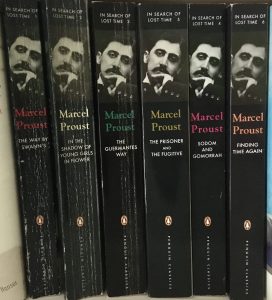

“Was 1925 Literary Modernism’s Most Important Year?” Such is the title of an essay by Ben Libman in the NYT, in which he begins with Virginia Woolf’s rather infamous opinion (The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Volume 2, August 16, 1922) of James Joyce’s Ulysses, and continues to make a case for the literary importance of 1925 over the more often championed 1922 – being the year in which Ulysses and T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land were published. A timely article; for, of course, with the passing of 95 years, on January 1st of this year, works copyrighted in 1925 entered the public domain.

Lidman contends that both as prose and lyric, the two aforesaid works did indeed signify a radical break with literary tradition, but they were also notoriously difficult; allusive, obscure, cantankerous. Ulysses, of course, was just plain notorious, scandalous it has to be said, a matter for the courts (of justice and public opinion).

And in 1925? Four books are published, and without fanfare or legal proceedings or grand ambition, that could be read by the mainstream (or what Woolf may have thought of as her ‘common reader’); Mrs. Dalloway, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, John Dos Passos’ Manhattan Transfer and Ernest Hemingway’s collection of short stories, In Our Time. Libman makes his case well, that it is these works of early modernism that have been, and will remain, the more enduring; for the stylistic innovations they initiated left a lasting legacy and profoundly influenced the literary form.

For Fitzgerald, it is the tool of Symbolism. In the person of Jay Gatsby, he creates a legendary symbol for the transmutation of the American Dream into an American greed and the shattering consequences. How ‘Great’ is it anyway to wallow in the shallow? Dos Passos lays bare a Realism that dared not be, writes as a down and dirty cinéaste might, an editor of the streets of New York; an assembler with the sharpest scissors, cutting bare – only to expose. Or overexpose. He is the town crier, the publicist of the city; a truth-teller and a dissembler, refining the cut and paste long before Word. A fast and furious operator. Then, there is the papa of the modern minimalists; Hemingway saying out loud only that which must be said. What remains after paring back the trees to lay bare the wood? Either it is there to be found, or it’s just not there – or dead. Pay attention to what I say, not what I do not.

And, then, there is Mrs. Woolf, with whom Libman actually begins his argument, and who I quote (in some length; I hope not too much! I hope the link remains live!), because it is important.

[...] As the critic J. Hillis Miller once put it, the reader most often finds that she is “plunged within an individual mind which is being understood from inside by an ubiquitous, all-knowing mind.”

This is evident to us not from the novel’s immortal opening line — “Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself” — but from the one immediately following, which serves as a kind of mirror to the first, tipping us off that we must reread it as something other than objective assertion: “For Lucy had her work cut out for her.” Suddenly, with the lightly colloquial “cut out for her,” we are in the mind not of an omniscient narrator but of a character — Clarissa Dalloway, as the succeeding lines make clear. The reader ceases to think that she is being told what Mrs. Dalloway said about getting the flowers, and begins to think instead that Mrs. Dalloway is just remarking on that fact, as if to herself. And that changes everything.

This narrative technique, known as free-indirect speech, was part of Woolf’s quiet revolution. [...] Woolf perfected this mode, coloring it with the anxiety of modern subjectivity. [...]

[...] we have in “Mrs. Dalloway” the innovation of an enduring, deep structure — something like geometric perspective in painting, that contributes to the development of technique, rather than driving it up a dead end.

- "Was 1925 Literary Modernism's Most Important Year?" by Ben Libman, in the NYT, March 20, 2021

I like Libman’s analysis very much, and I should say he also mentions, and quotes from, Woolf’s 1919 essay, “Modern Fiction” (linked to in my commentary to her diaries) in which, to my mind, though still only hinted of in her own work at that time, she articulates the most succinct case for her evolving literary philosophy and lays the foundation for the direction her writing is about to veer towards.