One should need not say, but I will: With A Room Of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf laid the foundation to a way of thinking, not just about women’s writing, but what it is to be a woman in a man’s world and what it means to be represented in a man’s version of history, that has influenced generations through to the present. Here, in conversation with three who may very well count themselves as beneficiaries of Woolf’s legacy, is Melvyn Bragg’s contribution to the continuing exploration of how a couple of lectures to a roomful of young women in Cambridge almost a century ago evolved into a defining document for the ambitious modern woman – Woolf’s unique contribution to the greater quest for emancipation and equality. (Embedded below from Spotify.)

Tag: Virginia Woolf

With baton in hand: On Tár & Ethel Smyth

Tár has been on my mind. A Todd Field film released at the end of last year; much talked about, though receipts suggest not seen nearly as much – albeit more so of late (award season!) and much more so since its wider release outside of the US. And looked upon mostly favorably and sometimes not. For now I can only add that it says much about these fractious times that a film about an absolutely not-nice but lauded female conductor – that all agree is brilliantly portrayed be Cate Blanchett – could be hauled from the creative space of the movie theater and plunged into the vitriolic and intransigent arena of the culture-war theater. I will see it and then have my say. (Though be warned my impartiality is not assured: most anything with Blanchett – with the exception of Armani ads! – is okay by me. I like to think we sound alike.) And have been encouraged to do so by a just read piece by Nicholas Spice in the LRB (Vol. 45 No. 6 · 16 March 2023) that broadly considers the art of conducting through Field’s film, a recent translation and commentary of Richard Wagner’s essays “On Conducting” (amazingly open access at JSTOR) and an experiential memoir by Alice Farnham.

There is probably no reason Spice should mention Ethel Smyth in his essay, but I would not have minded her spirited and stubborn presence; for she, too, has been fluttering around in my head. In the midst of my continuing Virginia Woolf stuff, I have been occupied with that period at the beginning of the 1930s during which Woolf found herself the object of the affections of the celebrated composer, conductor and suffragette; the attentions of whom aroused and irritated at the same time.

At the beginning of 1931 Woolf attended rehearsals of Smyth’s opera The Prison, adapted from a poem by her friend Henry B. Brewster, and then its London premiere performance on February 24. All did not go well. Accordingly, a very belated first recording in 2020 and its warm reception is of interest, and to be complemented by this essay, also from The Guardian, by Leah Broad.

Mysterious is this friend of hers, Henry Bennet Brewster, about whom information (in the internet anyway) seems scarce* but, when unearthed, is often in respect to his relationship with Smyth; his own work, seemingly, to have fallen into obscurity. Of any substance I can only find this 1962 essay by Martin Halpern in American Quarterly (pub. The John Hopkins University Press) held at JSTOR. (*Halpern’s essay suggests more could be learned by way of others, like another even more famous friend – Henry James. A task for another time. But the rediscovery of Brewster that Halpern hoped for sixty odd years ago seems not to have eventuated – unlike that of Smyth. Unless of course she has coattails to match her tailcoats!)

The Prison can be sampled below on Spotify; other interpretations of her work can also be heard there (with an account) including Mass in D from the BBC Symphony Orchestra; also resurrected and recorded for the first time in 2019.

In a diary entry made following the 1931 rehearsal of The Prison, Woolf writes a colorful -and comical – portrait of Ethel Smyth, which concludes with her being struck that Smyth, so practical and so strident in common discourse, could spin such music – so coherent, so harmonious – and asks the question: “What if she should be a great composer?” Well, that I cannot answer. But, what can be said, is that Dame Ethel Smyth has been granted that rare gift of an afterlife; enough qualified others over the years having concluded her music had merit and warranted reappraisal – and, this, long after her once radical presence in this mortal world had seemingly been confined to feminist folklore, footnotes – or even the diary and letters of Virginia Woolf.

