There are names in journalism that everyone knows – Janet Malcolm, who died on June 16 in New York City at 86 years of age, is one such. During her almost sixty years at The New Yorker, she wrote a multitude of pieces over an extraordinary range; some I have read but most I of course I have not – being (funnily enough!) once too young, and later, before the digital revolution, while the said esteemed publication came my way only sporadically.

Interesting, are the controversies commented on in The New York Times obituary – serving to remind of just how radically the print media and journalism has changed in the last decades – how trite Malcolm’s transgressions now appear and how prescient her ideas about what good journalism is and what it could and could not do.

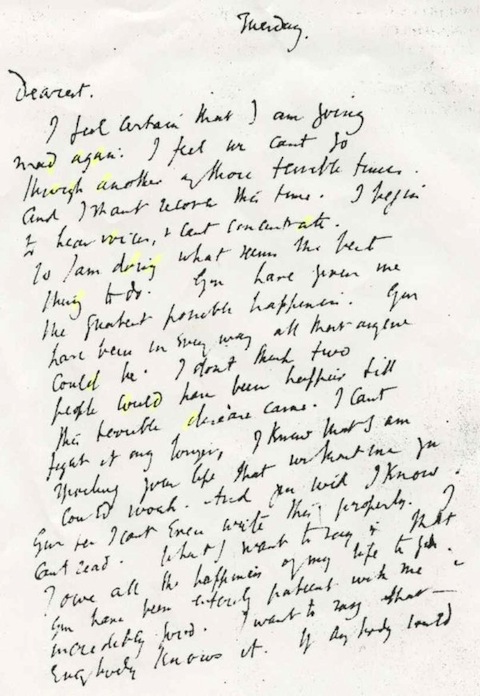

Also, in the NYT obit, and as one forever on the watch for lurking wolves – hunting in pack for easy prey, with family in tow or home in the den – I note with delight the link to her great 1995 essay in The New Yorker; entitled “A House of One’s Own” and inspired by the Stephen/Woolf/Bell family house-hopping, correspondence and biographical works, including Quentin Bell’s famous Woolf biography, and culminating with conversations with Quentin and Anne Olivier Bell during a visit of her own to Vanessa’s Charleston home. Malcolm brilliantly explores the Stephen sisters’ coming of age and complicated relationship; with others and with each other and brings Vanessa out of the shadow of her more famous sister. She surprises with details of the familial animosities and inconsistencies that the protagonists left in their wake for the next generation to grapple with. But, in considering Angelica Bell’s bitter recriminations, what Malcolm also does in this essay is articulate her own personal theory of biography; one in which choices have to be made, circumstances rarely prevail and moral certitude anything but.

In what I have written, […]I have, like every other biographer, conveniently forgotten that I am not writing a novel, and that it really isn’t for me to say who is good and who is bad, who is noble and who is faintly ridiculous. Life is infinitely less orderly and more bafflingly ambiguous than any novel, […]and if we pause to remember that [they] were actual, multidimensional individuals, whose parents loved them and whose lives were of inestimable preciousness to themselves, we have to face the problem that every biographer faces and none can solve; namely, that he is standing in quicksand as he writes. There is no floor under his enterprise, no basis for moral certainty. Every character in a biography contains within himself or herself the potential for a reverse image. The finding of a new cache of letters, the stepping forward of a new witness, the coming into fashion of a new ideology—all these events, and particularly the last one, can destabilize any biographical configuration, overturn any biographical consensus, transform any good character into a bad one, and vice versa. […] Another biographer might have made—as a subsequent biographer may well make—a different choice. The distinguished dead are clay in the hands of writers, and chance determines the shapes that their actions and characters assume in the books written about them.

Janet Malcolm in The New Yorker A Critic at Large – June 5, 1995 Issue

Finally, The New York Review of Books, to whom Janet Malcolm also often contributed over very many years, kindly provide a peep into their archives (probably for a limited time) to celebrate a great journalist’s life. From their mail of June 17, 2021:

Free from the Archives: Janet Malcolm, a longtime contributor to The New York Review, died yesterday at the age of eighty-six. Between 1981 and 2020, Malcolm published thirty-eight pieces in our pages, including the essay below, part of her career-long meditation on the hazards of writing about other people. “Almost from the start,” she writes, “I was struck by the unhealthiness of the journalist-subject relationship, and every piece I wrote only deepened my consciousness of the canker that lies at the heart of the rose of journalism.” The Morality of Journalism There is no such thing as a work of pure factuality, any more than there is one of pure fictitiousness. As every work of fiction draws on life, so every work of nonfiction draws on art.

25 June 2021: There have been numerous tributes to Janet Malcolm in the last days, but I would just like to mention one last one; an antipodean perspective that unites her with another that I have long, long, admired. Should one have read any of Helen Garner’s non-fiction works, it would surely not surprise that she would have been influenced by Malcolm, in style, in sensibility and in methodology. (It also should be said, both writers shared a talent for attracting controversy, and not shying from it, and that Malcolm was not uncritical of Garner on a book and its repercussions that received intense scrutiny in the Australian literary scene and beyond, and that this appears not to have affected Garner’s admiration.) Here in a Guardian tribute adapted from her introduction to the Australian publication of an essay collection entitled “Forty-One False Starts“, Garner says:

To open any one of her books at random is to find myself drawn back into that unmistakable sensibility, that unique tissue of mind, and to grasp how deeply I am indebted to her. […]

[…]I saw manifest [in her Plath biography,The Silent Woman] what I was at the time painfully trying to learn: the fact that beneath the thick layers of a writer’s self-censorship, of her fear of being boring or wrong, lies a whole humming, seething world waiting to be released. I learned from watching Malcolm in full flight that I could go much further than timidly nibbling at the edges of people’s peculiar behaviour. I saw that I could get a grip on it and dare to interpret it, to coax meaning from it. The tools were already in my possession. […] that in journalism, as well as in fiction, I could call upon the imagery, the spontaneous associations and the emblematic objects that I had learned to trust when I myself was groaning on the therapist’s couch.

Helen Garner on Janet Malcolm: ‘Her writing turns us into better readers’, The Guardian, June 24th 2021.