“Caste – the Lies that Divide Us” by Isabel Wilkerson

That is the thing with definitions, be they of word, phrase or more complex description; beyond the essential vocabulary and grammatical rectitude, precision is rarely absolute and very often determined by context; imbedded in society, geography and time.

One such word that provides an interesting example is ‘caste’. As an Anne with an ‘e’ like she from Green Gables, and having always been uncompromisingly for its quiet but firm closing presence both in word and speech, I have blithely accepted caste so spelt to have just one definition, and that firmly rooted on the Indian sub-continent and descriptive of the system of social stratification that has existed there since ancient times. Now, of course, it turns out to be infinitely more complex than that, even when specific to Indian society, but the etymological route from the Latin castus ‘to be cut-off, separated’ through to the Portuguese casta meaning ‘breed or race’ and adopted by – and complicated by – the British Raj is clear. That the very ordinary and malleable word cast is strongly associated is equally so (though a matter to which I have not previously given thought!) – always somehow to do with throwing together, throwing away – a troupe of players (cast of characters); iron (cast-iron); a fishing line; a dice (literally, and metaphorically as in iacta alea est; the die is cast) And then there are all those who are cast out, away; who are downcast, typecast.

Not wishing to cast aspersions (to stay with my train of thought!) on Oprah Winfrey, but when a tome comes my way emblazoned with “Magnificent. Profound. Eye-opening. Sobering. Hopeful” my antennae begin to twitch nervously. Be that as it may, I said here that I would read Isabel Wilkerson’s 2020 book Caste: The Lies That Divide Us (as my copy is titled), and I have, and so give here a few of my thoughts.

Only now after reading Caste and upon reflection, has it occurred to me that Wilkerson also used that terminology in her 2010 bestseller The Warmth of Other Suns; though, I think, sparsely and without particular emphasis, nor can I remember that she specifically explained her choice of vocabulary. Of course, I may be wrong on this, but on any account it is obviously a means of framing race that she has mulled over for a relatively long period, and one that she thought needed refining and deserving of its very own book. This I am not so sure of; I would even contend it even muddies the waters.

And, this is not to say that I didn’t find Caste an interesting enough read; for despite the objections I have – and there are a few (or maybe many!) – and however dissatisfied I was in the conclusions drawn by the author, Wilkerson is a very good writer and journalist, who can weave the factual with anecdotal to present the narrative that she very well wants to tell, and in the interests of a firmly held point of view and, furthermore, in an accessible style well suited for popular consumption. Perhaps here lies the crux of my criticism – the author, it seems to me, was so intent on telling her one version, that she has not even attempted to identify faults in her argument or to consider whether her reasoning may be inadequate or does not lend itself to generalization (across vast expanses of time and place). And as colorful as they sometimes may be, her more personal micro-narratives with typical micro-aggressions at their core have a tendency to aggravate. Now I can’t be sure, but who hasn’t been pushed, shoved, insulted, etc., by some dude on a plane (though I’ve never had the luxury of first class!), or felt out of place or ignored in a crowd, and my irritation hasn’t been lessened by reflecting upon interviews that Wilkerson has given in the last year or so in which the same anecdotes are rattled off. That’s okay, but one has to wonder what she thinks they add to her argument, other than presumably offering up herself as an example of the subordinate caste. As a highly successful, Black American woman of renown, fair or not, that premise rests on shaky ground. When I say this, I don’t wish to diminish the sensitivities of those who are subjected to or slighted by everyday racism, or sexism, or both, it is just that I think when putting forward an argument, or espousing a theory, sometimes it is better to stand back – a little less subjectivity is more.

On a fundamental level, I have to say I struggled with Wilkerson’s ‘update’ of an ancient caste model to expound her own “eight pillar” theoretical framework, one in which racial discrimination is inherent, and racial purity and allocation of labor constrained within each hierarchy is aspired to. And, to then whittle this down to the existence of a rigid three tier caste system in the United States; one in which the white majority in all their, presumably homogeneous, glory reigns on high, a Hispanic and Asian middle struggles to ascend – whereby the very possibility of doing so is antithetical to a caste construction, and a Black minority, relegated (and by virtue of their skin color alone) to the lower caste. The result is, in my opinion, a much too simple reading of the dynamics at play in a modern society driven by capitalism; Wilkerson’s absolute decoupling of race from capital fatally ignores the latter as the ultimate “pillar” (to use her language) in supporting – perpetuating – racial inequities in the United States.

