While half listening to BBC Radio 4 today, and being informed of a virtual service to be led by the Archbishop of Canterbury, I am reminded that today is what is known in the UK as Mothering Sunday. I have taken the time to track down Justin Welby’s sermon – it is not long and the circumstances we face from this wretched pandemic do not have to be explicitly stated to impart a warmth and nearness that contrasts with the coldness and distance that threatens to envelope us. Not surprisingly, Welby advocates seeking consolation in the Church, as a conduit to imparting the same to others, but he also suggests that loving and giving to family and friends, and commitment to our place as a member of a community will in itself offer hope and consolation.

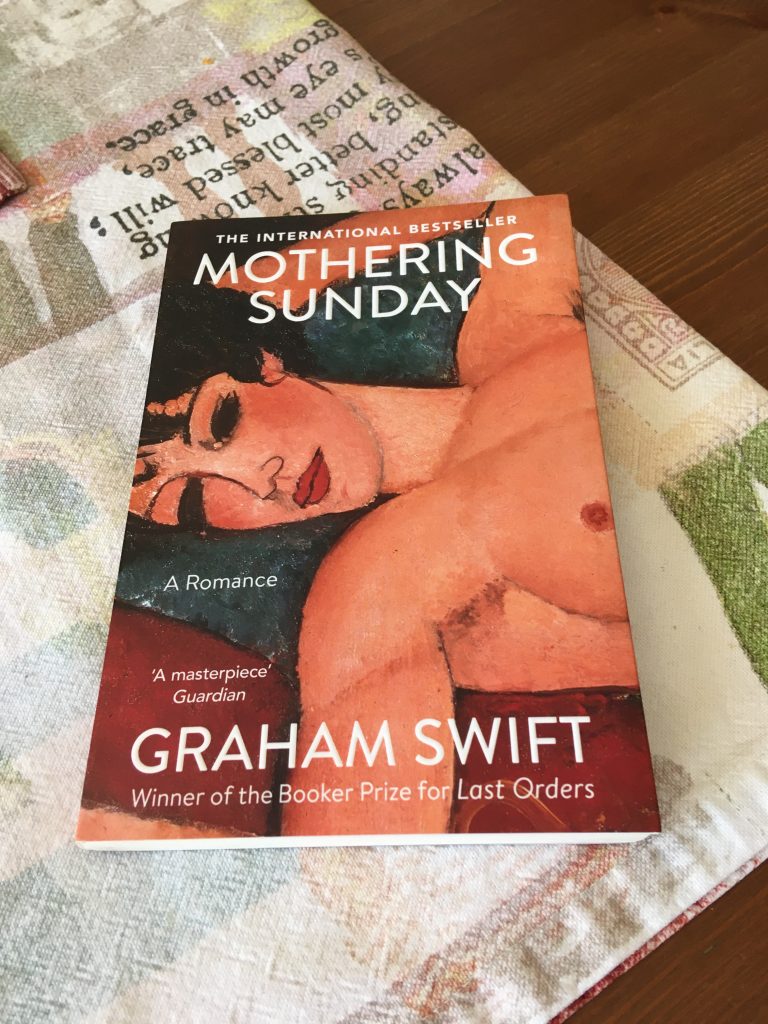

And this day reminds me of the wonderful 2016 work from Graham Swift entitled Mothering Sunday, which I liked so very much – each of the 149 pages! Best described therefore as a novella, an oft maligned and not easy to define genre but the perfect form I think for this gem from Swift.

Not long ago I was contemplating the single day narrative, but I did forget this one, and essentially it is just that, and that day is Mothering Day, 30th March, 1924; diverging only to explain the situation and the perspective from which the narrator speaks. The mood of that day is so beautifully described that it is almost tangible. And startling is Swift’s first person narration – unafraid as he is to choose a woman’s voice; the language, the measure he brings is, to my mind, truly brilliant. To me his work is put together as a Matryoshka doll – a literary form within a literary form, and is illustrative of how a historical moment can define the trajectory of a life, can define literature, can define life, lives …

Subtitled “A romance”; that it is, but more, for it also is a snapshot of British society at that time, when, exacerbated by the trauma and losses of war, the stringent class structures were being stretched and opportunities being created, such that a young woman with brains and ambition had alternatives, places to go beyond servitude.