On hearing last week that a digitized version of Virginia Woolf’s personal copy of her first novel The Voyage Out is now freely available, I read around the many reports including at the BBC (a Radio 4 news report had been my first source), and linked to a timely article by Mark Byron from the University of Sydney (where the original resides) in The Conversation. This article I have now republished here.

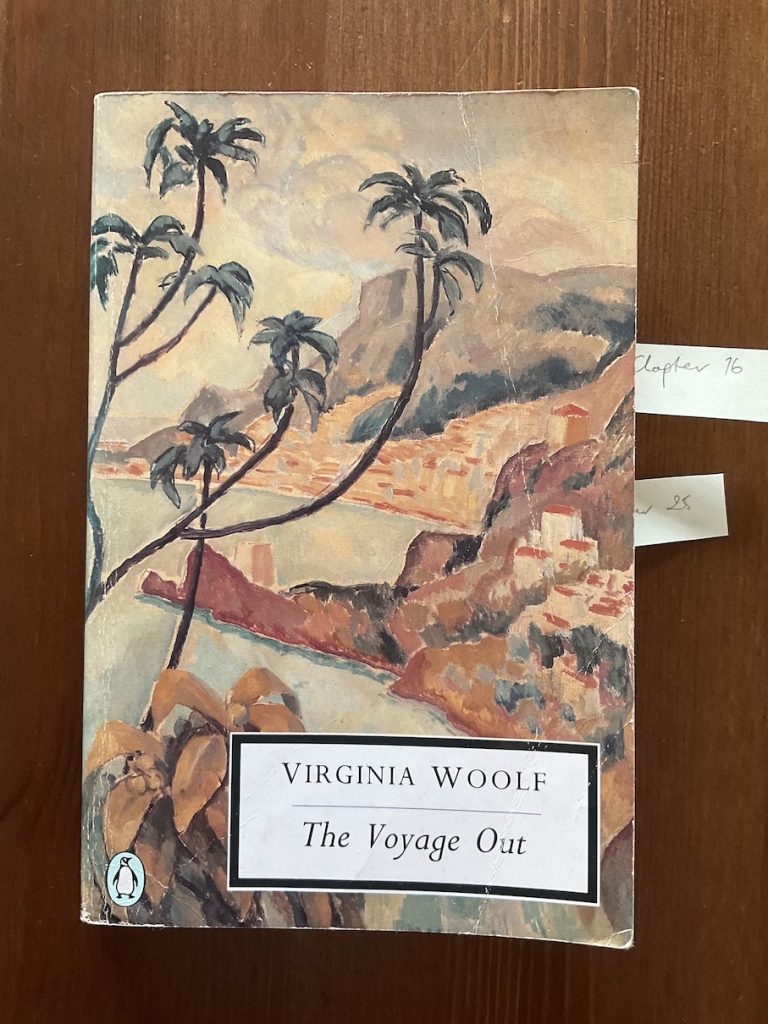

Here now is the link to the University of Sydney library – with a well formatted web version of Woolf’s book; also available for download as pdf. The accompanying description alerts one to Woolf’s revisions in Chapter 16 (pp.249-267 [web-tool/pdf 262-284] with typed paste-ins on pages 254 and 256) and Chapter 25 (pp.398-432 [411-445] with a number of deletions) in preparation for the book’s US publication in 1920.

A glance to her diary is informative in this regard. Virginia Woolf writes on 28th November 1919, that two parties are interested in both The Voyage Out and Night and Day and their publication appears likely, and a footnote confirms that to be the case – with George H. Doran of New York becoming Woolf’s first American publisher [see The Diary of Virginia Woolf Volume 1]. Then, the on 4th February 1920 she writes:

The morning from 12 to 1 I spend reading the Voyage Out. I’ve not read it since July 1913. And if you ask me what I think I must reply that I don’t know – such a harlequinade as it it is – such an assortment of patches – here simple & severe – here frivolous & shallow – here like God’s truth – here strong & free flowing as I could wish. What to make of it, Heaven knows. The failures are ghastly enough to make my cheeks burn – & then a turn of the sentence, a direct look ahead of me, makes them burn in a different way. On the whole i like the womans mind considerably. How gallantly she takes her fences – & my word, what a gift for pen & ink! I can do little to amend; & must go down to posterity the author of cheap witticisms, smart satires & even, I find, vulgarisms – crudities rather – that will never cease to rankle in the grave. Yet I see how people prefer it to N. & D. – I don’t say admire it more, but find it a more gallant & inspiriting spectacle.

The Diary of Virginia Woolf Volume Two (1920-1924)

Woolf’s tone in the private space of her diary suggests, irrespective of the blush, some pride in her younger self. Remember, as “Melymbrosia”, her book first started taking form as early as 1907, and remember, too, as Virginia surely would have, her severe mental illness during many of those preceding years. That Virginia must be respected.

At the Internet Archive is a copy of the Doran first edition, and it appears to me those corrections suggested by Woolf’s annotations in this newly ‘found’ treasure were adopted only in part – the paragraphs she suggests in Chapter 16 were indeed included (quite how, and what if anything was omitted only a more thorough look on my part will reveal) but those in Chapter 25 that she (?) suggested be deleted seem to remain in full in the US publication. This latter is particularly interesting; I could imagine Woolf mulling over whether Rachel’s feverish state may be interpreted as something close to her own mental agonies over the years. Leaving aside the veracity of my hypothesis and Woolf’s intentions, I have always found Rachel’s torment through those days and nights extraordinarily vivid. It must have been lived. Virginia lived through it. Rachel did not.

Virginia’s book has made quite a ‘voyage’ of its own. Presumably beginning in a room of her own (though the writing and editing of her first novel predates her actually having a room of her own – that did not come her way until 1919) in London and/or Sussex, onwards to her literary estate and its executors, somehow turning up in a bookshop in Lewes from whence it was sold in 1976 – were they mad, or was this simply a failure to predict the market potential? – to an Antipodean university, whereupon it was promptly (?) lost into the cavernous depths of the science section – were THEY mad? An ABC report explains the chain of events up until the book’s reemergence in 2021. To which we can only say: god bless literate, curious and alert Metadata Service Officers!