Oh, and war!…Just a few of the words that come to mind of a much darker time four hundred odd years ago (1618-1648) that puts this year of ours into perspective. One could add: torture, execution, butchery, disease…You surely get the picture.

Well I do…having finished reading Daniel Kehlmann’s latest work, Tyll, (mentioned here upon its recent publication in English, though I read in German so I can not speak on the translation) which powerfully describes the devastation visited upon a continent and its peoples – brutalised as they were through all the above said … I can’t think that it would have occurred to Kehlmann just how prescient his novel would be. Not in that the grotesqueness of a pre-modern era (and the literary form chosen) is so relatable, rather that the grotesqueness told as it is with a picaresque slant and the mocking gaze of Tyll Eulenspiegel reflected through a contemporary lens portends of the potential consequences of social disharmony.

My choice of vocabulary may suggest a gruesome read, but that is not so. Whilst I admit to struggling initially (perhaps because of my state of mind rather than through any fault of the author), I did in the end find Tyll to be a very satisfying read; an intelligent book for the inquisitive reader. (I read it in German, and can not speak on the success or otherwise of the English translation.) A historical fiction with elements of magic realism and the picaresque tradition, and a satirical and sometimes comedic tonality that never distorts the horror of the reality that was (in that time). I was struck by how much death there was in life – a nearness to death, to the inevitability of death; something rather not contemplated in our oh so, so enlightened times. And there is this pervading sense of…I don’t quite know how to say it … of what remains when it is all said and done – perhaps it is all the accumulated fictions that ultimately tell the most about an everyday experience of life that we will never know rather than historical facts alone.

One can go through the whole rigmarole about just how much fact may there be in fiction (but not vice versa!), but I don’t approach historical fiction like that anyway. Rather, I read a narrative that may (or may not) spark enough interest such as to pursue historical research for its own sake. Daniel Kehlmann plays imaginatively with his historical figures, and even his fantastical Tyll is out of his time – the original tales placing him in the 14th century and dying in the plague of 1350. Here Kehlmann seems to be more inspired by the 1867 retelling by the Belgian author Charles De Coster, The Legend of Thyl Ulenspiegel and Lamme Goedzak, who placed his Flemish “Thyl” in the midst of the Reformation, and gave him a companion called Nele.

Many of the characterisations are vivid, and I especially loved his “Liz” and had to run to my books to place this Elizabeth Stuart; her inner conversations are full of intelligence and humour, and warm affection for her (rather dim! she says) husband, the unfortunate Winterkönig, and their unforeseen role as King and Queen of Bohemia and the odd chain of events that led to the Bohemian rebellion and the beginning of the Thirty Year War, and a life in exile. And her homesickness for England is touching, specifically her love of its theatre and lyric – named is Chaucer and Donne; unnamed the principal of the magnificent King’s Men, in her father’s service and her most favourite.

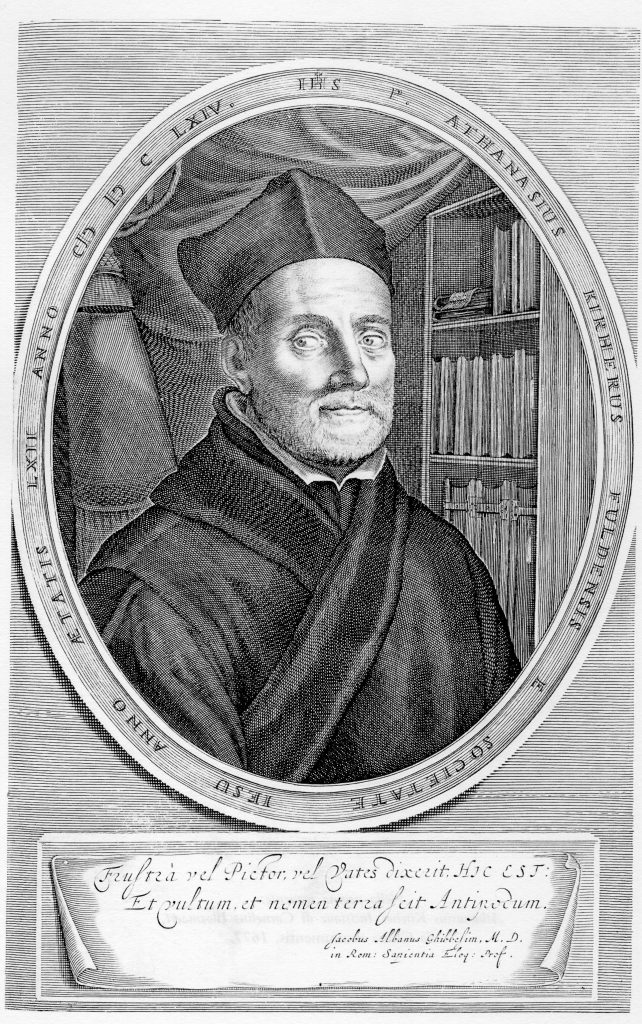

The Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher should be mentioned because it is also within the frame of his life that the story is told – for he was there at the beginning at the judgement and hanging of Tyll’s father and their paths crossed again as the decades of conflict were drawing to a close. The difference being Kircher was indeed very real, as was his theorising of a Katzenklavier, and even his dalliance with dragons is documented.

Kircher’s Wikipedia entry gives hint of a most extraordinary character, not known by me but someone it seems very well researched; one of those sorts whose pursuit of knowledge took precedent over moral certitude and allowed him to adapt to the iterations of terror that defined his time, be they institutional or natural. In conclusion then, I return to where I started, and another odd way in which Daniel Kehlmann’s novel reads into our present, and with a reference from the Wiki entry:

…Kircher took a notably modern approach to the study of diseases… He also proposed hygienic measures to prevent the spread of disease, such as isolation, quarantine, burning clothes worn by the infected and wearing facemasks to prevent the inhalation of germs.

Athanasius Kirchner, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.

Ouch!! Willkommen im Fruhjahr 2020, Pater Dr. Kirchner!

* May 8th 2020: A very positive review here from James Wood in February 17th issue of The New Yorker.