Returning to Hogarth on New Year’s Day 1924, a new book was duly begun on 3 January 1924, and which includes “an improvement” in the form of a calendar for the first three months of the year (explained on 12th January.)

DIARY XIiI: 3 january 1924-6 january 1925

Hogarth House, Richmond.

From this day forward I will always look forward to a new year that “is almost certainly bound to be the most eventful…”, which it will almost certainly bound to be NOT! But so starts Virginia Woolf her diary on Thursday 3 January, 1924. And she does almost immediately question her own sense of optimism! There still is the matter of finding a house, sorting out (again!) the servant problems, writing, publishing, making money. “All is possibility and doubt” she says, and just that may any one of us conclude should we dare a look into the future.

But Woolf’s optimism does not seem to have been misplaced when on Wednesday 9 January she proudly reports:

At this very moment, or fifteen minutes ago, to be precise, I bought the ten years lease of 52 Tavistock Squre London W.C.1-I like writing Tavistock…the house is ours: & the basement, & the billiard room, with the rock garden on top, & the view of the square in front & the desolated buildings behind, & Southhampton Row, & the whole of London…

Vol. 2 [pp. 282-283]

The joys of which she then waxes lyrical! Finally, back to the city she loves, after these years of exile forced upon her by the guardians of her constitution. But she doesn’t forget words of gratitude for Richmond and Hogarth – that offered sanctuary from her own madness, and that of the war. And only there, perhaps, could she and Leonard have dared their precarious venture into the press and publishing. Memories from the last decade flood her – of the living: all the people who have come and gone, conversations had, plans made; and of the dead: visions had and voices heard.

After major and minor glitches and contractual shenanigans during January, Virginia visited the solicitors on Wednesday, 23rd January, and handed over a cheque and signature, and 52 Tavistock Squre was now well on its way to becoming the Woolf’s new London home, and on Sunday, 3rd February she says “the house presumably ours tomorrow. So I shall have a room of my own to sit down in, after almost 10 years, in London.” [p. 291] I note, that on matters pertaining to property it is Mrs. Woolf who takes the initiative, and Mr. Woolf conspicuous by his absence, but I am certain not disinterest. On this day, too, she mentions (what a footnote says to be) her first meeting with Arnold Bennett – whilst their respective theories of fictional writing may differ, VW describes him personally not unfavourably (19 June 1923, above).

