value placed on men’s writing compared to women’s (which has led to the establishment of awards such as the Stella Prize).

Invisible women

In her book, Woolf surveys the history of literature, identifying a range of important and forgotten women writers, including novelists Jane Austen, George Eliot and the Brontes, and playwright Aphra Behn.

In doing so, she establishes a new model of literary heritage that acknowledges not only those women who succeeded, but those who were made invisible: either prevented from working due to their sex, or simply cast aside by the value systems of patriarchal culture.

To illustrate her point, she creates Judith, an imaginary sister of the playwright Shakespeare.

What if such a woman had shared her brother’s talents and was as adventurous, “as agog to see the world” as he was? Would she have had the freedom, support and confidence to write plays? Tragically, she argues, such a woman would likely have been silenced — ultimately choosing suicide over an unfulfilled life of domestic servitude and abuse.

In her short, passionate book, Woolf examines women’s letter writing, showing how it can illustrate women’s aptitude for writing, yet also the way in which women were cramped and suppressed by social expectations.

She also makes clear that the lack of an identifiable matrilineal literary heritage works to impede women’s ability to write.

Indeed, the establishment of those major women writers in the 18th and 19th centuries (George Eliot, the Brontes et al), when “the middle-class woman began to write” is, Woolf argues, a moment in history “of greater importance than the Crusades or the War of the Roses”.

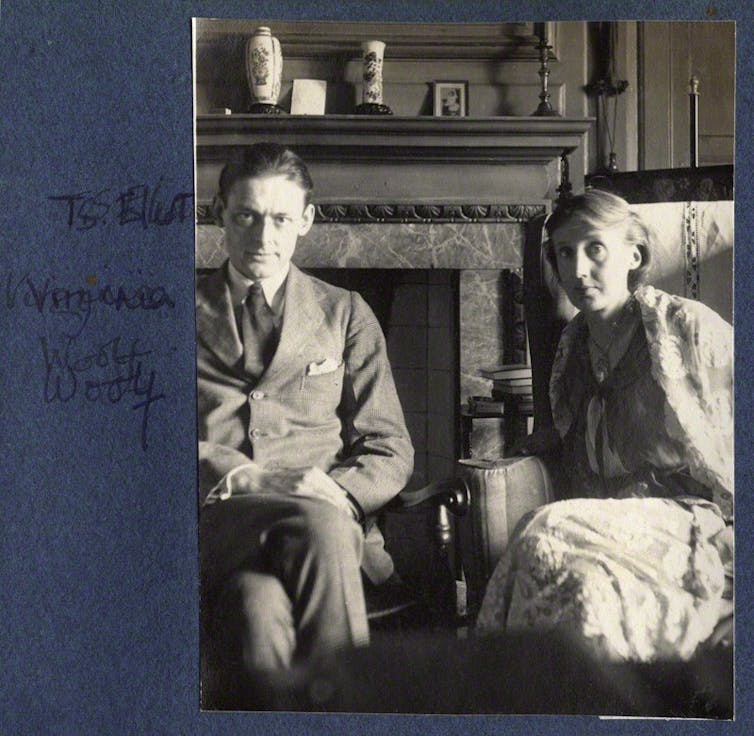

Male critics such as T.S. Eliot and Harold Bloom have identified a (male) writer’s relation to his precursors as necessary for his own literary production. But how, Woolf asks, is a woman to write if she has no model to look back on or respond to? If we are women, she wrote, “we think back through our mothers”.

Her argument inspired later feminist revisionist work of literary critics like Elaine Showalter, Sandra K. Gilbert and Susan Gubar who sought to restore the reputation of forgotten women writers and turn critical attention to women’s writing as a field worthy of dedicated study.

All too often in history, Woolf asserts, “Woman” is simply the object of the literary text — either the adored, voiceless beauty to whom the sonnet is dedicated or reflecting back the glow of man himself.

Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size.

A Room of One’s Own returns that authority to both the woman writer and the imagined female reader whom she addresses.

Stream of consciousness

A Room of One’s Own also demonstrates several aspects of Woolf’s modernism. The early sections demonstrate her virtuoso stream of consciousness technique. She ruminates on women’s position in, and relation to, fiction while wandering through the university campus, driving through country lanes, and dawdling over a leisurely, solo lunch.

Critically, she employs telling patriarchal interruptions to that flow of thought.

A beadle waves his arms in exasperation as she walks on a private patch of grass. A less-than-satisfactory dinner is served to the women’s college. A “deprecating, silvery, kindly gentleman” turns her away from the library. These interruptions show the frequent disruption to the work of a woman without a room.

This is the lesson also imparted in Woolf’s 1927 novel To the Lighthouse where artist Lily Briscoe must shed the overbearing influence of Mr and Mrs Ramsay, a couple who symbolise Victorian culture, if she is to “have her vision”. The flights and flow of modernist technique are not possible without the time and space to write and think for herself.

A Room of One’s Own has been crucial to the feminist movement and women’s literary studies. But it is not without problems. Woolf admits her good fortune in inheriting £500 a year from an aunt.

Indeed her purse now “breed(s) ten-shilling notes automatically”.

Part of the purpose of the essay is to encourage women to make their living through writing.

But Woolf seems to lack an awareness of her own privilege and how much harder it is for most women to fund their own artistic freedom. It is easy for her to advise against “doing work that one did not wish to do, and to do it like a slave, flattering and fawning”.

In her book, Woolf also criticises the “awkward break” in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847), in which Bronte’s own voice interrupts the narrator’s in a passionate protest against the treatment of women.

Here, Woolf shows little tolerance for emotion, which has historically often been dismissed as hysteria when it comes to women discussing politics.

A Room of One’s Own ends with an injunction to work for the coming of Shakespeare’s sister, that woman forgotten by history. “So to work, even in poverty and obscurity, is worthwhile”.

Such a woman author must have her vision, even if her work will be “stored in attics” rather than publicly exhibited.

The room and the money are the ideal, we come to see, but even without them the woman writer must write, must think, in anticipation of a future for her daughter-artists to come.

An adaptation of A Room of One’s Own is currently at Sydney’s Belvoir Theatre.

Jessica Gildersleeve, Professor of English Literature, University of Southern Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.