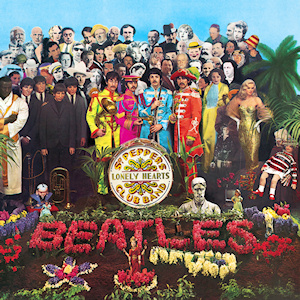

the lonely hearts club…

Covid-19 knows not social status, not race nor creed, nor national borders. We are in this together -or so we are told. (Do I alone wonder at the limits of our proclaimed solidarity?) And amidst these strangest of days in which we have been hurtled, many of us may wonder at the times ahead – how long? what to do? – we ponder philosophical and political questions on freedoms and responsibilites – individual and collective, reappraised is the role of the oft maligned State, and we even look beyond: at the “who we are” that comes out when it’s all said and done. More than anything we contemplate what this will be like, this “staying at home”, this “minimising social interaction”. Olivia Lange writing on ‘How to Be Lonely’ at The New York Times, offers her thoughts, and some from Virginia Woolf:

But loneliness isn’t just a negative state, to be vanquished or suppressed. There’s a magical aspect to it too, an intensifying of perception that led Virginia Woolf to write in her diary of 1929: “If I could catch the feeling, I would: the feeling of the singing of the real world, as one is driven by loneliness and silence from the habitable world.” Woolf was no stranger to quarantine. Confined to a sickbed for long periods, she saw something thrilling in loneliness, a state of lack and longing that can be intensely creative.

The New York Times, Opinion, March 19 2020

To put this a little more in context, the Woolf quote is part of a lengthy and fragmented diary entry on Friday 11 October 1929; finding herself “surrounded with silence”, not in a physical sense but what she refers to as a pervasive “inner loneliness”. Reflecting on all her personal and professional good fortunes, the triumphs of family and friends, she wonders at the disquiet that haunts her, and which she can not quite grasp; but this time at least she will “Fight, fight. If I could catch the feeling…”

And as Virginia Woolf fought (for most of her life & until she could no more) the demon lurking in her head, guised as an empty void, so then should we all give it a go – be creative; find new ways of occupying ourselves, of communicating, of sharing not only our anxieties but also little kindnesses, and be patient and alert not only to our own needs but those of others. And, as Laing says at the end of her piece:

Love is not just conveyed by touch. It moves between strangers; it travels through objects and words in books. There are so many things available to sustain us now, and though it sounds counterintuitive to say it, loneliness is one of them. The weird gift of loneliness is that it grounds us in our common humanity. Other people have been afraid, waited, listened for news. Other people have survived. The whole world is in the same boat. However frightened we may feel, we have never been less alone.

The New York Times, Opinion, March 19 2020

And I would add – a good dose of well placed humour. Returning to Virginia Woolf – often overlooked in any short telling focusing on the scathingly brilliant and problematic personality legend would have us believe, is that Woolf often displayed, and especially in her diaries and private correspondence, an abundance of humour and warmth, an appreciation of human frailty and no mean measure of self-deprecation. Some laughter and an awareness of the very smallness of ourselves and greater humanity in the continuum of history may help placate our fears. And a recognition that more likely than not there are many who are a whole lot worse off than ourselves.

And music – personal comfort music for when times are tough, and that for me always includes the Beatles.