In the last days, I have savoured the theatrical treat (via YouTube livestream) of Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller alternating as Victor Frankenstein and his monster creation (a tour de force by both as both in my opinion!) in Danny Boyle’s 2011 National Theatre (UK) adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. (Here is Michael Billington’s original Guardian review.) Without this pest that is upon us, would such a privilege be granted? Perhaps not. You see, I do look for things positive [sic] to take from this crisis.

Firstly, as I have previously stated, I am interested in the process of adaptation from one medium to another, and in this instance it works very well indeed; perhaps, because the reduced plot form (for instance, the omission of the framed narrative) and character tableau does not mitigate the precepts of rationalist thought and the limitations of science being explored in the original work, nor the questions posed of the conflict between the enlightened individual and a humane social order. As with the novel, this stage version can be best appreciated as a composite – as a philosophical treatise masquerading as an entertainment in a gothic tradition.

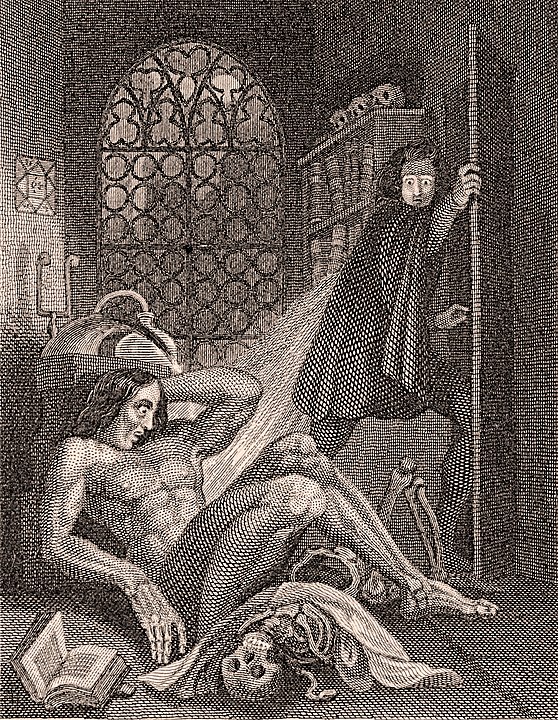

On reflection, I must also say that Shelley’s classic tale first published anonymously in 1818 as Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (the Prometheus additive being particularly telling), captivates still, and when considering a range of Lektüre for these daunting days, it is one, with its relativisation of our place in the greater natural order of things, that is well worth returning to. Not to mention, it being just a wonderfully well told story!