An epic wait nears its end. A tweet from Emily Wilson in April (overlooked by me because an aversion that began with Trump a few years ago morphed into an aversion to Musk – from which it follows that I visit ‘X formerly known as Twitter’ but infrequently) alerts to the September 26 publication of her Iliad translation. I sort of knew this, but the official word is always reassuring. And, yes, the cover design is ‘glorious’ I think – I note the red hues in contrast to the blues of the Odyssey cover; the colors of bloody battle and wide seas respectively.

Category: Classical Diversions

A collection of posts relating to the ancient and classical world.

One poet many voices

In English alone there are about 100 translations of Homer’s Iliad; to which we may add Emily Wilson’s new translation (to be published in September presumably). Her excellent comparative essay in The New York Times shows the range of interpretive possibilities of Homer’s epic poem through the ages – from the original to George Chapman in 1611 through to the contemporary culminating with that of her own (a sneak preview if you will!), in various metrical forms and not, rhyming and not – and exemplified in the memorable scene when Hector bids farewell to Andromache and his baby son (book 6. 482-497).

Wilson shares her translation of this passage. Again, as she did with Ulysses, she uses the iambic pentameter of Shakespeare and Milton, and her vocabulary choices and turn of phrase in this small sample already recall to me very much that work. And reminds me how very much I have been looking forward to her Iliad.

Murder in Trieste

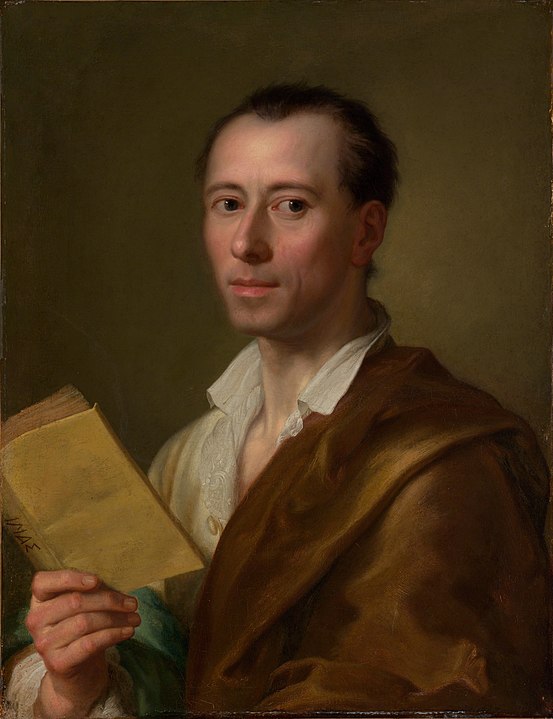

I intermittently catch the BBC Radio 3 cultural program “The Essay”, and are often surprised by its content, but it actually took an article in the Frankfurter Allgemeine to alert me to these episodes (still available as I write on Sounds) about the circumstances surrounding the 1768 murder in Trieste of Johann Joachim Winckelmann – considered to be one of the first practitioners of what we would now call art history and archaeology. I say that, but it is more. The cultural historian, Seán Williams, is also telling the wider narrative of a celebrity “gay life” (and death) during the Enlightenment – what could be done and what not, where and with whom – and how it has been interpreted in the afterlife, both in respect to Winckelmann but in the myth building around cultural icons.

Winckelmann interests me. He turns up in this blog post, in which I touch upon newer research and reconstruction methods in polychromy that supports the view that the artifacts of antiquity were very colorful indeed; running counter to the monochromatic orthodoxy which had first arisen during the Renaissance but the certainty about which began to crack during the Neoclassical period of the 18th century – a cultural movement and time of which Winckelmann was a “mover and shaker”. Under nearer scrutiny, traces of pigment were being observed for the first time on objects, and even Winckelmann (albeit belatedly) changed his stance. But, by the 20th century, and for whatever reason – racism, the aesthetic of fascism it has been suggested – all the scholarship and practical methodology of the 18th century was being rejected in favor of the marble white, purity narrative, and prevails still in the contemporary consciousness. The latter is hardly surprising when the artifacts and fragments on display in the museums of the world mostly have very little pigment remaining, and labels are not always explanatory.

