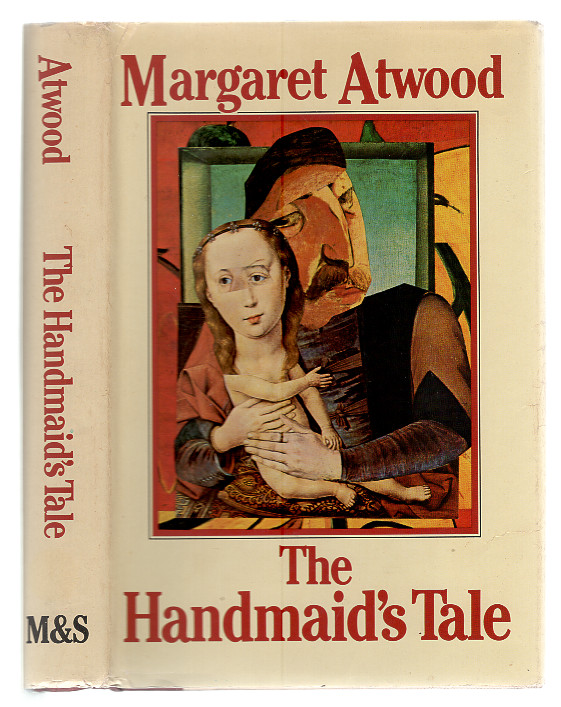

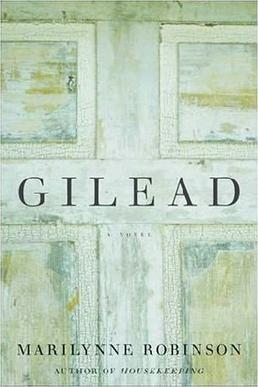

Not too long ago, I read Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, and so it’s hardly any wonder that while reading Marilynne Robinson’s novel I was very much struck by these two very different fictional places being called Gilead – on the one hand Atwood’s dystopian rogue nation and on the other Robinson’s small town anywhere. Certainly, both are American, of a sort; one most definitely imagined, a pessimistic vision. And the other? A place of hope, romanticised like a prairie legend. And both are the scene for patriarchal narratives, albeit of a very different nature, and the biblical reference that lends both their name can be interpreted such as to justify the respective authorial intent. But the diabolical darkness of one is so contrary to the simple human failings and joys of the other, that one is tempted to take note and look not much deeper. But it was the coincidence (?) of place name that interested me, and the parallels that are exposed I find revealing and worthy of some thought.

Firstly, going back to the name. Gilead means “hill of testimony” – at least that is one accepted meaning – and both narratives are presented as testimonies – from a dying Rev. Ames and a handmaid (Offred) on the run (we think!) – and both tell their stories in that temporal fragmented way particular to memory. And as I said above, one just can’t get pass the generations of men and the societies they have defined; be it as men of God offering their interpretations of church and Godliness on a patch of Mid-western earth, or as degenerate Sons of Jacob perverting religion and taking the notion of patriarchy to its radical end in a Godless New England.

It also interests me that, like Atwood’s Handmaids and Commanders, Lila is so much younger than the good Reverend Ames, and this follows the Biblical narratives of old men and young women (especially the Israelite patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, Jacob), and both stories are driven by fertility, not just of man and woman but also of the land and its habitability and production affected by contamination and climate (and one could ask, where lies the fault: with the sins of man or by the will of God). This latter, this equating the people with the land works for both narratives and, as Ames’ would say, that is a wonder.

I am curious as to whether anyone has ever broached with either writer parallels that exist between these two books; a quick google around by me brought nothing much to light. (Though I did find an interesting piece from Alissa Wilkinson at Vox last summer, who seems to have contemplated at least some of the things that concern me. I liked especially her referencing to the hymn “There is a Balm in Gilead”, which I remember being parodied by Moira in The Handmaid’s Tale along the lines of “… a Bomb…”, presumably implying that rather than a healing force it is a destructive force that has gained control.)

The Handmaid’s Tale was written two decades before Gilead. Did Marilynne Robinson read it way back then? Or since? Does she read Margaret Atwood at all? And vice versa? Looking at their biographies, as different as they may at first appear – the American Robinson, as fine in tone and minimalist in terms of publication as the Canadian Atwood is sharp and prolific in output – they share some commonalities; not unlike the Gileads they created. Women of a similar age, recipients of good liberal educations that led to times short and longer in academia, and both committed to literature as their tool to describe the world. They share too in having had an early awareness of ecological issues and the environmental consequences and political dimensions.

And even the most radical differences suggest likenesses. Robinson’s devout Christianity that draws on calvinistic principals is at odds with an Atwood who views the world with an agnostic eye, but both reach back in their respective novels to the American Puritan experience for inspiration – for better or for worse.

Thinking about Puritanism, and how it took on a new form in the first American colonies, I realise how ignorant I am on this subject (hardly surprising!), but these two books have certainly ignited my interest so I intend to pursue a little research of my own.