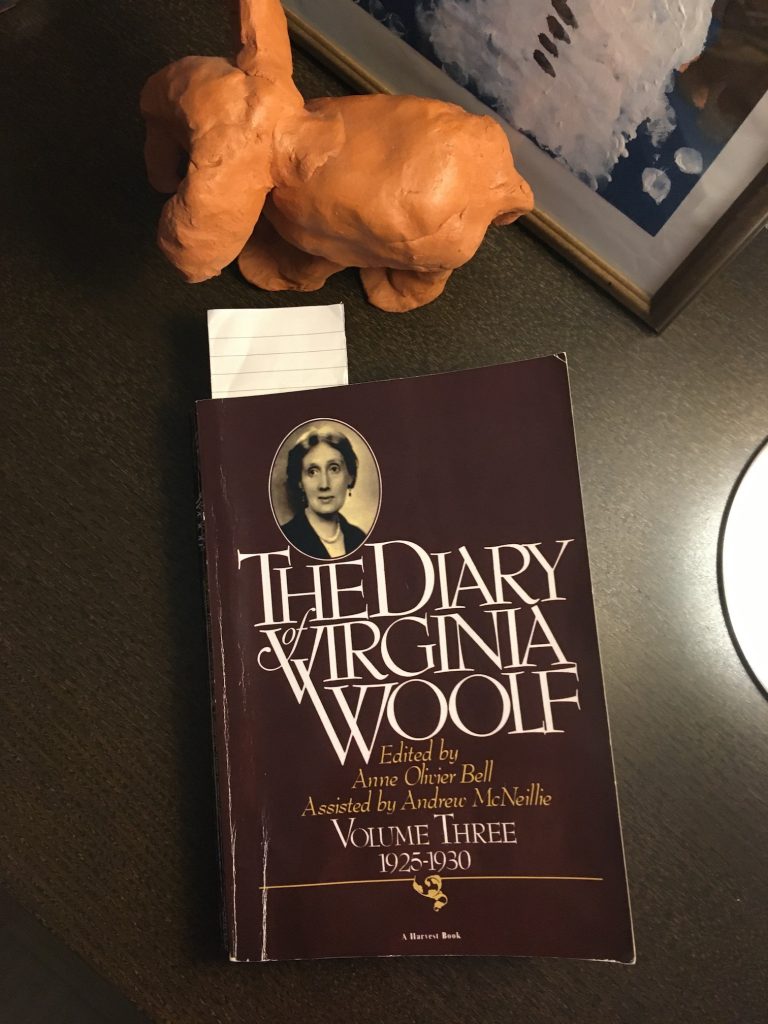

The Diary of Virginia Woolf (3)

VOLUME Three: 1925-1930

Extraordinarily it has taken me two years to write up this Volume Three of Virginia Woolf’s diary. Absurd, really. But here it is!

It is left to be said, as I have vowed before I do so again; with Volume Four encompassing the years 1931- 1935 (and to be started upon post haste!) I shall endeavor to be stringent and selective. But, believe me, with Woolf that is easier said than done. And, whilst ambition is a worthy trait, and a very Woolf-ish one at that, I dare not predict a time frame for the completion of this volume either!

The Bennett of Bennett & Brown

Following from my previous post, if you get another shot at The Spectator, A.N. Wilson also had something to say earlier in the year on Arnold Bennett and a new biography by Patrick Donovan called Arnold Bennett: Lost Icon (Unicorn) which couldn’t help but interest me.

Now for me, Bennett is only the Bennett of Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown; that essay from a certain Mrs. Woolf that is the wryly imagined culmination of the legendary dispute between herself and the aforesaid, and is a proxy – so to speak – for that greater reckoning between proponents of realism and modernism in the early 2oth century novel.

More than a little snarky when it comes to Mrs. Woolf, in my opinion, is the Mr. Wilson. Nor quite accurate either. Bennett and Woolf were contemporaries only up to a point, more precisely their careers briefly overlapped; most of Bennett’s works (including the “Clayhanger” series) were published in the first two decades of the century, and Mr. Bennett’s criticism of Mrs. Woolf’s third novel Jacob’s Room came in 1922 and before her real rise to literary fame with Mrs. Dalloway. And Wilson’s claim that she (and others) had it in for Bennett because he was too “middle-brow” is rather specious. On the contrary, one could contend; it was Mrs. Woolf’s “Mrs Brown” who displayed various degrees of the too easily maligned “middle-brow” – Mrs. Woolf is rooting for the “middle-brow” with all their peculiarities and inconsistencies and against easy assumptions made of them. Her point is: if it were to be a “Mr. Bennett” who was to imagine and describe his “Mrs Brown”, he would have her been imbued in his own image, reflecting the world as he saw it.

