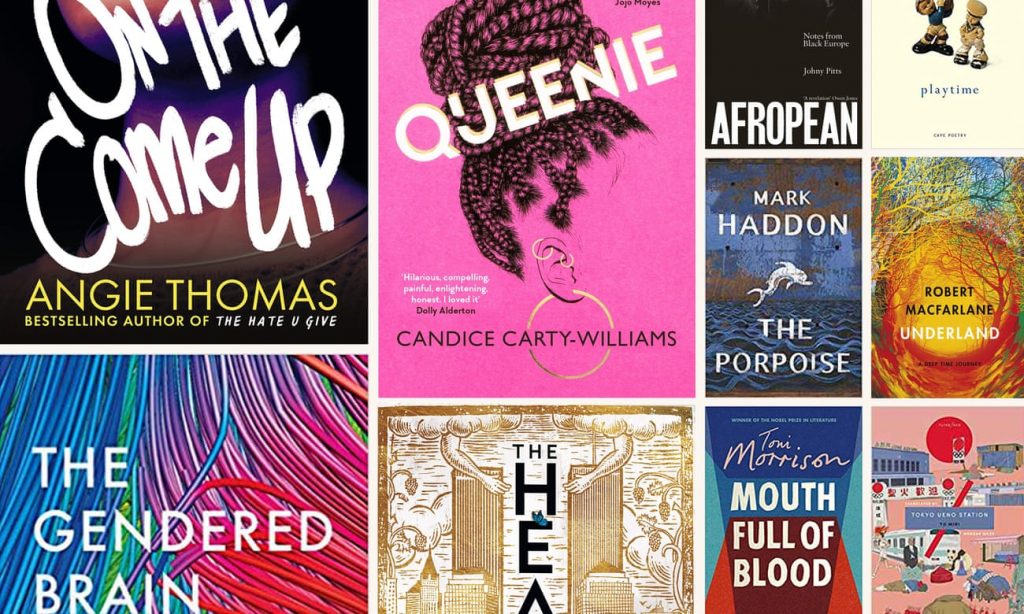

The Guardian: Best books of 2019…to date

More for future reference than anything else – given that I usually have a year (or two, or three …) lag, The Guardian has published a list of their best (& reviewed) for the year to date.

A few of the publications I have been aware of, for example from The Guardian’s must-reads from year’s beginning here , like for instance the new books from Ali Smith, Tana French and Toni Morrison, but there are some that are new to me. That part of me attracted to myth, either in narrative form or as scholarly excursus respectful of the “lay” intelligence, takes particular heed of Natalie Haynes’s A Thousand Ships which gives the women of Homer’s Iliad their very own voice (I know women writers dabbling where they don’t belong is being done a lot of late, but we do have two or three thousand years to catch up on!). And for a different sort of myth, if you will: A History of the Bible: the Book and its Faiths by Oxford professor and Anglican priest John Barton sounds to me like an intellectually stimulating and original work, without an agenda beyond putting fundamental interpretation of all persuasion in its place and the joyful exposition of all the splendours of a literary reading-that’s what I understand from their review anyway.