The British Government line for why they have maintained a relatively passive role in deciding the fate of the stolen Parthenon Marbles (I’ve always said “Elgin Marbles” – me thinks that ain’t exactly p.c. these days!) has always rested strongly on the reasoning that the spectacular artifacts were removed from the Acropolis and brought into the UK by Lord Elgin in the 19th century – that is, it was a historically private initiative, unhindered by the Greek officialdom and following international and diplomatic protocols in place at the time, and over which the Government had little to no influence then and presumably no legal liability now. In the light of this, a report in The Guardian a couple of days ago about research suggesting that the foreign secretary of the day, Viscount Castlereagh, was, in fact, very much involved in the initiative and in facilitating the import of the marbles, offers an interesting new angle in what must be one of the longest and most famous disputes concerning stolen antiquities.

The publication of these findings comes at a particularly timely moment it has to be said; coming on the back of a renewed campaign by the Greek government, partly inspired by the sudden change of stance by The Times at the beginning of the year and public opinion in the UK in general, and the British Museum showing signs of a willingness to explore compromise solutions (talk for instance of a so-called “Parthenon Partnership” and a new Parthenon Project.).

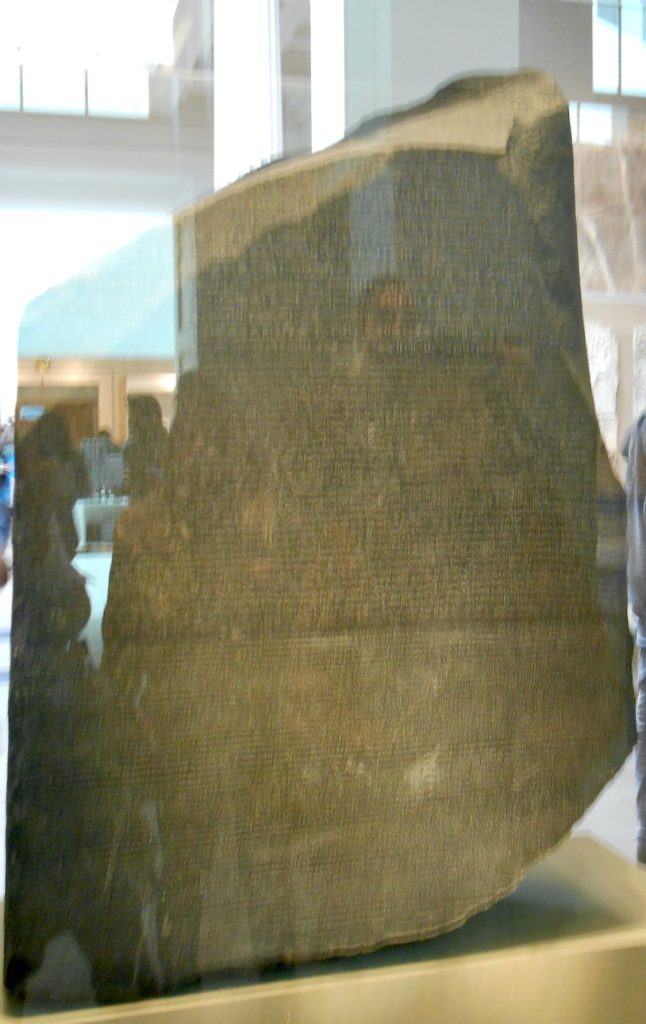

Staying at the British Museum: There is the matter of the Rosetta Stone – famously, the engraved artifact with which Jean-François Champollion went about his decoding of the hitherto puzzle of hieroglyphs. The physical object of course is one thing, but just as important, perhaps, is the way in which the astounding work of Champollion and others shone new light upon the richness of ancient Egyptian civilisation – their society, customs and belief systems. In recognition of Champollion’s scholarship there is a major exhibition Hieroglyphs: unlocking ancient Egypt at the British Museum through to 19 February 2023 (and I note an extended blog piece by the curator, Ilona Regulski). And another at the Louvre satellite in Lens, Champollion: La voie des hiéroglyphes (the webpage is only in French, but the objects can be looked at) until 16 January.

Not quite as loudly as Greece, but Egypt too has called for the return of their “lost” heritage over the years. The loudest, though no longer in a governmental role, has been the renowned (and publicity savvy) Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass who regularly pleads for the Stone’s restitution (as he likewise does for Nefertiti’s return from Berlin). In some ways this case is more complicated, in that the Rosetta Stone was amongst the many artifacts that were handed over to the British in a formal agreement as a result of the capitulation of Napoleon’s army in Egypt. Though one could conclude: Okay, so the French excavated, confiscated – maybe nicked – all this stuff and the Brits just help themselves to the spoils? What!

I admit to being a convert tending more to the ‘return’ side of the argument. Way back whenever I was amongst those (many, I believe) interested observers of the mounting controversies who just sort of presumed western museums (located in democratic countries, in more moderate climatic regions – both factors remain good – but not defining – arguments) had the space, financial and technical resources, expertise to best ensure the preservation of some of the treasures of world civilization. Unfortunately, it has to be said, many of these institutions (mostly led by an older generation and with the tacit support of their governments) have over decades been too reluctant to seriously engage with the claims made by the nations and peoples from whence many cultural objects have originated and, even when, have confronted the claimants with a sometimes patronizing, often impatient and nearly always paternalistic attitude. Ultimately, I think, one has to be prepared to accept the good will and intentions of those who seek restitution of their property and their right to make decisions that they deem in the best interest of the preservation and continuity of their cultural heritage. There are enough examples of how that may happen – with partnerships, exchanges, even new museums.

It seems, then, after years of bulwark tactics, the British Museum may be finally progressing towards an inclusive and respectful course of cultural and intellectual exchange. And it is not alone, for younger generations are taking on leadership roles at many other of the world’s great institutions; generations that are more diverse and with broader cultural visions. This, I think, is good news (something at a premium these days!) for the many nations that are reorganizing their cultural legacy in a post-colonial world.