As I say, Johann Joachim Winckelmann interested me anyway, but Sean Williams’ radio essay has added an extra dimension. (Here, in his own words, a short accompanying text.)

Tomb Raider

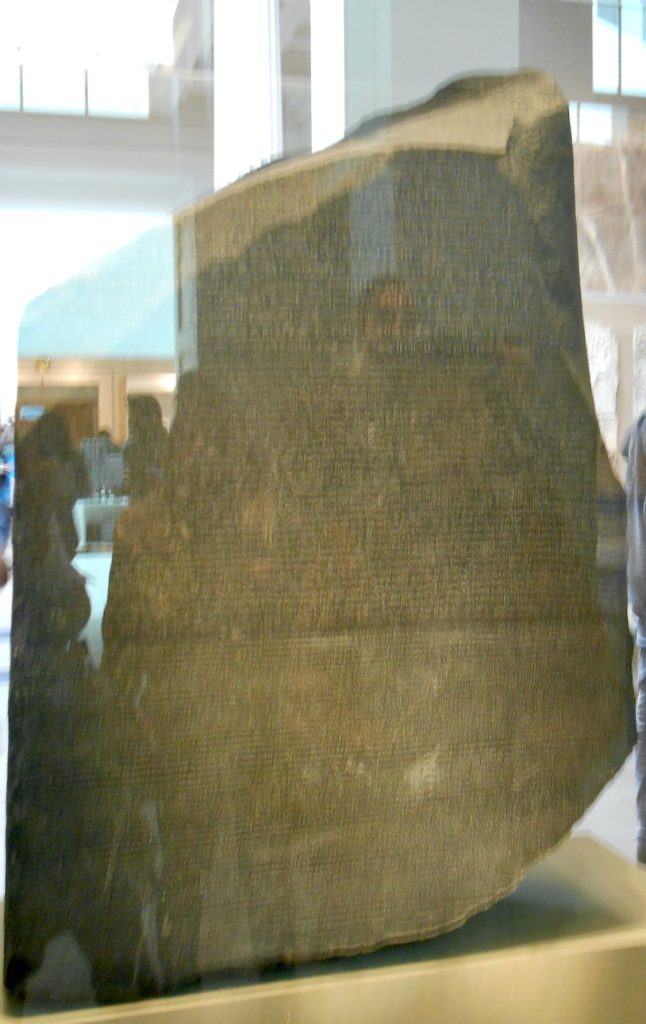

Still a topic of contention and with new evidence surfacing a hundred years on; the excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun in November 1922 by a team under the patronage of George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon and led by the Egyptologist Howard Carter. As I mentioned here in discussing the Rosetta Stone and other artifacts strewn far and wide, this, perhaps the most famous of all plunderings, also remains a matter of heated debate between the governments of Egypt and the United Kingdom.

The archaeological record of the excavation was bequeathed on Carter’s death to The Griffith Institute at Oxford University which provides for a comprehensive online resource – original documentation, photos, drawings. What of course it does not do is delve into the nitty gritty of questions of ownership and restitution.

Marbles & Stones

The British Government line for why they have maintained a relatively passive role in deciding the fate of the stolen Parthenon Marbles (I’ve always said “Elgin Marbles” – me thinks that ain’t exactly p.c. these days!) has always rested strongly on the reasoning that the spectacular artifacts were removed from the Acropolis and brought into the UK by Lord Elgin in the 19th century – that is, it was a historically private initiative, unhindered by the Greek officialdom and following international and diplomatic protocols in place at the time, and over which the Government had little to no influence then and presumably no legal liability now. In the light of this, a report in The Guardian a couple of days ago about research suggesting that the foreign secretary of the day, Viscount Castlereagh, was, in fact, very much involved in the initiative and in facilitating the import of the marbles, offers an interesting new angle in what must be one of the longest and most famous disputes concerning stolen antiquities.