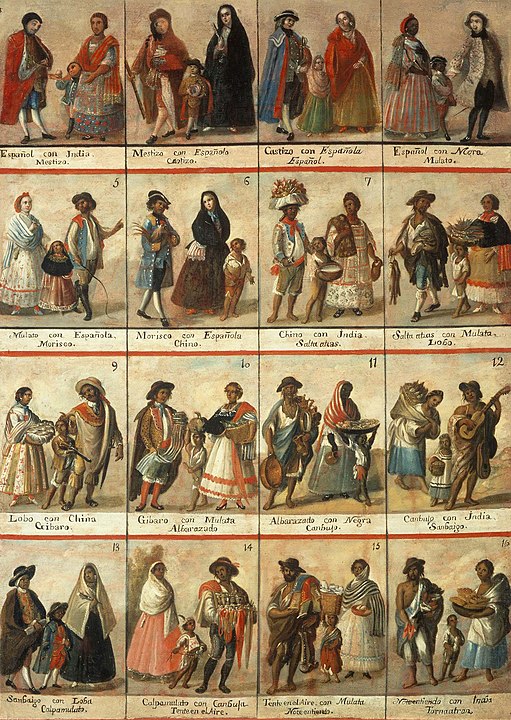

Wilkerson’s attempt to, shall we say, internationalize her thesis with her chosen vocabulary and comparisons – India and Nazi Germany (1933-1945!) – strikes me as a narrative device, as a professional writer’s search for an original angle. Understandable to be sure, for books on ‘race issues’ aren’t exactly underrepresented in these days, but ultimately her perspective is peculiarly insular, inward looking. One looks (out!) in vain for some discussion of how societies are (or have been) organized on the African continent, or how some Latin American countries have developed from not dissimilar beginnings. Tidying Brazil up into a neat caste system would certainly be a feat! For more on this I really suggest Hazel Carby’s essay for the London Review of Books (limited access unfortunately), that I mentioned previously – and is the reason I find myself sitting here writing this! Carby’s piece explores the shortcomings of an argument that fails to take into account the complex interactions that develop between races (including those indigenous) as they move through geographies, and is not interested in a broader, transnational approach.

Firstly, though – India. Again, caste is an ancient concept embedded in the long history of Indian civilization – with or without the precise terminology – one that has evolved over thousands of years in the murky swamps and swirling mists of mythology, religion(s), empires, invasions, migrations, colonial subjugation, independence. I am with Martin Luther King, Jr. and his first instinct (which Wilkerson admits to) which was to disavow an association between the Dalit experience and that of the African-Americans. It was a far-fetched comparison then and it remains so now, but Wilkerson imagines (it seems to me) that King came to identify a commonality of purpose. In fact, there is little evidence to suggest that after this one trip to India, whilst impressed by the non-violent struggle (for independence) and how this could work towards breaking down the barriers and improving the lot of the lower castes, that King further pursued or had any interest in caste as an innate concept applicable to race relations in the United States.

That the Indian caste system has its roots in occupation rather than physiognomy and that it is intrinsically bound to religious tradition, neither of which are defining characteristics of racism in the United States, would to me from the outset disqualify it as a good comparative tool, as would the many and varied subsets that exist within each caste, even the lowest (Dalit). Wilkerson’s model does not call for sub-castes. The contemporary Dalit experience is not expounded upon, nor the extraordinarily complicated overall interaction of caste and class in Indian society and politics – as an example, a term like “Other Backward Class” suggests that here one is in the midst of another social ordering system.

And, the German Nazis? Again, to equate that singular period that resulted in the Holocaust and the murder of millions of Jews and the dispersion of as many more to the farthest reaches, and all within a dozen or so years, with the racial discrimination and inequalities of the contemporary United States, forged as they were out of a violent past: the trans-Atlantic slave trade at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the founding of a nation, the human cost of the economic choices made, the divided nation that ensured, the failure of reconciliation and repatriation, and the immense price paid through the twentieth and into the now, is spurious to say the least. I must say I am mind-boggled that so many (book) critics in the States let all this pass. That the Nazis looked towards the segregation and miscegenation laws of the South when defining their own “blood laws” may very well be so, but I do suggest that they hardly needed inspiration in this respect – there was enough fodder nearer to home in the long history of ghettoization in European cities and the pogroms of the Russian Empire in the late 19th and early 20th century. Granted, race and eugenic theories abounded in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century, but these ideas whilst fermenting in the elite universities and amongst the intelligentsia and being transported into the state houses and the board rooms, were mostly imported from prevailing European thought at the time that attempted to counter Darwin’s monogenesis theory with various versions of polygenism – for instance; Haeckel, Galton (Darwin’s cousin who invented the word ‘eugenics’), Agassiz.

