Diverging to dabble in some amateur wordsmithing (is that a word?); inspired by a word pondered by Woolf; inconsequential to all intents and purposes and simply said in passing, but worthy of thought.

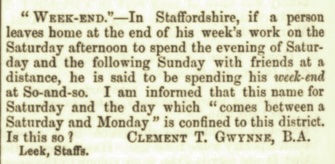

In her diary entry of Wednesday 7 November 1928, Virginia Woolf wonders at her poor physical and mental state in the aftermath of the publication of Orlando. And true to form, that contemplation once written sets her searching mind, unhindered by its fragile state, momentarily meandering, and she wonders about the etymology of a rather ordinary word, the word “aftermath”, and turns to, as she says, “Trench”, for some reconciliation.

Well, none was forthcoming from the said Trench. But I was curious and wondered at her reference, and a footnote explained the tome to be: A Select Glossary of English Words used formerly in senses different from their present (1859) compiled by Richard Chenevix Trench. Rather dated, even during Woolf’s time to be sure, and one may presume that it was long in her possession; from her father’s library perhaps.

To my surprise a digitized version (of the American edition) is on the hathitrust website, and this curious work of reference is certainly well worth a browse – even if it doesn’t help on the matter concerning “aftermath”!

Some further research on my part indicates that the word does in fact fit the criteria insinuated in the title, so the good Mr. Trench was indeed remiss.

aftermath (n.)

1520s, originally a second crop of grass grown on the same land after the first had been harvested, from after + -math, from Old English mæð “a mowing, cutting of grass,” from PIE root *me- (4) “to cut down grass or grain.”

Also known as aftercrop (1560s), aftergrass (1680s), lattermath, fog (n.2). Figurative sense is by 1650s. Compare French regain “aftermath,” from re- + Old French gain, gaain “grass which grows in mown meadows,” from Frankish or some other Germanic source similar to Old High German weida “grass, pasture.”

Online Etymology Dictionary

A modern definition, “figurative sense” as mentioned above or in the original might read:

aftermath | ˈɑːftəmaθ, ˈɑːftəmɑːθ | noun

1 the consequences or after-effects of a significant unpleasant event: food prices soared in the aftermath of the drought.

2 Farming new grass growing after mowing or harvest. ORIGIN late 15th century (in aftermath (sense 2)): from after (as an adjective) + dialect math ‘mowing’, of Germanic origin; related to German Mahd.

(My) Apple Dictionary

I note that the Online Etymology entry suggests the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem so named to further illustrate the meaning of the word, and it does so in a lyrical fashion. The poem (see below) appears to have been first published in 1873, and I make the observation that, in the sense that it combines the agricultural meaning with the figurative idea of change – natural and man-made – and what remains, that Longfellow may have been moved – even subconsciously – by the slaughter upon the battle fields of the Civil War – and its aftermath. (I don’t know this, of course, and probably am influenced by Siegfried Sassoon’s 1919 poem also called “Aftermath”; in which the aftermath in question is that of the First World War – no tepid “gloom” to be found in Sassoon’s poem, rather the stark, bitter reality of war.)

Aftermath

by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

When the summer fields are mown,

When the birds are fledged and flown,

And the dry leaves strew the path;

With the falling of the snow,

With the cawing of the crow,

Once again the fields we mow

And gather in the aftermath.

Not the sweet, new grass with flowers

Is this harvesting of ours;

Not the upland clover bloom;

But the rowen mixed with weeds,

Tangled tufts from marsh and meads,

Where the poppy drops its seeds

In the silence and the gloom.

- Poetry Foundation

There is no need to connect Longfellow with Trench, but I can’t resist. Both were born in the same year and died only a few years apart. Trench (1807-86), for a time Dean of Westminster, is buried in the knave of the Abbey and Longfellow (1807-82) is one of the few Americans, and the first, to have a memorial dedicated in Poet’s Corner at that same venerated place. Whether the pair met during any of Longfellow’s sojourns to Europe I couldn’t say but, even had they, “aftermath” probably didn’t arise in polite conversation, for had it done so Trench would surely have recognized the special characteristic of interest to him and noted it for his scholarly volume; and many, many years later Virginia Woolf’s curiosity could well have been quickly satisfied. Was she ever the wiser? Did she inquire of Leonard or one of her many gentleman (or not so) farmer acquaintances in the home counties?

Though I can find no direct reference, Virginia Woolf’s father would surely have made the acquaintance of Trench – the man. With Longfellow, though, I can make a connection – albeit fleetingly. In Frederic William Maitland’s The Life and Letters of Leslie Stephen (for which Woolf was a source), a note made by the subject for October 7 1863 during an extended Summer in the United States records an encounter (presumably through James Russell Lowell – who would remain a life time friend) in which Stephen describes Longfellow as “a pleasant, white-bearded, benevolent-looking man of very quiet manners, who talked agreeably but not poetically (?) with a want of (the?) readiness (?) which appears to be characteristic of literary gents in these parts …” [p.118]. (Read on a little and one learns Stephen also met Seward and Lincoln – sort of – in Washington! The first did not particularly impress, and the second more than he expected.)

What a rabbit hole did I just fall down!