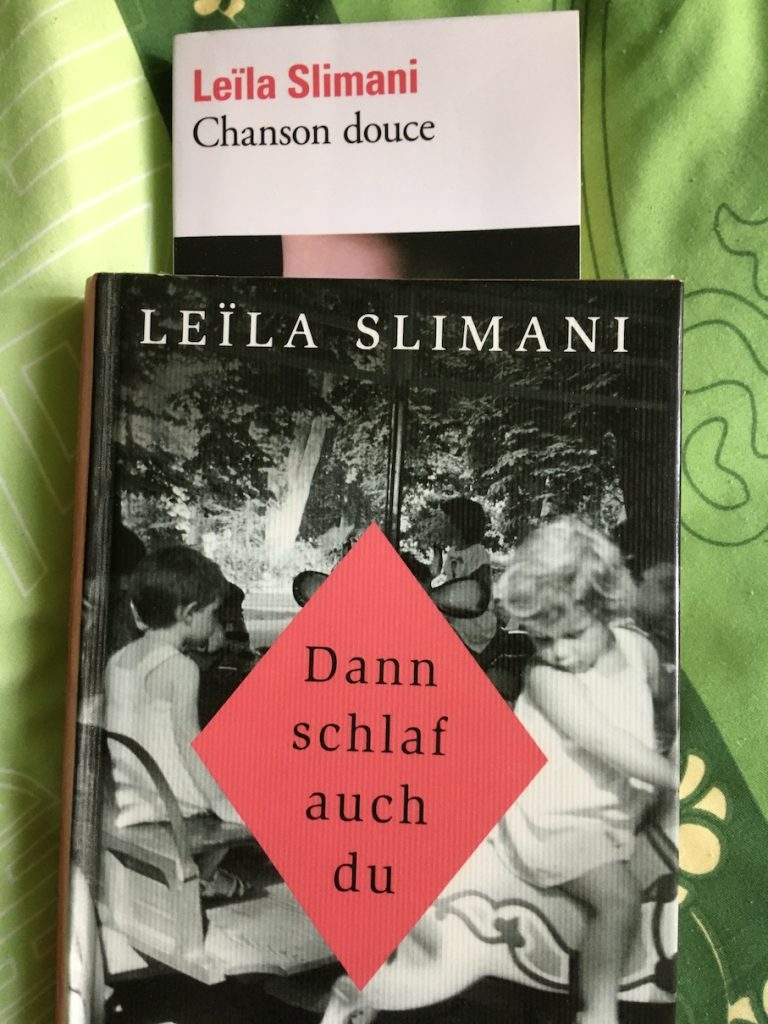

As mentioned here, Leïla Slimani’s Chanson douce (The Perfect Nanny in the US and Lullaby in the UK), in German translation as Dann schlaf auch du, did become available in my local library, and sooner than expected, and has now been read by me in the last day or so.

With a narrative that traverses the terrains of crime, suspense and underpinned by what could be interpreted as a social criticism of some aspects of modern family politics, and written in Slimani’s cool and precise style (I actually had the opportunity to browse the French original as I read the German edition), the novel makes for a rapid and compelling read. But, it is anything other than a comforting one. Not the butler, the nanny dun it – that much we know. When from the opening pages one is confronted with such a monstrous conclusion, the reader can not help but become engrossed in the quest to know the whole damned course of getting there.

Welcome into the hyper-stressed sphere of the restless Parisian middle class of young professionals; trying to organize careers and families, to keep up with …whoever are the French version of the Joneses, and ever alert to the social order and codes of their cohort. Such a couple are Paul and Myriam Massé, and they are much more of course, and Slimani develops them well; giving them contour – and contradiction. They interest me these thirty-somethings – juggling their ambitions with mounting insecurities seemingly at odds with their privileges. But with the family perfection of little girl Mila and baby boy Adam complete, Paul, who had found some favor and convenience in the one-partner-at-home model (in this case, the woman – surprise, surprise!), reluctantly acquiesces to the stressed and dissatisfied Myriam’s desire to return to her interrupted legal profession – so, the perfect nanny it must be; and it seems that Louise is just that.