Because it is a matter of topical interest in Germany today, it is worth here saying that during the Herero and Nama Uprising of 1904 to 1908, in what was called German South-West Africa (now Namibia) and that left tens of thousands dead and the population decimated, many of those fleeing the war were captured and put in so-called “concentration camps” in which they were brutalized – not only through slave labor, but by torture and execution and by being subjected to bizarre medical experimentation. This all thirty odd years before the rise of National Socialism in Germany and probably not inspired by either the plantations of the antebellum American South or the failed Black Codes during the Reconstruction era, but rather as a continuation of other brutal colonial regimes on the African continent – the Belgians in the Congo, the British and the French most everywhere else. In other words, the Nazis in their barbarous campaign against the Jews (and other marginalised peoples like the Sinti and Roma) did not have to look across the Atlantic for inspiration, there was enough to be found amongst their fathers. (This, all a matter deserving of more attention; intersecting as it does many issues that interest me, I intend to return to it in more detail – but not before I am sufficiently up to speed myself.)

I was surprised that the perversion known as social Darwinism, whereby society is modelled on and described in the language of “natural selection” and evolution, does not come to the fore in the book; after all, it is under this mantel that the Republicans fled, taking much of the North with them, and which was adopted as a central argument for the abandonment of Reconstruction – no longer a process of reconciliation and reinvention but reconsidered as a wrong minded experiment in governmental intervention in the natural order of things and forcing of social hierarchies rather than allowing them to evolve – and became the theoretical underpinning for the extreme disparities of wealth and the class frictions and labour unrest of the Gilded Age. And, into the 20th century we know where all that led. Wilkerson seems to think it of little consequence to her comparative discourse that, whilst the Nazis were intent on eradicating the Jewish population, slaves in the antebellum South, though systematically dehumanised and maltreated, were ultimately human capital inextricable from the economic model of the plantation and, in the century and more that followed, African-Americans remained a factor in the success of American capitalism. Two very different forms of oppression, with different objectives and outcomes, I would contend.

But, Wilkerson, in focusing her argument on the comparative is able to avoid the messy stuff; that is, of talking about race in relation to the distribution of wealth, class and labor. Her insistence that caste is an invisible agent (think, skeleton) to the perpetuation of racial stereotyping, that its precepts ignore wealth, education, success, confines her focus to a particular segment of the Black population; one that can afford to differentiate between the subtle and the blatant, the inherent and the learned. I can only conclude that in the end Wilkerson is writing as a representative of that class and for that class – and for Oprah Winfrey, whose ecstatic praise for her book is that of a mega-rich, mega-famous Black woman famously slighted by every day racism in a Swiss boutique (I remember this!). What all this caste rigmarole tells us about the radically disproportionate amount of Black people who have suffered physically, emotionally and economically in the pandemic; who are employed in lousy jobs or multiple jobs; are incarcerated; are without health care; are on benefits, I don’t know. The skeleton Wilkerson took as her metaphor for caste certainly was not that of any people such as these.

My verdict sounds harsh, so I would like to finish by saying that I liked Isabel Wilkerson’s previous book, The Warmth of Other Suns, so very much more. As I said previously, I didn’t pay particular attention to her choice of vocabulary, so immersed that I was in the intermingled narratives of her chosen subjects as they moved out of the Jim Crow South during the Great Migration in the early to mid 20th century. Wilkerson beautifully describes the larger nation and society that they discovered on their (physical and emotional) journeys; offering opportunities and rewards not to be realised in the places of their birth, but not without hardship, and confirming deep-seated prejudices and inequalities – many of which exist still. I cant help but think, that it is with such real life stories – reported up close and tightly structured to a whole – that Wilkerson’s considerable talents lie. In my opinion, her particular narrative style does not lend itself to dense theoretical and historical investigation – there are enough academics out there for such, most of whom could not write with her verve but would be better equipped to coherently develop a thesis – or even recognise its wrongness.