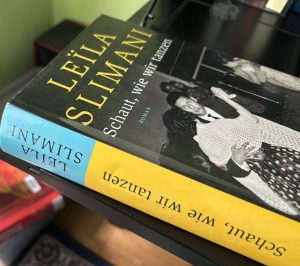

Le Pays des autres 2: Regardez-nous danser (read by me in German as Schaut, we wir tanzen, and available in English translation as Watch Us Dance) continues Leila Slimani’s family saga; a fictional dive into the colorful, often murky and treacherous depths of her own dynastic history, the first part of which I wrote enthusiastically about here and which ended with the beginning of the end of colonial rule in Morocco.

When the story continues, it is the summer of 1968 and more than a decade has passed since Morocco gained its independence from France (in 1956), but the country is struggling now under another – this time home-grown – brand of tyranny: defined through its authoritarian monarch, a brutal police and judicial system in cahoots with a corrupted elite and a patriarchal hegemony. It is to this Morocco that Aïcha, who so entranced with her intelligence and originality as a little girl, returns after some years studying medicine in Strasbourg. For one summer – and then perhaps a lifetime. One is tempted to say: she returns to the fold. But that is something for sheep, and an instinctive follower is this young woman not. Nor lost, nor castout. Rather it is to the bosom of her family in Meknès that she returns; their fortunes having risen in the ensuing years and now with a place amongst a burgeoning new marocaine bourgeoisie. The reader remains alert still to Aïcha’s contrariness: her self-possession and her selflessness; her wanting to please and her not giving a fig; her intellectual rationality and discipline and her emotional inner-life and flights into religious mysticism. One empathizes with Aïcha, with each dilemma she faces (and faces down) – her love of family, of friends and two nations; and the loyalties demanded and the conflicts that ensue – always knowing that the latest will be not the last.

And because she so fascinated me in In the Country of Others, I concentrate on Aïcha (and I suspect Slimani developed her character to be the focus – clearly inspired by her mother but also with a good dose of self one could think), others in the Belhaj family have central moments; both individually and in their interactions amongst each other. (The changing perspectives are – along with her blissfully short and elegant sentences – a defining quality of Slimani’s writing.) Aïcha’s parents, Amine and Mathilda, of course: the very personification of two nations in co-habitation; each with their own truth, intimately attached and profoundly detached, forgiving and unforgiving in equal measure. It is not always clear who is controlling whom. But there is a sort of love, that is frayed, tested, rarely acknowledged – and a lot of regret. The radical choices of Amine’s siblings, Omar and Selma, have only become more so since the first book. But this story here is one of more youthful years spent during a time of immense social and political upheaval, and so Aïcha’s path is very much juxtaposed against that of her younger brother Selim – restless, sexually awakened in ways unexpected. As Aïcha returns to the nest so does Selim take wing.

Aïcha pursues her career in obstetrics. Aïcha marries Mehdi – once, theoretically, a Marxist, now, practically speaking, beholden to the government. The book ends in 1971; the king has survived an assassination attempt, and Aïcha has brought her own child into the world.

Explicit in the title, dancing can be extended from the very reality of the clubs and bars of Casablanca and beyond where the young of Morocco gather to a metaphorical place; for it is a heady time of post-colonial uncertainty when power dynamics have changed and can be visualized as two parties skirting around each other, conscious of their position in any one moment, but unsure of their next step, and this reflected in the age-old story of when boy meets girl, of codes and signals, of swirling skirts and feigned youthful insouciance. Dualities abound in Leïla Slimani’s narrative, and this series could be well described as a pas de deux, whereby here there are no clear partitions; each blends into the next; from the entrée to the adagio and with some variations. I await with anticipation the continuation and culmination (coda) – presumably due from Gallimard this year or next.

Did I mention the translation? No, I did not. Translators should always be credited. I know enough to be quite confident that Amelie Thoma captures Slimani’s literary voice beautifully in German. (Of the English translation I cannot say, but Sam Taylor has creds so to speak!)