I do understand Mr. Wilson’s loyalties towards Mr. Bennett – the links between the two men: Stoke-on-Trent, potteries, Wedgwood are clear. And Clayhanger and The Potter’s Hand stand only a century apart in the setting and a (different) century in the writing of; neither of which I have read, but am inclined to.

Aftermath

Diverging to dabble in some amateur wordsmithing (is that a word?); inspired by a word pondered by Woolf; inconsequential to all intents and purposes and simply said in passing, but worthy of thought.

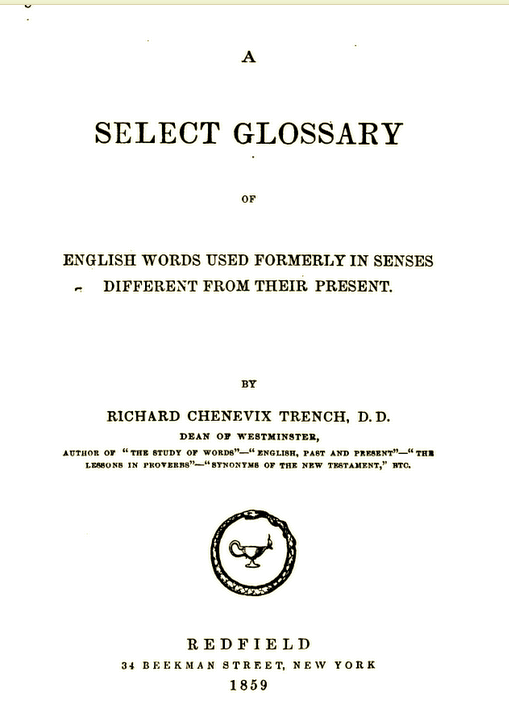

In her diary entry of Wednesday 7 November 1928, Virginia Woolf wonders at her poor physical and mental state in the aftermath of the publication of Orlando. And true to form, that contemplation once written sets her searching mind, unhindered by its fragile state, momentarily meandering, and she wonders about the etymology of a rather ordinary word, the word “aftermath”, and turns to, as she says, “Trench”, for some reconciliation.

Well, none was forthcoming from the said Trench. But I was curious and wondered at her reference, and a footnote explained the tome to be: A Select Glossary of English Words used formerly in senses different from their present (1859) compiled by Richard Chenevix Trench. Rather dated, even during Woolf’s time to be sure, and one may presume that it was long in her possession; from her father’s library perhaps.

To my surprise a digitized version (of the American edition) is on the hathitrust website, and this curious work of reference is certainly well worth a browse – even if it doesn’t help on the matter concerning “aftermath”!

Some further research on my part indicates that the word does in fact fit the criteria insinuated in the title, so the good Mr. Trench was indeed remiss.

aftermath (n.)

1520s, originally a second crop of grass grown on the same land after the first had been harvested, from after + -math, from Old English mæð “a mowing, cutting of grass,” from PIE root *me- (4) “to cut down grass or grain.”

Also known as aftercrop (1560s), aftergrass (1680s), lattermath, fog (n.2). Figurative sense is by 1650s. Compare French regain “aftermath,” from re- + Old French gain, gaain “grass which grows in mown meadows,” from Frankish or some other Germanic source similar to Old High German weida “grass, pasture.”

Online Etymology Dictionary

A modern definition, “figurative sense” as mentioned above or in the original might read:

aftermath | ˈɑːftəmaθ, ˈɑːftəmɑːθ | noun

1 the consequences or after-effects of a significant unpleasant event: food prices soared in the aftermath of the drought.

2 Farming new grass growing after mowing or harvest. ORIGIN late 15th century (in aftermath (sense 2)): from after (as an adjective) + dialect math ‘mowing’, of Germanic origin; related to German Mahd.

(My) Apple Dictionary

I note that the Online Etymology entry suggests the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem so named to further illustrate the meaning of the word, and it does so in a lyrical fashion. The poem (see below) appears to have been first published in 1873, and I make the observation that, in the sense that it combines the agricultural meaning with the figurative idea of change – natural and man-made – and what remains, that Longfellow may have been moved – even subconsciously – by the slaughter upon the battle fields of the Civil War – and its aftermath. (I don’t know this, of course, and probably am influenced by Siegfried Sassoon’s 1919 poem also called “Aftermath”; in which the aftermath in question is that of the First World War – no tepid “gloom” to be found in Sassoon’s poem, rather the stark, bitter reality of war.)

