This article was first published on December 2, 2020 in The Conversation and is republished here under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A philosophical idea that can help us understand why time is moving slowly during the pandemic

Matyáš Moravec, Durham University

Many people feel that their experience of time has been a bit off this year. Even though the clocks are ticking as they should be, days stretch out and some months seems to go on forever. We all know that there are 60 seconds in a minute but 2020 has made us all aware of how we can experience the passage of time a bit differently.

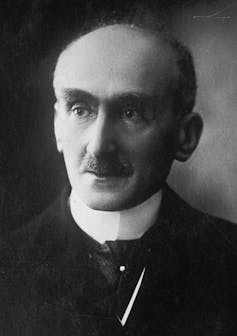

The French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859-1941), who was a bit of a celebrity in his time, came up with an idea that can help us understand why time has felt so strange in the year of the pandemic, la durée.

Bergson argued that time has two faces. The first face of time is “objective time”: the time of watches, calendars, and train timetables. The second, la durée (“duration”), is “lived time,” the time of our inner subjective experience. This is time felt, lived, and acted.

Living on our own time

Bergson observed that we mostly don’t pay attention to la durée. We don’t need to — “objective time” is far more useful. But we can get a glimpse of the difference between them when they come apart.

The stretch of objective time between 3pm and 4pm is the same as that between 8pm and 9pm. But this does not have to be so with la durée. If the first interval is spent waiting at the dentist’s office and the second at a party, we know the first hour drags and the second just passes by too quickly.

An example of this that Bergson would have loved can be found in a highly unlikely place, the 1998 animated film AntZ. In a short scene halfway through the film, two ants get stuck to the soles of a boy’s shoes. The two-minute sequence involves them talking to each other while the boy takes four or five individual steps.

In the scene, talking happens in normal time while the steps happen in slow motion. The filmmakers have managed to squeeze two durées of different speeds into one sequence: the boy walks in slow motion, while the ants converse in real time. None of this can be captured if we took a stopwatch and noted the precise positions of the shoes and the content of their conversations. “Objective time” is just irrelevant to the description of the scene: the ants’ durée really matters to the viewer.

The pandemic slow down

If we shift our focus from “objective time” to la durée, we can put our finger on the feeling of strangeness surrounding time this year.

It’s not just that that for many la durée slowed down during lockdown and sped up towards the relatively restriction-free summer.

For Bergson, no two moments of la durée can ever be identical. The arrival of a train at a particular moment of objective time is always the same. But our past feelings and memories influence our present experience of time. People who were lucky enough to not have to cope with the negative effects of the pandemic might have felt a sense of “novelty” about the first lockdown: the sales of exercise equipment rose sharply, some started learning Welsh, others began making bread. The reason why we often struggle to get into the same mindset now is that the memory of the first lockdown “flavours,” as Bergson would say, the current one. Countless yoga-mats will end up behind cabinets as we recall how fed up we got having to stay inside the first time around.

For Bergson, the “speed” of la durée is also connected to human agency, which is always influenced by subjective and specific memories of the past and shaped by anticipation of the future. So it is not just the passage of time in the present that is messed up. The pandemic has distorted both our ideas of the past and the future in ways that “objective time” cannot capture. If we now look into the past, we realise that trying to remember exactly how many months ago the Australian bushfires were raging is quite hard but that it was this year and before the pandemic.

Similarly, if we look forward to the future, our feelings about stretches of time between now and the future are distorted. When will we go on holiday? How long will it be before we see our loved ones? Without signposts in objective time, we feel that time passes – but because nothing happens it passes much more slowly and we’re stuck in the present. If we knew for certain now that the world would be back to normal in three months, la durée would pass more quickly. But since we don’t know, it drags – even though things might, in the end, turn out to be back to normal in the same stretch of objective time.

In 1891, Bergson married the cousin of the novelist Marcel Proust (1871-1922), whose writing was strongly shaped by Bergson’s durée. Proust’s monumental In Search of Lost Time — the longest novel ever written — illustrates the ability of la durée to contract and expand, regardless of objective time. As we read, the progression of Proust’s lived time feels natural. And yet each volume passes in a different “objective” time: some volumes span years, others just a couple of days, despite the fact that they’re all roughly the same length.

The year of the pandemic was much like this. The time of calendars measuring out days and weeks became irrelevant — the durée we lived in took over.

If we accept Bergson’s more controversial claim that only la durée is “real” and objective time is merely an external construction imposed upon our lives, one might say that the pandemic has given everyone an insight into the fundamental nature of time.

Matyáš Moravec, Postdoctoral research associate, Durham University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.