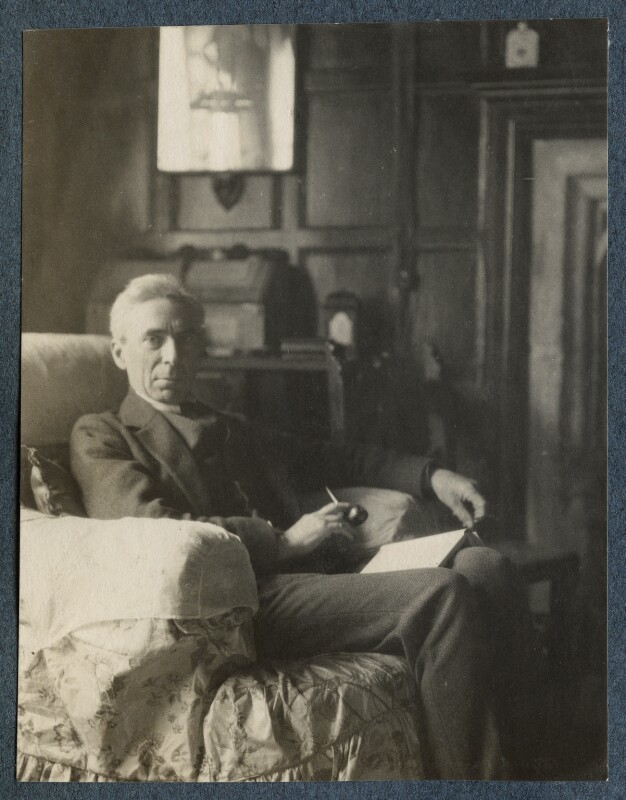

Meanwhile, essays are being accepted in various publications – on Austen, Montaigne, for instance (that both also find their way into The Common Reader), and she returns always to “The Hours” as it is still titled. Morgan reveals that he has completed his novel (A Passage to India) and they (the Woolfs) are the first to know. On 23 February she “quotes” in length “the celebrated Mr. Russell” (Bertrand Russell) encountered a few evenings previously at Karin’s (Russell had been married to her aunt, Alys Pearsall Smith) – on his cancer (not known to the interlocutors: Russell would live for another forty odd years!), his new found optimism and love of life, on philosophers, poets and family. Whether VW got this all right, who knows, but a very entertaining interlude anyway. [pp. 293-295] I swear, those guys unloaded to her, they really did! And she? What thinks she of this towering intellect of the 20th century? True to form, she doesn’t allow her undoubted awe of Russell’s cerebral qualities to get in the way of her incisive, personal appraisal.

One does not like him. Yet he is brilliant of course […] outspoken; familiar; likes people; & yet & yet – He disapproves of me perhaps? He has not much body of character […his mind seems] attached to a flimsy little car […] His adventures with his wives diminish his importance […] no chin & he is dapper. Nevertheless, I should like the run of of his headpiece.

Vol 2. [p 295]

Wednesday 12 March 1924: “And I am now going to write the very last pages ever to be written at Hogarth House…” [p.295] First the weather, then her “stuffy and heavy” head, then the night before (dinner for Edmund Blunden at the Florence Restaurant in Rupert Street) and an altercation of sorts with Murry that started with her “exquisite sensibilities”; alas, the specifics neglected in her retelling, and transgressed to George Moore’s recent criticism of Hardy which Murry finds more than lamentable and Leonard considers hardly surprising. They part, and not well, and the Woolfs make the “long cold exhausting journey [back to Richmond] for the last time” [p.297].

The editor’s note on p. 297, tells us that on 13-14 March 1924 the Woolfs moved from Richmond to 52 Tavistock Square in Bloomsbury. They stayed overnight on the 14th at Clive’s in Gordon Square, and first slept in their new home on Saturday 15 March.

Further, their new living situation is more clearly described. The Woolfs occupied the two top floors of the large four-story house on the south side of the square. The Hogarth Press was in the basement, and a large billiard room built in the back garden was converted into a study for VW and storage space for Hogarth books. A firm of solicitors occupied the ground and first floors.

52 Tavistock Square, Bloomsbury, London.

Few pictures of the Woolf’s home and premier place of work during this period remain; 52 Tavistock was destroyed during the Blitz on Wednesday 16th October, 1941, only a year after the Woolfs had relocated to larger premises in Mecklenburgh Square (and had been unable to unload their lease on Tavistock). But here are two excerpts from Hermione Lee’s biography of Woolf, which may conjure a sense of the look and feel of a place very many people wanted to visit – and it be known that they did so. Such had their celebrity grown. In respect to the second extract, with its interior description, the three panels by Vanessa and Duncan referred to, were in fact retrieved from the remains by Virginia a couple of weeks after it was bombed. At the end of 1924, they had been featured in this article about modern design for Vogue.

People went, in great numbers, to the house in Tavistock Square in various states of eagerness and apprehension […] People coming or working there took a vivid impression from it, particularly because of its double and divided nature, the basement for work, the upstairs flat for entertaining. The basement life […was] a curious mixture of the ramshackle and the orderly. The Press office at the front of the basement (with the printing room – the treadle machine, the compositor’s stone and all the type – in a disused scullery behind it) was divided by a door and a long stone corridor from the huge, sparsely furnished, windowless room at the back, once a billiards room, with a skylight and a rather dim underwater feeling to it.

Hermione Lee ” Virginia Woolf “ Ch. 31. Random House. Kindle Edition.

