By September 1928, Virginia is beginning to feel that the summer has seen too much society and not enough solitude. Entertaining Leonard’s mother is a hardship and brings forth a tirade on the many failings of the “Jewess” and mothers in general [p.195] and this one in particular, but also her own peculiar imagining of the tyranny of motherhood. Or is it regret she feels? That her mother had died when she was so young? Or that she didn’t have a child? During September, there are interactions with, amongst others, Desmond MacCarthy, the Bagenals, Dottie Wellesley again (which didn’t go well, so enraged was Leonard, see VW Letters Vol. 3. no. 1922 to Vita), the Keyneses, and by 22nd September VW is becoming increasingly agitated by her impending holiday in France with Vita: “[…] 7 days alone with Vita: interested; excited, but afraid – she may find me out, I her out. […]” [p. 197]

The editorial note is informative in a number of respects, and so I shall summarise it in length. On Monday 24 September Virginia and Vita sailed from Newhaven and spent a week in Burgundy (see VW Letters Vol. 3 letters nos. 1926-32 written to Leonard) before returning to England on 1st October. On 4 October, the Woolfs lunched with Vita at Long Barn en route to London. Orlando was published on 11th October. On 2o October they went to Cambridge, where VW read a paper to the Arts Society at Newnham College, staying the night with Pernel Strachey, the college principal. They also lunched with Dadie Rylands. The following week Virginia again went to Cambridge – this time with Vita – and spoke to the student society ODTAA at Girton College on 26 October. These two papers on ‘Women and Fiction’ she would expand and publish a year later as A Room of One’s Own (the lunch with Rylands finding its way into the final text!)

Back to her diary on Saturday 27 October, Virginia bemoans the time passing (observing from the metaphorical bridge – and vividly describing – the flowing waters). With Summer gone, Orlando published and the trip to Burgundy with Vita behind her – “We did not find each other out” [p.199] – she is anxious to put her head down and get back to work. Sales and reviews of Orlando are pleasing and she can only scoff at J.C. Squire’s more than back-handed compliments (Observer 21 October 1928) of ‘a very pleasant trifle [that would] entertain the drawing-rooms for an hour’ [footnote p. 200].

The only original review I can find of Orlando is from The New York Times of October 21st (NYT archive). It is neither fawning, nor disparaging, but respectful and thoughtful. Virginia Woolf obviously interests the reviewer, a certain Cleveland B. Chase – which can not be said of the abovementioned ‘squire’ with whom Vita, at least, is adamant she will never speak to again (see letter from Vita Sackville-West to VW dated 21st October 1928)- and he is alert to and interested in the intellectual endeavors and experimentation she is pursuing in her writing.

Virginia feigns (?) relief that [the] long toil at the women’s lecture […] at Girton […] [p.200] has found its end, but she does spend some time reflecting on her Cambridge visit; the young women that she met; their earnestness, their intelligence – and the few opportunities that will come their way, irrespective of their aspirations and endeavors! And of her own regret at the narrowness of her own experience (as she sees it). Dining with Mary Hutch. leads to visiting Eliot who reads a draft of Ash Wednesday; VW’s opinion of the poem she does not divulge here, but given her irritation at his overly zealous conversion to Anglicanism …

Wednesday 7 November: Even if she is, as she states, “headachy, & dimly obscured with sleeping draught” [p.201] in the aftermath (a word of interest! see this blog post or the embed below in desktop version) of Orlando, still, Virginia manages a long, amusing entry. She muses at the dullness of the upper, moneyed classes – Cunards, Colefaxes (again!), Donegall/Chichesters – they all get their comeuppance. As usual only Vita is spared.

With Orlando done, Virginia ponders her next literary adventure. Congratulating herself on what she has achieved in the process (of writing Orlando) – directness, continuity, holding reality at bay with fantastic and fanciful narrative. Enamored now it seems with this new way of (re-) writing history, she considers whether this method can be used for a history of “Newnham or the woman’s movement” [p.203] – an indication of how inspiring she found her visit to the Cambridge colleges. And then in the same breath she recalls “The Moths” – a totally different matter; an exercise in the abstract, a pursuit of a mystical essence. She is thinking a lot about “style”.

