Nymph & Princess, King & Poet

With book 4 ends the Telemachy, it is now Telemachus’ father, the hero Odysseus, our star (!), who takes centre stage; with his fate resting on the good will and intentions of some powerful women, but above all the continuing favours of daughter goddess Athena and her wily ways of influencing father Zeus to do well by the hero with traits of intelligence and cunning paralleling her own.

Book 5: From the Goddess to the Storm

pp. 180-196

We are introduced to a morose Odysseus on Calypso’s island – held there long captive by the nymph for eternal love’s sake. Years before washed upon her shores, the gratitude he may have felt for the sanctuary she provided has turned to a bitter indifference towards his captor. Her physical attractions and the gifts she bestows no longer temper his misery or distract from his profound longing for his home and wife – Ithaca and Penelope.

Nudged to intervene (by you know who), Zeus sends Hermes to command the release of Odysseus so that he may finally continue on his journey home. Calypso reluctantly complies, and her affections are indeed such that she ensures Odysseus is outfitted such as to bear the dangers of the high seas, though not counting upon the intervention of the forever cranky Poseidon who whips up the fiercest of storms. But, lo and behold, there is another “girl” on his side – the White Goddess, Ino – who drapes him in a magic veil to guide him through the dangerous seas to the shores of Phaeacia, where Athena hovers to keep him safe.

book 6: a princess and her laundry

pp. 197-207

Athena manipulates another beauty, the princess, Nausicaa, to further her rescue plan. Encouraged by a dream to do so, Nausicaa is laundering garments with her slave girls at the washing pools, when the bedraggled Odysseus appears and with words, heavily laden with flattery, seeks her aid. His plea is not denied, for Nausicaa understands the rites of courtesy due to needy strangers, and (now bathed and spruced up some by Athena!) is impressed by Odysseus’ beauty and grandeur. She instructs him on how he may find his way inconspicuously to the town walls; where at book’s end our hero awaits the right time to proceed to the palace of Nausicaa’s father, King Alcinous.

book 7: a Magical Kingdom

pp. 208-219

Enveloping him in her magic mist and leading him under the guise of a little girl, Athena ensures that Odysseus safely finds the King’s palace. As their daughter, so the royal pair Alcinous and Arete offer all due hospitality, their guest having a look and manner such that for a moment he was mistaken to be of godly nature. Odysseus reveals his story of being lost at sea, years spent at Calypso’s pleasure and Zeus’ intervention to set him free; only then to encounter an irate Poseidon and be washed upon their shores, whereupon their daughter saved him. After having eaten and drunk his fill and parried the King’s suggestion that he be a good match for his daughter – but still been assured that they will assist him in getting home, a good bed is prepared for the weary stranger and a feast in his honour is planned for the morn.

book 8: The songs of a poet

pp. 220-239

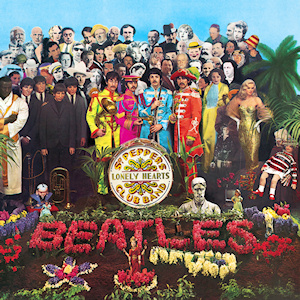

And on the next day there is indeed a worthy celebration in honour of the stranger – a fine banquet of meats and sweets and wines, and games of athletic prowess in which a taunted Odysseus shows too his excellence of person, and a very Homeric poet – the blind Demodocus – sings of the Archaeans and Trojans and of a quarrel between the heroes Achilles and Odysseus (Odysseus weeps!), of the adulterous Aphrodite and Ares, and later, at Odysseus’ request, of the fall of Troy and the Wooden Horse (and Odysseus weeps some more!). Alcinous, alert to all the weeping, demands that the stranger come clean – tell his story.

[22. September 2021] Odysseus weeps and weeps some more as Demodocus sings of the mayhem and blood shed as Troy falls, but it has come to my attention, that the sorrow he exhibits, the tears he sheds, can be interpreted as an asymmetrical act to the grief of Andromache on the death of Hector and her anguish about what fate now awaits her.

Odysseus was melting into tears; his cheeks were wet with weeping, as a woman weeps, as she falls to wrap her arms around her husband, fallen fighting for his home and children. She is watching as he gasps and dies. She shrieks, a clear high wail, collapsing upon his corpse. The men are right behind. They hit her shoulders with their spears and lead her to slavery, hard labor, and a life of pain. Her face is marked with her despair. In that same desperate way, Odysseus was crying [...] Book 8 [lines 521-532], The Odyssey, trans. Emily Wilson (pp. 237-239)

It is really extraordinary how a woman introduced as a simile for the state of the grieving Odysseus then takes on a life of her own in the verse. And that life could be, generically speaking, the widow who has lost her beloved on the battlefield and is facing an uncertain future, or it could be imagined more specifically as Andromache. Though, in the moment, Odysseus’ emotions are being stirred by his intense warrior pride and the desire to hear again tales of days of glory, perhaps I was remiss in not allowing some credence to the possibility that Odysseus’ reaction was not also a gesture of empathy for those who had suffered in Troy; after all he has come some way – and in more than nautical miles – since the Trojan war.