The rooms of the Woolfs’ two floors, looking out on to the high trees of Tavistock Square and the churches and buildings beyond, were light and colourful and pretty and Mediterranean-looking, full of books and papers; they looked like the covers of her books. Everyone was struck by the three huge panels which Vanessa and Duncan had painted when the Woolfs first moved in, in reds and browns and blues, each presenting a domestic tableau in a roundel, within a frame of crosshatching: the table and jug and scroll of paper on the left, the piano and guitar in the centre, the bowl of flowers, fan, open book and mandolin on the right. […] It was not a grand or glossy setting, but it had a strong, idiosyncratic, seductive atmosphere. Everyone who sat in the dining-room for tea (honey from Monk’s House) or for supper under soft lamp-light, and then in the large drawing-room over the fire, with the dogs, the cigarette smoke, the talk, took away an image of Virginia Woolf.

Hermione Lee ” Virginia Woolf “ Ch. 31. Random House. Kindle Edition.

Saturday 5 April: With the exception of the noise from the streets, the return to London has lived up to Virginia’s expectations – the wonderful convenience, the life and bustle, and she wonders why it is she finds it so very lovely when it is, after all, “stony hearted, & callous”. This entry runs then mid-line into Tuesday, April 15th, and Leonard grumbling that he has not done any work since they moved to London. Then there is the bizarre accident that seems absolutely not, even nearly, to have killed Angelica. [p. 299] And, “the habit of living” in their new home is beginning to form, and the city noises becoming less irritating. She is settling in.

On Monday 5th May, after returning from an Easter sojourn in Rodmell, VW remembers her mother’s death twenty-nine years previously. One believes her when she says she absolutely remembers that day and that thirteen-year-old self, rather, more precisely, she suggests them to be “impressions” that are etched deeply and indelibly in her memory. Returning again from Rodmell on Monday 26th May [footnote p. 301], she contemplates the different effects city and country have upon her, and does some professional planning through to the next year to bring to an end “The Hours” and her essays. [The footnote p. 301 confirms her adherence – The Common Reader published in April, 1925, and Mrs. Dalloway in May.] At the end of the entry, Woolf confesses to not having indulged in, nor dissected, the society fun and games of the last month or so – at Rodmell, Cambridge, Tidmarsh. She does though have time to observe, and not for the first time, how very off-putting Eliot has become – “sinister & pedagogic”, “a queer figure”. [p.302]

Returning after Whitsun again from a stay in Rodmell, the rest of June and July is spent in states variously drowsy and industrious. Dadie joins them now at the Press, and Marjorie becomes ill, so there are a multitude of adjustments to be made. Visits locally – with Clive, the Stracheys – and further afield – to Garsington. To the famous (and sprawling) “Knole”, and the Sackvilles – for the first time? And motoring through Kent with Vita and Harold, with Geoffrey Scott and Dorothy Wellesley in tow. And feeling very class-conscious indeed. [pp.306-307]. The 30th July sees the Woolfs return again to Monks House, where they were to mostly remain for the rest of the summer.

