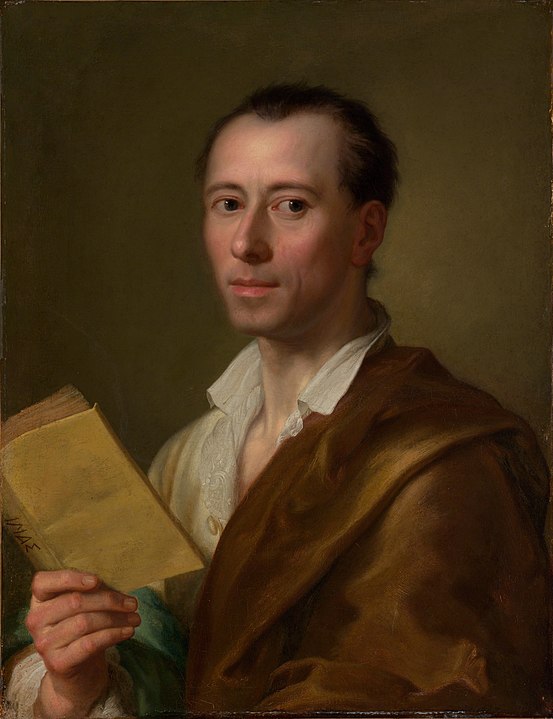

I intermittently catch the BBC Radio 3 cultural program “The Essay”, and are often surprised by its content, but it actually took an article in the Frankfurter Allgemeine to alert me to these episodes (still available as I write on Sounds) about the circumstances surrounding the 1768 murder in Trieste of Johann Joachim Winckelmann – considered to be one of the first practitioners of what we would now call art history and archaeology. I say that, but it is more. The cultural historian, Seán Williams, is also telling the wider narrative of a celebrity “gay life” (and death) during the Enlightenment – what could be done and what not, where and with whom – and how it has been interpreted in the afterlife, both in respect to Winckelmann but in the myth building around cultural icons.

Winckelmann interests me. He turns up in this blog post, in which I touch upon newer research and reconstruction methods in polychromy that supports the view that the artifacts of antiquity were very colorful indeed; running counter to the monochromatic orthodoxy which had first arisen during the Renaissance but the certainty about which began to crack during the Neoclassical period of the 18th century – a cultural movement and time of which Winckelmann was a “mover and shaker”. Under nearer scrutiny, traces of pigment were being observed for the first time on objects, and even Winckelmann (albeit belatedly) changed his stance. But, by the 20th century, and for whatever reason – racism, the aesthetic of fascism it has been suggested – all the scholarship and practical methodology of the 18th century was being rejected in favor of the marble white, purity narrative, and prevails still in the contemporary consciousness. The latter is hardly surprising when the artifacts and fragments on display in the museums of the world mostly have very little pigment remaining, and labels are not always explanatory.

As I say, Johann Joachim Winckelmann interested me anyway, but Sean Williams’ radio essay has added an extra dimension. (Here, in his own words, a short accompanying text.)