The publication of these findings comes at a particularly timely moment it has to be said; coming on the back of a renewed campaign by the Greek government, partly inspired by the sudden change of stance by The Times at the beginning of the year and public opinion in the UK in general, and the British Museum showing signs of a willingness to explore compromise solutions (talk for instance of a so-called “Parthenon Partnership” and a new Parthenon Project.).

Staying at the British Museum: There is the matter of the Rosetta Stone – famously, the engraved artifact with which Jean-François Champollion went about his decoding of the hitherto puzzle of hieroglyphs. The physical object of course is one thing, but just as important, perhaps, is the way in which the astounding work of Champollion and others shone new light upon the richness of ancient Egyptian civilisation – their society, customs and belief systems. In recognition of Champollion’s scholarship there is a major exhibition Hieroglyphs: unlocking ancient Egypt at the British Museum through to 19 February 2023 (and I note an extended blog piece by the curator, Ilona Regulski). And another at the Louvre satellite in Lens, Champollion: La voie des hiéroglyphes (the webpage is only in French, but the objects can be looked at) until 16 January.

Not quite as loudly as Greece, but Egypt too has called for the return of their “lost” heritage over the years. The loudest, though no longer in a governmental role, has been the renowned (and publicity savvy) Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass who regularly pleads for the Stone’s restitution (as he likewise does for Nefertiti’s return from Berlin). In some ways this case is more complicated, in that the Rosetta Stone was amongst the many artifacts that were handed over to the British in a formal agreement as a result of the capitulation of Napoleon’s army in Egypt. Though one could conclude: Okay, so the French excavated, confiscated – maybe nicked – all this stuff and the Brits just help themselves to the spoils? What!

I admit to being a convert tending more to the ‘return’ side of the argument. Way back whenever I was amongst those (many, I believe) interested observers of the mounting controversies who just sort of presumed western museums (located in democratic countries, in more moderate climatic regions – both factors remain good – but not defining – arguments) had the space, financial and technical resources, expertise to best ensure the preservation of some of the treasures of world civilization. Unfortunately, it has to be said, many of these institutions (mostly led by an older generation and with the tacit support of their governments) have over decades been too reluctant to seriously engage with the claims made by the nations and peoples from whence many cultural objects have originated and, even when, have confronted the claimants with a sometimes patronizing, often impatient and nearly always paternalistic attitude. Ultimately, I think, one has to be prepared to accept the good will and intentions of those who seek restitution of their property and their right to make decisions that they deem in the best interest of the preservation and continuity of their cultural heritage. There are enough examples of how that may happen – with partnerships, exchanges, even new museums.

It seems, then, after years of bulwark tactics, the British Museum may be finally progressing towards an inclusive and respectful course of cultural and intellectual exchange. And it is not alone, for younger generations are taking on leadership roles at many other of the world’s great institutions; generations that are more diverse and with broader cultural visions. This, I think, is good news (something at a premium these days!) for the many nations that are reorganizing their cultural legacy in a post-colonial world.

Coloring antiquity

This NYT article alerted me to the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition entitled Chroma: Ancient Sculpture in Color; an adaptation it seems of that which I viewed at the Liebieghaus (the home, so to speak, of many of the exhibits) in Frankfurt – there called “Gods in Color” – in February 2020, and about which I posted here. In fact, various versions have been touring the world over the last decade or so, but given the larger space available (not to mention, the budget) it is possible that the Met show is more ambitious. The Met web page is very informative (as was also that during the Frankfurt show) but new is an app than encourages virtual recreations and reflects the collaborative work of those behind the polychromy project. (And everybody knows nothing works without an app these days!)

Of course, times being as they are, it is inevitable that the conversation surrounding the content and merits of the show would be dominated by matters of identity. And given the particularities of the project and the issues that arise from the reconstructions of Vinzenz Brinkmann and Ulrike Koch Brinkmann, the pivot is not hard to make.

