One hundred years ago, in 1923, Germany was grappling with the instability of the new constitutional republic patched together out of the ashes of a world war and the accompanying chorus of public unrest and grievances – real and imagined; the economy was wracked by reparation payments and hyperinflation; French troops occupied the Rhineland and now the Ruhr valley and a fledgling radical nationalist party in Bavaria (with enough thugs in its midst and an Austrian with a talent for oratory – if you want to call it that – now at its helm) was stirring up resentment and planning (not very well!) a putsch of sorts. Ten years later the events described in Lion Feuchtwanger’s novel “The Oppermans” that I write about below are realized – the failure of the Beer Hall Putsch of 1923 ended in the triumph of the Nazis rise to supremacy and the beginning of some of the darkest days of history.

I knew who Lion Feuchtwanger was. I knew him to be one of the German (and Jewish) literati to get out just in the nick of time. I knew him to be one of those intellectuals to have found safe haven first in the south of France and then in the US; in his case amongst an exile community in Pacific Palisades that included Thomas Mann and Adorno. And that his home, the “Villa Aurora”, exists still – now as an artists residence and a place of cultural exchange and learning.

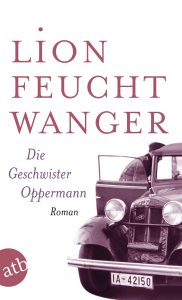

And, until now, I had not read him at all. But, encouraged by a piece written by Joshua Cohen in the NYT last year, that is, in fact, his introduction to a new publication (for which he is apparently responsible for) of the English translation of The Oppermanns, not long ago I sought out and read the most recent German edition entitled Die Geschwister Oppermann. The Geschwister being all the siblings of a privileged and successful German-Jewish family in Berlin: Gustav, a writer of the literary establishment and bon vivant, and the main protagonist from whom the narrative springs, Martin, who runs the family furniture business, Edgar, a brilliant doctor, and Klara, married to a Polish Jew with American passport and the best connections in industry and finance.

As literature in the highest sense of the word, one should not attempt to feign too high a regard. There are portions that have been written very carelessly indeed, without an editorial eye and committed revision – inconsistencies, repetitions, messy dialogue abound. Short sentences are fine, but only up to a point. And when one too often wonders whether that sentence – or something not dissimilar – has not previously been read – and it has? That Feuchtwanger was operating in screen-writing mode (as suggested by Cohen and elsewhere) is a good explanation for the often disjointed form; one which may very well work in drafting, with a camera at the fore, a curt: cut to … and a continuity ‘girl’ at one’s beck and call. It may also account for what I thought the exaggerated, often repetitive, descriptive passages. Though I did wonder, also, whether here was not a style characteristic of a lot of German writers of this generation who, unlike Thomas Mann and few others, didn’t have the luxury of working alone for literary publication, but had to also shuffle between theater, film, journalism, perhaps, academia.

And that is where one gets to why this book is special, and its shortcomings so easily forgiven. Feuchtwanger is not a stylist, absolutely no Th. Mann, but style here is not the point. Literary inadequacies in form are hardly to be wondered at considering the circumstances and urgency under which this novel came to be. Writing, as Cohen says, in “real time”, Feuchtwanger’s novel is the only work that I have read that so portrays – in narrative form, and as it happens – the end game in the Nazis diabolical rise to power, and being played out against the backdrop of an already fractured German society – many elements of which were willing or passive participants.

And I mean the collapse of an entire society – its laws, its norms, its moral fabric. Only in retrospect may one presume that here was a disintegration just waiting to happen. From its beginnings in late 1932 as Gustav celebrates his 50th birthday at his Grunewald villa with family and friends, the novel is bound to the chronology of events leading to the Machtergreifung in January 1933 and what happened next – in Berlin (knowing well enough the particular topography in western Berlin that the novel traverses, added an extra impetus to my reading and its reception), in the provinces, in and out of exile. That that city which has so flourished in these last decades as I write, just as it had so embraced modernity and all its hallmarks of tolerance and indulgence a century ago whilst chaos reigned on the streets and in all the institutions of the young Weimar Republic, could have degenerated so swiftly is a potent reminder of, not just the inherent fragility of almost all social structures, but also the prejudices they conceal and opportunism they encourage.

A tragic tale, a cautionary tale for the ages. Irrespective of its deficits, The Oppermans is an important and immensely disturbing book that should be read for its exposition of the lies told – and those we tell ourselves still – and where they ultimately lead.