I recall a piece about Hilary Mantel in The Guardian the other day, which mentioned a forthcoming collection of essays; and I was immediately taken by the title: “Mantel Pieces”. This I thought very clever indeed – a nice play with name in the first instance, and then there is the association to fireplace which extends to frame and flame, warmth and light, kindle and burn, etc., and extended then to the shelf above – a piece, a place of display and decoration. Many attributes that could well apply to a fine piece of writing. And certainly to most everything put to page by Hilary Mantel.

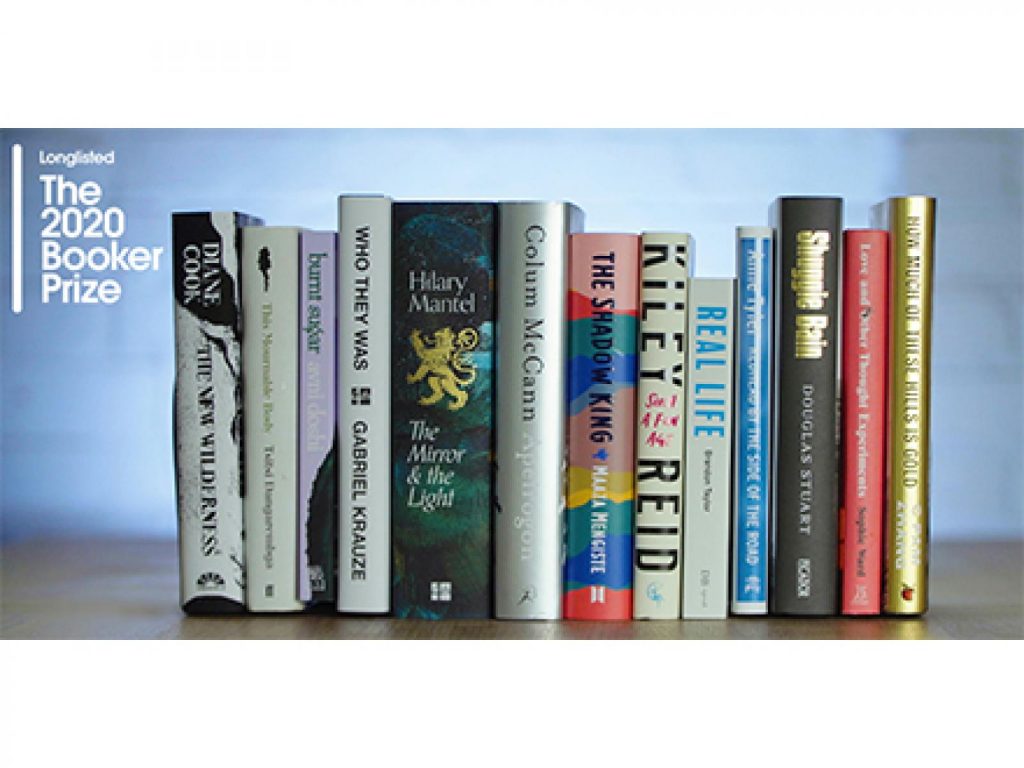

Maybe it was that I was just a little too interested in what Mantel had to say about not making the Booker shortlist (pragmatic and gracious, of course!), or maybe it was not said; for whatever reason I failed to get that the collection does in fact comprise her contributions to the London Review of Books over thirty odd years, and this I register only now on reading this blog entry at the LRB. (A delightfully informative blog entry by the way; fulfilling the requirements as stipulated by the marketing department!) Mantel Pieces, then, is a compilation of twenty essays or reviews and, even more tantalising, each is accompanied by fragments of correspondence (for instance, with the editor Mary-Kay Wilmers) or artwork relating to the piece.

Fact-checking my own recollection: in fact, the subject matter of the collection was NOT said in the abovementioned Guardian article – only the October publication date. What it did say and I should add, is that at the moment Hilary Mantel is busily at work adapting The Mirror and the Light for the stage (alas, there is no mention yet of a continuation to the BBC television effort), and so, even if inclined to, she has little time to cry in her teacups, and obviously maintains an air of optimism in terms of a return to normality in the theatrical landscape in London.

And, diverting slightly, more generally speaking on the politics of book awards, I note the following:

- As I predicted, there does appear again to be murmurings about the probity of opening up of the Booker to US authors (coming mostly from the conservative media in the UK granted), but Hilary Mantel is otherwise inclined and accepts the diversification argument and encourages British and Commonwealth authors to accept the challenge of greater competition. As I said: gracious. I was actually quite peeved, specifically about the Mantel omission and more generally am sceptical of conflating powerful US book market interests with good literature !

- And then, this just read in the NYT, which is illustrative of the above said, and is some affirmation of my argument:

…another major literary event threatens to make an already overcrowded fall publishing season even more chaotic: the release of former President Barack Obama’s memoir, “A Promised Land.”

On Tuesday, the Booker Prize said it was moving its award ceremony, previously scheduled for Nov. 17, to Nov. 19 to avoid overlapping with the publication of Mr. Obama’s book…

…[this]could also fuel new criticism that the prize, originally established in 1969 to honor writers from Commonwealth countries and the Republic of Ireland, has become too Americanized and increasingly focused on the U.S. book market. American authors have dominated the Booker nominees in recent years, following a 2014 rule change that made any novel written in English and published in the U.K. eligible…

It is clear, the book business (and when all’s said and done awards are after all just another element of merchandising) operates on a global scale as with most everything else these days – for good or ill, and that is unlikely to change.

Yes, yes…I get it that the Booker people fear their winner will go under in the Barack Obama hype, it is just that I consider their argument somewhat specious – many, many people will read Obama and a lot, lot less people will read a fine contemporary novel, and some will read both, and maybe I am the latter, but they are hardly works in competition to each other. More honest would have been to admit to kowtowing to the pressure of monolithic publishing companies.

The good news is: in former President Obama, we have an ardent reader, from whom we can expect each summer one of his cult reading lists, which is sure to include National Book Award and Booker nominees and unknown gems and certainly NOT a de rigeur presidential afterlife – granted he has no reason to read a thousand pages of politicking; he lived it to write it!