The Journey Begins

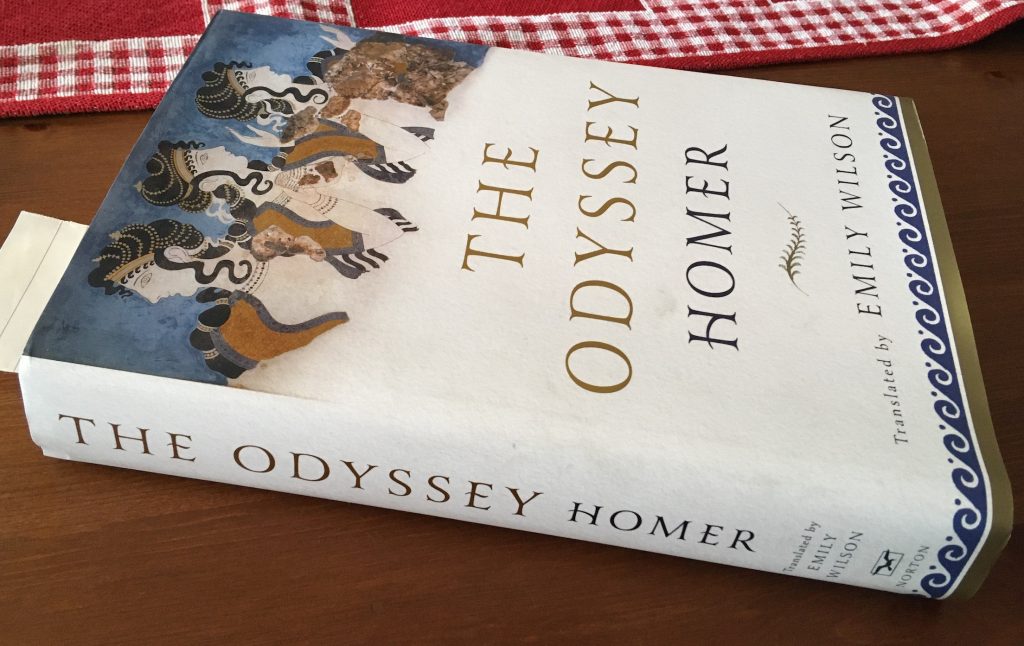

Firstly, Homer, I have now concluded, is meant to be read aloud. Browsing and rereading passages is one thing, but to capture the rhythm and maintain concentration one must, absolutely must, emote! So that is precisely what I am doing in video chunks of a maximum of fifteen minutes – privately I should say. Being unsure sometimes of a correct pronunciation, I have found the comprehensive glossary with pronunciation key at the back of Wilson’s book [pp. 553-577] to be very helpful, and as a last resort a “how to pronounce…” request to Google has an answer every time. And, it is not cheating to refer to the Notes, including summary paragraph! [pp. 527-552]

To also be said, English translations of The Odyssey have named each of the twenty-four sections variously: “Song”, “Rhapsody”, “Scroll”, “Chapter” or, as Emily Wilson like other translators has chosen to do, simply “Book”. Further, she gives each of the books a title, which, if not unique, seems at the very least to be unusual, and I think a really nice touch – adding to the work’s order and accessibility.

Book 1: The Boy and the Goddess

pp. 105-119

This most famous of epic journeys does not begin with an actual journey, nor with the hero, the principal journeyer, rather in medias res at the point in which Athena intervenes, sanctioned by the will of Zeus, upon the woes of her favoured one, Odysseus, to facilitate his homecoming. Under the guise of Mentes and familial friendship, Athena infiltrates the chaotic Ithaca household of Odysseus’ wife Penelope and son Telemachus, overrun as it is by bawdy, avaricious suitors, and with all her wiles and powers of persuasion sets the path Telemachus will follow on a journey of his own – a journey in search of the absent father and in a wider sense a journey to manhood.

Book 2: A Dangerous Journey

pp. 120-134

But before his journey is to begin, Telemachus must bring his case to the Ithacans – and the suitors. One of the suitors, Antinous, reveals Penelope’s trick of the never finished burial sheet for Laertes – weaving by day and surreptitiously unweaving by night. Zeus sends down swooping eagles, but the prophecy foretold by one is not heeded. Telemachus shows his stuff and faces down the suitor’s taunts, but again it is only with the divine help of Athena that a ship and crew is procured – and the earthly loyalty of his old nurse Eurycleia in keeping his secret safe and gathering together the rations required. Under the guidance of Athena (guised as Mentor), and the winds and seas under her control, the curved ship sets sail.