Aftermath by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow When the summer fields are mown, When the birds are fledged and flown, And the dry leaves strew the path; With the falling of the snow, With the cawing of the crow, Once again the fields we mow And gather in the aftermath. Not the sweet, new grass with flowers Is this harvesting of ours; Not the upland clover bloom; But the rowen mixed with weeds, Tangled tufts from marsh and meads, Where the poppy drops its seeds In the silence and the gloom. - Poetry Foundation

There is no need to connect Longfellow with Trench, but I can’t resist. Both were born in the same year and died only a few years apart. Trench (1807-86), for a time Dean of Westminster, is buried in the knave of the Abbey and Longfellow (1807-82) is one of the few Americans, and the first, to have a memorial dedicated in Poet’s Corner at that same venerated place. Whether the pair met during any of Longfellow’s sojourns to Europe I couldn’t say but, even had they, “aftermath” probably didn’t arise in polite conversation, for had it done so Trench would surely have recognized the special characteristic of interest to him and noted it for his scholarly volume; and many, many years later Virginia Woolf’s curiosity could well have been quickly satisfied. Was she ever the wiser? Did she inquire of Leonard or one of her many gentleman (or not so) farmer acquaintances in the home counties?

Though I can find no direct reference, Virginia Woolf’s father would surely have made the acquaintance of Trench – the man. With Longfellow, though, I can make a connection – albeit fleetingly. In Frederic William Maitland’s The Life and Letters of Leslie Stephen (for which Woolf was a source), a note made by the subject for October 7 1863 during an extended Summer in the United States records an encounter (presumably through James Russell Lowell – who would remain a life time friend) in which Stephen describes Longfellow as “a pleasant, white-bearded, benevolent-looking man of very quiet manners, who talked agreeably but not poetically (?) with a want of (the?) readiness (?) which appears to be characteristic of literary gents in these parts …” [p.118]. (Read on a little and one learns Stephen also met Seward and Lincoln – sort of – in Washington! The first did not particularly impress, and the second more than he expected.)

What a rabbit hole did I just fall down!

Modern Reading

Whether over lunch, or in the midst of bedtime ritual, beginning tomorrow and for ten consecutive weekdays (Jan 24 – Feb 4), BBC Radio 4 presents a reading of Mrs. Dalloway; embedded within what the BBC calls a “celebration of the birth of Modernism a hundred years ago”. Here, the reference is to literary Modernism and the publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses in 1922 (and Eliot’s The Waste Land). Virginia Woolf’s ‘one day’ novel was published three years later, but fits very well in the modernist tradition – and may justifiably be considered (by the broadcaster) more readable (and listenable) than Joyce’s epic work; dense as it is in allusion and parody.

Start the Week tomorrow morning (with Kirsty Wark – the third presenter in three weeks – and I am still getting used to NOT starting the week with Andrew Marr!) starts the season with a discussion that broadens the scope of modernism beyond the literary – into the visual arts, music and the public space. One of the guests is Matthew Sweet whose ten part series 1922: The Birth of Now also begins tomorrow (through to Feb 4). [BBC is quite generous, and most of these links should remain live for some time.]

Presumably, there is more in store across the BBC but I can’t find the theme centrally organized (generally this is a problem with Sounds – and I know I’m not alone in this opinion!). I actually only became aware of an upcoming “Modernism” project through a passing reference on Feedback at the end of last year and was reminded with a programming note on Open Book last week. That episode, by the way, is all about Ulysses, and listening to the very interesting participants has motivated me to consider (and not for the first time, and as an important condition) diving in. Given this interest of mine in the modernists, and my interest in their interest in the ancients, I shouldn’t need to be pushed (one would think), and rather have been tempted to jump in long ago. Or do I have an insurmountable interest conflict?

