The very opposite of angelic this ‘little’ England at the end of the Elizabethan period, as it hurtled towards the headless state – symbolically and actually with bloody precision – that it was to become in the 17th century – or as such it was seen from a Continental perspective: intemperate, delusional, diabolical this land – a veritable playground for the devil and his helpers.

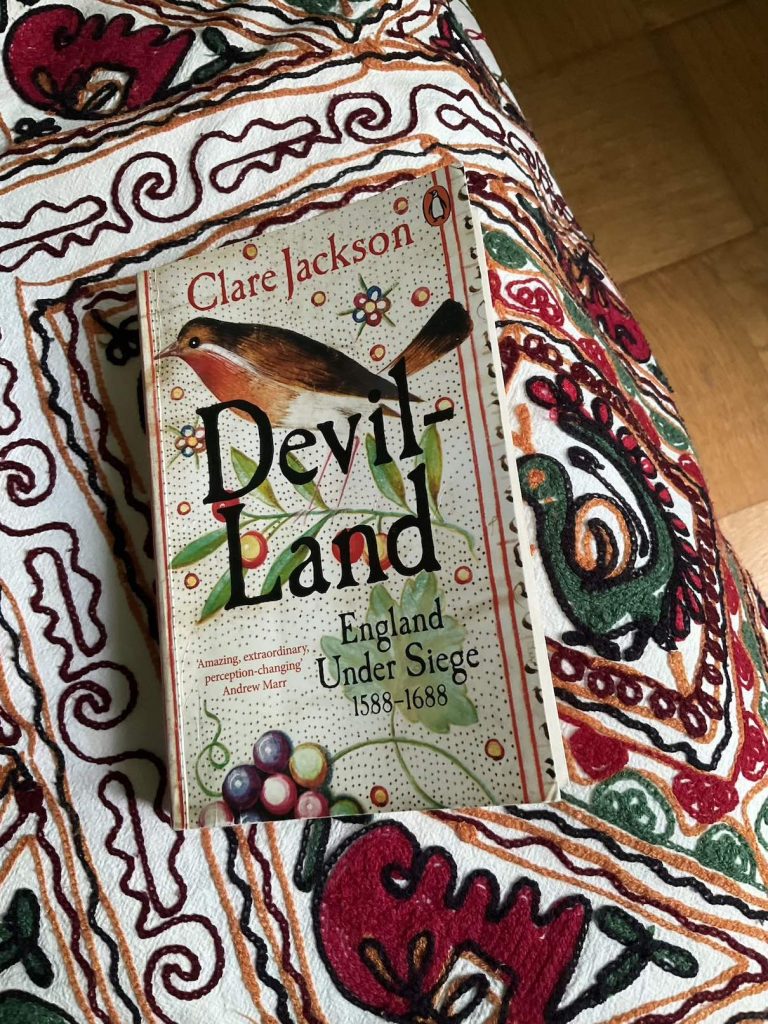

And it is with this particular slant that Clare Jackson shades her terrific history of that turbulent period of Stuart dynastic power grabs and downfalls, civil wars, religious fervor and parliamentarian purges. Devil-Land: England Under Siege, 1588-1688 (Penguin, 2021) is neither a quick nor easy read, it has taken me ‘forever’ – or a few weeks at least; it is a book that demands concentration, but ultimately one is rewarded for the effort; for it is an endlessly thought provoking book – a sweeping, wonderfully written immersion into a violent, volatile epoch defined by all the intricate webs of subterfuge being spun within and without the borders of a ‘middling’ kingdom, a still only imagined ‘great’ Britain, and the reciprocated meddlings by the powerful absolute monarchies on the Continent. And always amongst each other – nobles, courtiers, clergy, diplomats, pamphleteers – intrigants, disputants are they all, having their say and rarely getting their way. One day’s friend is the next day’s foe. Today’s loyal subject is tomorrow’s rabble rousing republican. Lines of succession, familial loyalties and matters of fertility mean everything or nothing. Words, written or spoken out loud, vulgar or lyrical: long-winded, idle ‘talk’ exposed, rightly or wrongly, to be seditious; hushed gossip becoming loud and with conspiratorial intent – the next plot brewing. Crowns and heads are lost and crowns at least restored, in-between all means of civil and uncivil strife, religious and sectarian conflicts contested with zealotry and culminating with a bloodless coup – okay, Glorious Revolution has more oomph – and the reign of William of Orange.

It is any wonder the movers and shakers across the channel – above all, Habsburgs and Bourbons strewn all over the Continent – were at first bemused and then (literally) up in arms – at the antics of those intemperate ratbags on the other side of those narrow, treacherous waters to be crossed at one’s own peril; channeling in its capriciousness that very folk. Though, it must be emphasized, things weren’t exactly going down well in their own backyard either! To call foul (“REGICIDE!”) on the public execution of Charles I was a bit much when half of Europe lay in Schutt und Asche in the aftermath of the Thirty Years War.

It is left to be said, with the beginning of the 18th century the House of Stuart would be succeeded in an orderly, that is, a predetermined fashion (lessons had been learnt!), by that of Hanover, and the chaos of the ancient English parliamentary system and flirtations with republicanism gave way to one anchored in law and reconstituted under a united Great Britain, which, on the back of brutal colonial expansionism, quickly rose to become a globally dominating power. The devil may still have been at work on the island, but a devil to be taken seriously and his objectives clear. Besides, it was on the other side of the channel on a vast continent struggling with modernity, variations of – and alternatives to – absolutism and the rise of nationalism fervour, that his focus was to shift during the next centuries. Therein, of course, lay another story.

As a reader, however enmeshed I was in this tumultuous past, the contemporary had a way of insinuating itself upon my reception – the ghosts of a ‘glorious’ past tainted by nostalgia and nationalism, and exemplified by the hubris of Brexit; controversial and unsolved questions of devolution and more generally nationhood and identity (see, for instance, Scotland’s striving for independence, a non-functioning Stormont in Northern Ireland); the role of the monarchy (it just has to be Charles III doesn’t it!); the deficits of the Westminster parliamentary system (prorogation, serial PMs, etc.); the limits governments can place on individual freedoms (during the plague of 1665, restrictions included the closing down of taverns and play-houses – sounds familiar?). But these very here and now intrusions that flutter in and out during the long reading of Devil-Land – some of which I suspect were deliberately planted by Jackson – help to illustrate and focus the big picture on the tensions created in the relations between England and Europe, the personalities at its core, the interests being served, and how the parties could be now, as then, so near yet so far.

continue reading …