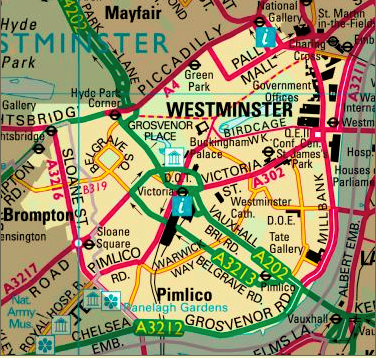

Each aerial view of each mini-cavalcade of darkened Land Rovers led by outriders in royal blue and luminous yellow brings one near to all that topography of land clustered tight, then precisely coded, within the celebrated London environs of SW1; compressed there within its borders all the ruling powers of a kingdom.

A neck of the woods that I know well, albeit from from the vantage point of another SW (storied also but where real people live – or once lived) and from halcyon days long gone, but few I would say have ever journeyed these fabled routes, either actually or on the wings of imagination, as many have done in most recent times gone – as the late summer of 2022 turns to autumn, as a monarch departs the mortal world and another ascends to her place, as a Prime Minister goes and another comes, and as a Prime Minister goes and another comes. I am not repeating myself! Blink and history was there just waiting to be missed.

On Thursday, after 44 (!) days in office, Liz Truss announced her resignation, and today this found its formal conclusion in the requisite audience with King Charles III at Buckingham Palace and, shortly thereafter, Rishi Sunak, the newly elected [sic] leader of the Conservative Party, being invited by the King to be his Prime Minister.

From memory: After the wheels finally fell off Boris Johnson’s government at the beginning July, a convoluted process for the leadership of the Tories began with the whittling down to two contenders – Truss and … yes, Sunak! – and continued through the summer with a series of so-called “hustings”. Sunak was favored by conservative parliamentarians and Truss by Party members and, yes, the latter trumped the former. Two days after receiving Johnson and Truss (not in SW1, but Balmoral – for reasons which were sadly to become clear) and doing that which the monarch is anointed to do, the Queen died. Granted, an interrupted start extraordinaire but then Truss seemed to tout the powers of disruption. All very well, one could say, but did she not know that in times of global crisis markets and their makers crave at least the promise of stability. In a matter of weeks a complete economic framework, misguidedly constructed on a toxic mix of low taxes and high borrowing lay in shambles, and with it Liz Trusses job and reputation.

And so it was, this time round, in just a few days, and with Boris Johnson returning with fanfare from a Caribbean jaunt, the Tories heaped on the wearied Brits another leadership “election”! More skillfully modified this time round, with a set of rules that would, with any luck and some reason, circumvent interference from pesky Members. And in the end, so it did: Bojo knew when to fold, as did, albeit at the last moment, another penny pretender (called Mordaunt), and Rishi Rich was left holding the winning hand. Like democracy is a game of poker!

Wikipedia has an entry with the title October 2022 United Kingdom government crisis where you and I both can check the chronology of events, whereby they helpfully suggest in the header that this “Not […] be confused with July 2022 United Kingdom government crisis.” !

On Rishi Sunak, putting aside the politics, it should be said that he is the first Prime Minister from an ethnic background (okay, there is the Disraeli exception – not quite the same thing I would suggest) – his parents, of Punjabi descent, migrated to the UK from eastern Africa in the 1960s; married to the daughter of an Indian tech. billionaire (with modest beginnings); a practicing Hindu. In other words, a biography, irrespective of the advantages granted to him by good fortune, and fortune, that only a very few years ago would have made a rise to the highest echelons of power almost inconceivable. Meritocracy sometimes works it seems. A remarkable story in many respects, and that Sunak’s success should correspond with Diwali, the Hindu Festival of Light, and in this year that remembers the end of the Raj and the 75th anniversary of Indian independence, is highly symbolic and one of those strange quirks of fate.