Anyway, I have at least tracked down a very good digital version of Ulysses, and there is no shortage of study material, so I will collate what I have in a separate post for future reference. For the moment, may I just refer to Virginia Woolf’s struggle with Joyce (which she never really resolved – personally, I’m not totally convinced she read Ulysses in its entirety nor any of his other works) in particular and, more generally, Volume 2 of her diary which includes this year; one which for her was just another, and was to become for us (and maybe posterity), and unbeknownst to her, much more.

Housekeeping at the Dalloways

With the end of year two of the pandemic, I note with pleasure – whereby, in these complicated days, that a relative state of being – where it was that one of our literary flights of fancy led. And, that was back to the London of a century ago, and all that could happen on just one day traversing the topography between Westminster and Bond Street – on the ground, in the heart and in the head.

A particular literary journey inspired, at least to some extent it seems, by the publication of two new editions of Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway – one from Penguin Random House (with a forward by Jenny Offill and introduction and notes by Elaine Showalter) and an annotated edition from Merve Emre published by Liveright (w.w. norton). Or was it the other way round, and these publications came with an awareness of renewed interest and the potential of a new readership amongst younger generations?

Whichever, as a matter of ‘housekeeping’, and before they go astray amongst my chaotic collection of bookmarks and the like, following are links to just three of the articles that I have collected during the year. (Some other good pieces, unfortunately, require subscriptions.)

- “The Great Novel of the Internet Was Published in 1925” by Megan Garber at The Atlantic. (Limited access.)

- “The Work of Living Goes On: Rereading Mrs Dalloway During an Endless Pandemic” by Colin Dickey at Literary Hub.

- “Mrs. Dalloway: Secularism and Its Enchantments” by Jared Marcel Pollen for Quillette

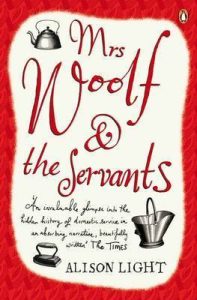

Angels grounded

Alison Light’s 2007 book Mrs. Woolf and the Servants – referred to by me here – is indeed a wonderful read, and for many reasons. Significantly, it goes some way in satisfying my curiosity about the complicated relationship of the said Mrs. Woolf with her servants, and, more generally, in offering through this particular example an engrossing and informative account of the domestic power structures of the middle and upper class households (in Britain), and as a microcosm of the hierarchical distribution of power in greater society, from the end of the Victorian era through to the post-war twentieth century. The gap in my own knowledge was quickly apparent – and gaping! – and Light’s book has gone some considerable way towards remedying my ignorance.

Even from the prologue, I was heartened to read that Alison Light’s motivation for writing the book came from her reading of Virginia Woolf’s diaries and her discomfort, on one hand, and fascination on the other, with Woolf’s language concerning her domestic help over the years, and like me especially with respect to Nellie Boxall. (And I must add: it was just as heartening to hear a British scholar of such standing – and to the Left! – admit to her previous ignorance of the historical importance of domestic service in Britain, and especially for women.)

Broadly chronological, the book traces the history of domestic servitude parallel to that of Virginia Woolf’s life. But ‘parallel’ is a misplaced word here (when thinking about time it may always be!); more precisely, these lives and histories are intertwined in ways obvious and not so; imbued with a public presence that abides by social norms, and a behind closed doors intimacy that is mutually dependent (and, as Light says, unequal); in both spheres easily sentimentalized – then and now.

Woolf is not necessarily the star of this narrative, but rather the accompaniment for the lives of others: of Sophie Farrell, the treasure of the Stephan household in late-Victorian Hyde Park Gate, of Nellie and Lottie Hope, inseparable, in service and out, almost a life long, and of the Batholomews and Annie Thompsett and the Haskins and Louie Everest all who made Monks House the “home” Woolf had needed for her emotional well-being and creative and professional development as a writer. Would she have been generous in accepting this supporting role? I think so, I hope so.

And, as employers, the Woolfs are hardly set decorations – it is important what Light has to say about their role as representative of an intellectual class in the first half of the twentieth century: the disparity that existed between the political and societal agenda that was being propagated and the actuality of a way of life that contributed to the cementing of rigid class structures. I think it is fair to say that it was the highly political Leonard who spoke and wrote loudest on the rights of the working class, but maintained an imperious attitude to those employed in his own home.

Continue reading …