“Passing” by Nella Larsen

With the success of Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half last year (which I wrote about here), it could hardly surprise that Nella Larsen’s 1929 novel would resurface and be talked about again, and therefore appropriate that Bennett be at the centre of this T Book Club event.

And here is Bennett’s accompanying essay, which exacerbates on some of the topics that arose in the conversation, and introduces new ones.

Not just about Passing, Brit Bennett also speaks on the person Nella Larsen, beyond the writer, and the complicated paths her life took. After years of obscurity – the NYT famously overlooked her death in 1964 – Larson was rediscovered by feminist academics during the 1970s, and given place amongst the (mostly male) Harlem Renaissance. Interest in Larsen has been sustained through the ensuing years, including what Darryl Pinckney calls a definitive biography in 2006 by George Hutchinson, which he reviewed at The Nation upon publication. I mention the biographical information (via Pinckney and Wiki) only because, it seems to me, the oddness – or, the inconsistencies – of Larson’s life are not dissimilar to those to be discerned in the novel.

But, that is the thing with the unreliable; it titillates, seduces and ultimately leaves –has to leave – some things unresolved. And so it is with the voice of Nella Larsen speaking to us through Irene Redfield. I recall Brit Bennett mentioning Irene’s world to be a rare example of a historical depiction of middle-class Black America, and it is this term “middle-class” that perplexes me; but that is generally so, for its definition is very dependent upon context – in place and in time – and neither being American nor clear on the historical demographics of New York, I may have a different understanding of a socio-economic scale. And so I am left to be wowed at what a middle-class that must have been in Harlem in the 1920s! The Redfieds for instance: doctor, wife; juggling social calendar and committees; entertaining and being entertained by literary luminaries; trips abroad, private schools; upstairs, downstairs; separate bedrooms (which I mention because of the spatial factor – what it says about the relationship between Irene and Brian is another matter!); housemaid, cook. Many of these are attributes I find difficult to relate to the middle-classes – somewhat too uppity, to my mind! Is the Harlem of her novel that in which Nella Larsen lived, the society to which she aspired? Or has she over-imagined both?

Passing is quite a short novel; the language and form unfussy but the descriptions often vivid, the narrative is told in the third person from the perspective of Irene, and within three clearly defined parts – firstly as a reflection from a present point of view back two years to Irene’s chance meeting with Clare Kendry, and then into that present and Clare’s renewed insinuation into her life and the mayhem that wreaks upon Irene’s hitherto ordered existence, and culminating with a tragic, and ambiguous, finale. I liked Irene and Clare except when I didn’t, had sympathy with them except when I didn’t. Their intense preoccupation with getting under each other’s skin ultimately gets under the reader’s skin as well – sensual that may be, but also full of resentment and regret. And irrespective of any inconsistencies, I was very interested in the deliberate insertion of class into the race dynamic, adding a complexity beyond a purely black and white argument. Clare, had not only passed racially, she had also passed from her precarious mixed-race childhood, impoverished and on the fringes, to a life of material privilege. And Irene’s punctilious attention to the conventions of class, was exposed in all its insincerity, and to be as much a betrayal of her race as Clare’s more blatant act.

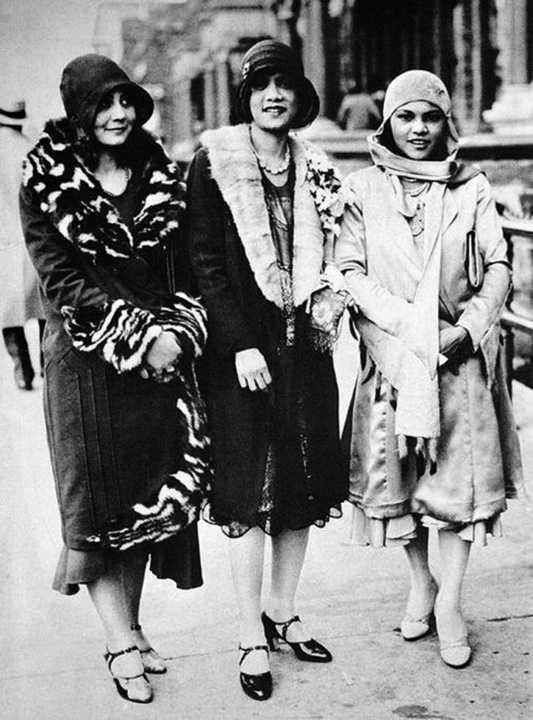

On reading both Larsen’s novel and Brit Bennett’s, I must say I couldn’t help but be impressed at the sheer nerve and hard work required by their characters to pull off this act of deception, this thing called “passing” – and not just fleetingly as Irene does should the situation arise, but for the long haul and with all its consequences, as it is for her antagonist Clare, and for Stella in Bennett’s novel. And the consequences will be different and determined to some extent by the times in which they lived; for Clare at the beginning of the twentieth century it could only end in tragedy, and for Stella, at the other end of that same century, however complicated, there is still a life for her to live.

Finally, I make mention of Rebecca Hall’s directorial debut filming of Passing, which premiered at Sundance in January and is to be shown on Netflix (another pandemic casualty!) later this year. Filmed in monochrome and with an impressive cast, irrespective of some mixed reviews, I look forward to seeing it. For the talented Rebecca Hall; very personal, and a labour of love.

30th March: As a post-script I should say I am coming to the end of reading Isabel Wilkerson’s 2010 study of the Great Migration, The Warmth of Other Suns; an engrossing historical narrative, constructed around real lives and experiences, of the movement of Black Southerners into the North and West during the 20th century. In the context of the two novels I have spoken of above, I remember well one anecdote concerning a family’s journey West, and that even in El Paso and to all intents and purposes almost beyond the reach of Jim Crow, passing was the only option to get motel accommodation, and the family having to resort to extraordinary measures to smuggle in one little boy who was a lot darker than the rest of the family. Some of that nuance of class that I discern to be a defining characteristic of Larsen’s novel is also there in Wilkerson’s real life account; new arrivals out of the South were not only still subjected to racism (not just from long time residents but also from recently arrived European immigrants), albeit of a brand that was unfamiliar, varied in degrees of aggression and often delivered with a subtlety unknown in their previous experience, but had to often contend with social stigmatisation and the pecking order of the existing Black communities.