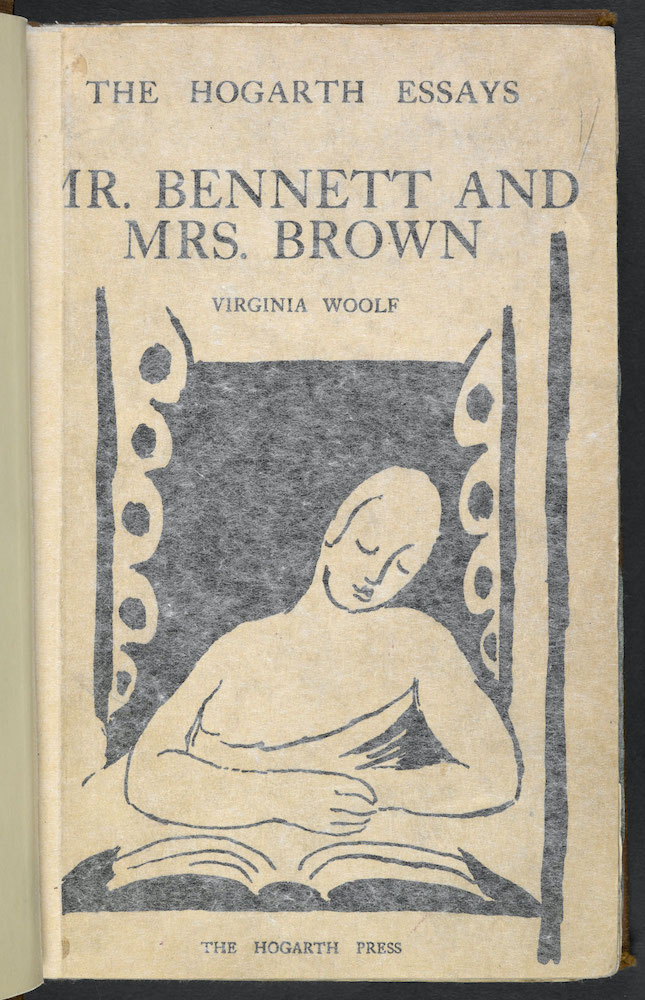

Following the death of Joseph Conrad, the TLS makes a hasty request on 15th August for an essay; to which she obliged, but then can’t help but mention a certain TLS columnist, A.B. Walkley, whose contribution to the ongoing ‘character vs. plot’, ‘when emotion must be, then how much is too much or just enough…’ etcetera, started by Bennett, and to which Woolf has responded in a piece first read at the Cambridge Heretics in May, then published in the Criterion in July and to be published by Hogarth as a pamphlet in October. Renowned, of course, to this day as Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown – Woolf’s brilliant and idiosyncratic defense of modernity (with her much quoted assertion that “…on or about December 1910 human character changed”) and caustic put-down of the traditionalists.

Mrs. Dalloway is so much on her mind (on the 2nd August she was dealing with the death of Septimus Smith), that when the Keynes came to tea at Monk House on 9th August, she confesses to calling Lydia “Rezia by mistake” [p.310]

Back in Tavistock Square at the beginning of October, the last words of Mrs. Dalloway have been written: “For there she was.” (I double check, and these final words remained unaltered.) This, VW says, was on 8th October, and is self-congratulatory of her feat in bringing it to an end in only a year or so and, more importantly, without the interruption of illness. She knows this novel is good. She says her house is now perfect. All is well. But then her mind wanders to the ghost of Katherine Mansfield. Why? (I imagine she wants to dangle “Mrs. Dalloway” before K., and demand of her : what she thinks, whether she could have done as well.) What Woolf does say, and wants to believe, is that even if Mansfield was alive and writing, it would be she (Woolf) considered “the more gifted”. And, then again that pervading regret that haunts her: “…K. & I had our relationship; & never again shall I have one like it.”[p.317].

Saturday 13 December: Just when Woolf was becoming comfortable with his presence, Dadie Rylands decides he must leave Hogarth (his Cambridge dissertation must take precedent), and his friend, Angus Davidson, suggested as his successor. Away from the Press, she is conscientiously retyping Mrs. Dalloway and remains delighted with her accomplishment.

Monday 21 December: Virginia Woolf refers back to January 3rd, and sees the year to be every bit as eventful as she had prophesied, and expectations fulfilled. They are in London, with Nelly only, the household complete. Granted, Dadie has come and gone at the Press, but in Angus they have a replacement. Mrs. D. & the Common Reader are almost ready to be sent out into the world. On matters of fame & money – Clive’s long article is out in The Dial, with £50 from Harper’s, the days of begging were gone, for she and Leonard both. Friendships flourish, and the Press a reprieve from the emotional labor of writing, and a magnet for all sorts who come and go – to see, to be seen with the Woolves at work. Last words of the year: “This afternoon they cut down the tree at the back: the tree I used to see from my basement skylight”

Editor’s note [p.327]: On Christmas Eve, taking Angus Davidson with them, the Woolfs went to Monks House. The Woolf and Bell households did not meet; the weather was appalling, and the River Ouse overflowed its banks.

Here ends Volume Two (1920 -1924) of The Diary of Virginia Woolf, and is continued in Volume Three covering the years 1925-1930.

Last updated: December 29th, 2020. [II VW Diary, 21 December 1924 p.327]