I can well conjure a Paul and Myriam (perhaps I have known enough like them, or at least been informed of), but Louise remains to the very end a mystery to me, a mass of contradictions – her awkwardness in manner and speech; still, secretive, stubborn; a petite stature belying her vigor and strength; her plain, dated attire (peter pan collars we are told!) offset by cheap make-up – worn upon a face often described by the author as “moon face” or “doll face”. It irritated me that I was unable to form in my mind’s eye a more complete image of her. But perhaps that was the writer’s intent or at least an accident of the writer’s imagination: Dear reader, Slimani may be saying, think of Louise as an apparition blurred under the pale light of a full moon or some malleable figure with features painted upon china or plastic; garishly exact and without blemish. Neither are real, both an illusion. A mother’s worst nightmare.

For some readers, without proximity or at least awareness of the particular young, urban, professional milieu in which one is being drawn, the sociological aspects that may be read into the novel are somewhat elusive, and perhaps even inadequate as an explanation for the development of the plot; which I interpreted more as being psychologically driven. But deep seated norms are there to be extricated, and ultimately play an important role in the tragic human consequences. Parental choices made in modern societies are clearly complex – professional, financial, emotional considerations aplenty. But before that comes the choice to be a parent, and especially Myriam wonders at that; wonders at her own inadequacy and ineptitude – so conditioned is she in the absoluteness of the maternal role. Myriam thought she could have it all, failed to recognize the obstacles in her way, that cared not for her education, her abilities, saw only her sex. And wrong choices can be made, and most do not end with such a monstrous crime. (It should be said, Leïla Slimani based her novel on a 2012 murder in Manhattan; keeping some of the personal and class characteristics that were reported but transporting the situational to Paris.)

Expectations of a mutually beneficial alliance are negligible and the potential for conflict are high; for those (predominately) women who work in child care in some form or other – women like Louise and all those other nounous in the Parisian playgrounds – are often employed under precarious circumstances and for low wages. They may be immigrants or foreigners, students perhaps, and in this, Louise, as a white middle-aged French woman, differs; here, Slimani may have been deliberately making a character choice that defies the delusions of a society entrenched in its belief that all dangers come from without. Paul and Myriam could barely hide their satisfaction at not having to navigate the hurdles (as some of their friends must) brought into their home by a foreign custom or language.

I suppose, the reader may reasonably wonder whether they are being invited to consider whether those people a family like the Massés employ to care for their children, may well be doing so to the detriment of their own domestic circumstances (see the strands relating to Louise’s daughter), and whether their employers ever recognize as much. But, I think that would be a very hard indictment of Paul and Myriam; for it is not as though they are not interested nor curious, rather, Louise has developed an extraordinary repertoire by which to ward off unwanted inquiry, and for a time they only see – want to see – the positives of the arrangement, and are prepared to pardon the peculiarities and inconsistencies. It is also reasonable to ask; why, when Louise’s behavior and attitude increasingly exhibit signs of irregularities they do not respond firmly and in unison?

Interesting, I must say, are the alternating power dynamics. And, while they are particularly apparent in the relationship between Louise and Myriam, the fight for control is also remarkably potent in Louise’s relationship with the children, and especially Mila. And, it is not always the nanny who gets the upper hand. It seems to me, just as Louise knows how to play to Myriam’s feelings of inadequacy, guilt, jealousy – using the children and sometimes Paul as her tool – so too does Mila recognize in Louise a kindred spirit of sorts, there to be manipulated, possessing many of the petty, mean, childish qualities that she too has – it’s only that Mila is after all a child, and Louise is not.

As a reader, I found myself, almost unwillingly, swept along by the narrative, helpless to hinder that which had already happened, angry with the Massés for not heeding the warning signals, acting upon their intuition. (It’s all very well for one to say: with me, one such as Louise would have lasted not a week! – Oh, the lies we tell ourselves!) There one is, confined to being a bystander as Louise unravels, hurtling towards a breaking point, and taking a family with her. In fiction as in life, it is often the innocent, the children, who ultimately bear the consequences of lives broken.

With this in mind, I end with a traditional lullaby with lyrics that seem remarkably apt. (Presumably for merchandising reasons, the US publishers decided not to name the book as in the UK or as suggested by the German and the original French title.)

Hush-a-by baby on the tree top, When the wind blows the cradle will rock; When the bough breaks the cradle will fall, Down tumbles baby, cradle and all. 18th century traditional nursery rhyme