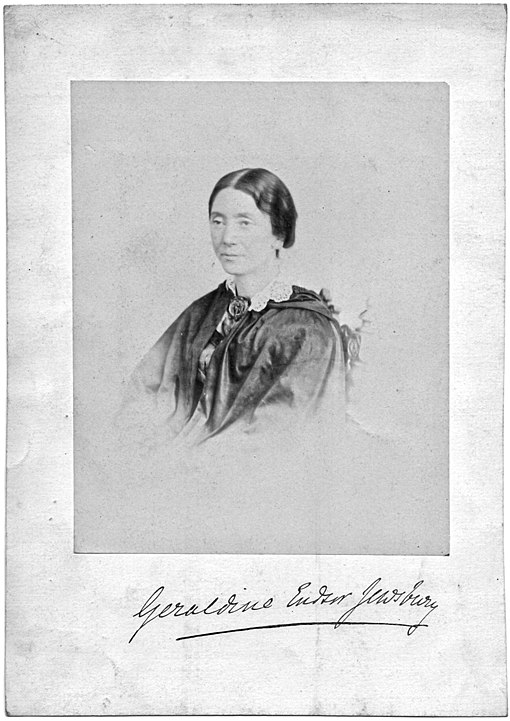

On Saturday 10th November Virginia tells us she should be otherwise occupied – like reading Jewsbury (in preparation for her article “Geraldine and Jane” pub. in the TLS on 28 February 1929) – but is mildly disconcerted as to which of her critics – Bennett or Squires – is most abusive of her (in respect to Orlando), and then very taken up with the continuance of the obscenity case against Radclyffe Hall’s novel (see entry on 8th August) which she had attended the previous day, speaking in passing with Hall’s lover Lady Una Troubridge with whom she was briefly acquainted as a child in Kensington. She seemed to enjoy the “humbug” and “ceremony” of the whole affair, and was relieved that they (writers, artists) were deemed irrelevant – they are after all (in her opinion) experts on art not obscenity.

On 25th November they are at Rodmell for Leonard’s 48th birthday and on 28th November back in London and after one of their “apparently successful” evenings (with Adrian, Clive, Lytton, Vita et.al), Virginia remembers this day that would have been her father’s 96th birthday. And, more importantly, she wonders what on earth would have become of her had he lived longer – certainly there would have been no writing, no books, not this life that she now has and (mostly) enjoys. She reflects on her previous “unhealthy” obsession with her parents and how writing “Lighthouse” helped her move on.

Virginia is disparaging of Lytton’s Elizabeth and Essex – “bad” she says, though others have praised it, and in the next breath reflects on her mean-spiritedness and whether that comes from an innately jealous personae. (Or, I would suggest, is it just her intellectual honesty when it comes to the written word? An honesty that transcends friendship?) Questions of literary form and style are constantly on her mind, and specifically the bringing together of all those floating, fleeting ideas to do with “The Moths” which have increasingly preoccupied her since finishing Orlando, and inspired by what the writing of Orlando has taught her. How to fuse the external world with the internal, ‘real’ prose with all the vagaries and textures of poetry.

As December 1928 draws on, social events mostly irritate, society is immersed by news of the ailing King George V and the impending Christmas. The formidable Lady Strachey dies on 15 December and VW writes the eulogy for The Nation and Athenaeum (reprinted in Books and Portraits, 1977). Orlando is selling brilliantly, and Virginia is spending money on herself – for the first time she says; jewellery, carpets. She exalts in just having the sheer freedom to spend! She dines with Ethel Sands and meets Max Beerbohm and with the Hutchinsons and met George Moore. Woolf gives some time to describing them both, and placing them within the realm of ‘the greats’ – but she […doesn’t] find much difference between the great & ourselves […]. One notes, I note, Beerbohm has ‘plump firm’ hands and Moore ‘little flipper’ ones. It seems to me Woolf’s preference lay with the former. [pp.213-214]