And the NYT piece certainly doesn’t let down in this respect; pointing out how the Brinkmann team’s reconstructions have led to degrees of disquiet in academic and research circles. It seems some would contend that these particular reconstructions have been afforded such celebrity in recent years that it is often overlooked that they, in fact, represent only the scholarship of one pair of researchers, and should not be seen as a definitive verdict. This further leads to wide-ranging debates (often motivated through self or particular interest) on variations of polychromy and, of course, whiteness – and not just during antiquity. In this respect, the Times points to an interesting 2017 blog post from the historian, Sarah E. Bond, and this very lengthy and very excellent 2018 New Yorker article.

The following YouTube video (also on the Met site) is an excellent introduction to the scholarly and technical background to the project.

By the way, I was incredibly informed by the exhibition in Frankfurt – loved it, really; even if a favorite jacket came to grief in the cloakroom and it was to be my final cultural adventure before the pandemic took over our lives. If I knew anyone in New York I would highly recommend heading for Fifth Ave. (through March 26, 2023), and I am also fairly sure it will turn up elsewhere in the future – probably with new exhibits.

Wilson’s “Iliad” translation – next year.

August 13 2023: Here embedded was a tweet (from 2022) announcing Emily Wilson’s translation of Homer’s The Iliad for 2023; now defunct. No matter; the translation is on its way – on our bookshelves in the next weeks as I write. Nor, by the way, can I any longer get to the May 30 thread which inspired me to the musings below. Rather than deleting my post, I offer Wilson’s thread from about the same time on the nuances required – and the compromises that sometimes have to be made – in Homeric translation.

“A classic translator’s dilemma, … One language makes a distinction where another makes none.”

Should one dare to flitter into the Twitter-sphere (which I do these days but sparingly!), Wilson’s May 30 2022 thread cleverly teases out how very much Homer’s epic tale evidences the absurd constancy of the human condition – for better or worse, in good times and bad – through the span of our existence. Fear not – Dr. Wilson is not on the brink! Of myself I am not so sure…

Don’t tell me about dead heroes, dead languages, dead civilizations, enlightenments and awakenings, beginnings and ends of history … ! On whim and with change of garb and scenery we play what we deem our original role; every night an opening night, an acting out of our own perceived exceptionalism.

The truth written in memory is another: Like the river from its source, we flow onward, snugly fitted in the bed made for us; accumulating and losing sediment along the way, wasting nothing more than we want, but remaining essentially the same. We are our ancestors’ heirs; a mere appropriation over time of ourselves, intent on satisfying ourselves for life’s moments; at once brief and eternal.

Post-script: The Odyssey Book 8

Copied beneath is a post-script to my reading of Book 8 of The Odyssey, which I have updated here.

[22. September 2021] Odysseus weeps and weeps some more as Demodocus sings of the mayhem and blood shed as Troy falls, but it has come to my attention, that the sorrow he exhibits, the tears he sheds, can be interpreted as an asymmetrical act to the grief of Andromache on the death of Hector and her anguish about what fate now awaits her.

Odysseus was melting into tears;

his cheeks were wet with weeping, as a woman

weeps, as she falls to wrap her arms around

her husband, fallen fighting for his home

and children. She is watching as he gasps

and dies. She shrieks, a clear high wail, collapsing

upon his corpse. The men are right behind.

They hit her shoulders with their spears and lead her

to slavery, hard labor, and a life

of pain. Her face is marked with her despair.

In that same desperate way, Odysseus

was crying [...]

Book 8 [lines 521-532], The Odyssey, trans. Emily Wilson (pp. 237-239)

It is really quite extraordinary that it is a woman who is introduced as a simile for the state of the grieving Odysseus, and then takes on a life of her own in the verse. And that life could be, generically speaking, the widow who has lost her beloved on the battlefield and is facing an uncertain future, or it could be imagined more specifically as Andromache. Though, in the moment, Odysseus’ emotions are being stirred by his intense warrior pride and the desire to hear again tales of days of glory, perhaps I was remiss in not allowing some credence to the possibility that Odysseus’ reaction was not also a gesture of empathy for those who had suffered in Troy; after all he has come some way – and in more than nautical miles – since the Trojan war.