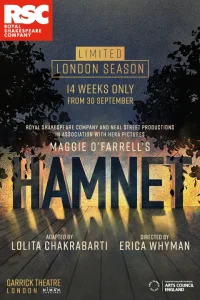

With Shakespeare on my mind of late, I take special note of the Royal Shakespeare Company production of Maggie O’Farrell’s best-selling novel Hamnet; recently premiered in Stratford and on its way to London in the autumn; and well reviewed, though both The Guardian and The New York Times, while mostly complimentary, suggest varying degrees of sentimentality. Oh, how I hate not being able to see these things!

Did anyone not like O’Farrell’s book? I dare say there were some. There are also some out there without a heart or, at least, to whom sentimentality is always an unreliable emotion: perhaps the theatrical production goes there, the book does not – unless one mistakes grief writ large for such.

I, then, was one of the most, or many, who enjoyed Hamnet – a lot really. I think it a fine work of the imagination; an example of one way through which a very good writer can grasp an idea that is, in itself, not absolutely original in terms of historical reading and scholarship but, by giving it an absolutely original emotional slant and a peculiar narrative twist, craft it into something quite ‘novel’.

Hamnet. Hamlet. What’s in a name? All or nothing at all? If one will, one can say “the name” is nigh on an anagram of “Hamnet” – or the other way around – save the duplicating of one pesky vowel – “the man”, who would have thunk it, is a perfect fit. But in good company with the Bard who, as with his contemporaneous creatives, all constantly inconsistent with their orthography; and Hamnet and Hamlet differ too by only one – this time a consonant; required only that it be only once lazily or hastily transcribed or mumbled quiet or loud. Still constant is the creeping duplicity. And duality – of people, of place – Hamnet or Judith, upon Avon or Thames.

Anne. Agnes. What’s in a name? And, when it is she who is the guiding light, the star of the ensemble here assembled? For so she is; it is filtered through the cloak of mystery in which the free-spirited Agnes is draped, that we encounter the spirit of the living Hamnet. Through Agnes’ eyes, Hamnet becomes more than just another boy-child lost to a past before history was made, barely more than an apparition; briefly there, then forever gone. Instead, his essence is captured and revealed; in death now channeled through a mother’s love and grief. But, it’s not just Hamnet that Agnes gifts us, but all the strangeness (and stagey-ness) of Elizabethan England, and the myriad of players cavorting in her fabled landscape – their talents, their habits, their secrets. Well be it that another wrote the words, and duly credited, but Agnes it is who provides the rhythm along with which the story beats and soars.

And the man? What of that other not named? He, the conjurer of words and stories destined for an immortality of sorts? A man with two lives, or as many lives as his quill and posterity has granted. Here, though, just a mortal husband and father. For this story, Agnes’ version is enough.

A longer interview with Maggie O’Farrell with The Observer is here on the The Guardian website.