From my last post, The New York Times has now published an article on Christie’s forthcoming auction that will include three works from Vincent van Gogh; one of which is the Meules de Blé of which I wrote, stolen by the Nazis and only now returning to the public arena.

Fortuitously, the NYT linked to The Art Newspaper and the Van Gogh expert, Martin Bailey’s blog piece which provides relevant and well-informed background to the van Gogh works being offered. My interest is now ignited by Jeune Homme au Bleuet (1890) – The “Young Man with a Cornflower”, has its own particular narrative through place and time, that had “him” as a “her” – Jeune fille au bluet (the mad girl in Zola’s ‘Germinal’) – when it all began …

And when did it begin? Well, according to Virginia Woolf “… on or about December 1910 […is when human character changed]“. And, Van Gogh’s girl/boy was right there at the legendary Autumn 1910 exhibition at the Grafton Gallery in London, Manet and the Post-Impressionists, curated by Roger Fry, about which Woolf spoke – where more than a word was created that defined a direction, but the visual artistic representation displayed that signaled an end and a beginning. And by the bye inflamed the establishment to various degrees of rage! In 2010, The Burlington Magazine celebrating the centenary of the show, included an interesting piece about the original exhibition catalogue.

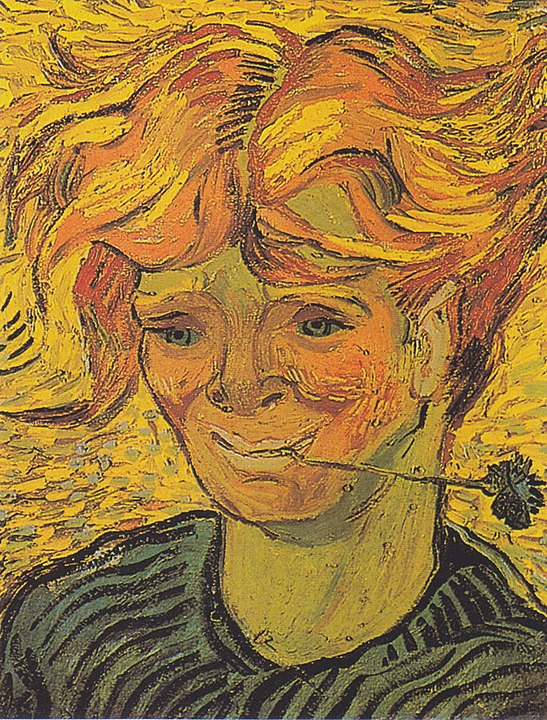

Though I am not adverse to haystacks, nor to cypress and olive trees, this figure I do find captivating. Unlike the stolen haystacks, an image of Jeune Homme au bleuet is in Wikipedia. It’s not at all a good reproduction so I post it here reluctantly – the colors quite wrong; the cornflower is blue, as is the blouse, the hair copper-red, the face pink and lips paler as if masked, the eyes emerald – so I refer you again to the very good Christie’s site; for both the much better visual reproduction and, again, an excellent lot essay.

The gender ambiguity is one aspect, but in these days of fluidity (making ambiguity somewhat obsolete!) I am more taken by the almost carnivalesque nature of the portraiture; reminding me of Pippi Longstocking illustrations and depictions elsewhere – the essay description of “mischievous ragamuffin” seems more than apt.