diary xvi: 3 February 1927-22 December 1927

“Fate always contrives that I begin the new year in February.” [p.125] So Virginia Woolf begins this book on Thursday 3 February, and goes on to bemoan that the book is a block, aghast that she may die first and Leonard would read these words of hers, and are they of any interest anyway, and that her handwriting deteriorates. But perks up to say “[…] I shall write my memoirs out of them, one of these days.” [p.125]. She reports of an overnight visit with the Webbs on 28th January; one which she found “strenuous”, but (from the footnote) Beatrice Webb’s diary note to the occasion is positive in tone; referring to the Woolfs as an “exceptionally gifted pair”. On the 12 February she wonders at the demise of the relationship between Clive and Mary, and his intent to join Vanessa and Duncan in France, and is delighted with a haircut – “I am short haired for life” she says! With everybody it seems away, she is immersed in her work – reading copiously, writing about Forster (to be incorporated in her essay “The Novels of E.M. Forster”) and fiction; fantasizing about making money – for Greece, a new car; some revising of proofs of To the Lighthouse for the US and a French translation. Monday 28th February brings a “stream of thought” that runs the gamut: from Clive to Mrs. Woolf to Vita; to contemplation of trips abroad, of the rain and London and a respite from the constraints of “society”; to sorely missing Vanessa and the coming of Spring; to wanting to write more “lives”; then, ending:

Today I bought a watch. Last night I crept into L.’s bed to make up a sham quarrel about paying our fares to Rodmell. Now to finish Passage to India.

Vol. 3 [p.130]

During March, Virginia is excited about going to Cassis and then on to Sicily and Rome at the end of the month. On 14th March she is annoyed at not hearing from Vita, and in the wake of being done with To the Lighthouse is “blank of ideas” and I am particularly struck by her comment;

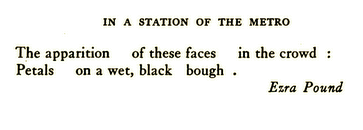

I toyed vaguely with some thoughts of a flower whose petals fall; of time all telescoped into one lucid channel through wh. my heroine was to pass at will. The petals falling. But nothing came of it.

Vol. 3 [p.131]

I surely could not be alone in recalling immediately Ezra Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro”; the quintessential Imagist poem they say of it, and a star in the annals of literary modernism. (Is Woolf thinking this too – either consciously or subconsciously?)

Pound says: “In a poem of this sort one is trying to record the precise instant when a thing outward and objective transforms itself, or darts into a thing inward and subjective”. Woolf says, and I repeat: “…of time all telescoped into one lucid channel through wh. my heroine was to pass at will.” A not dissimilar description of how to encapsulate a moment with words. A focus on time as much more than a mechanical measure is, I know, a hallmark of the modernist movement but this parallel remains of interest to me.

[By recollection, I can only say Pound is mentioned by VW mostly only in the midst of an Eliot discourse, and usually in the same breath as Wyndham Lewis who she clearly disdains. In respect to Lewis, I think in her letters there is mention of his falling out with the Omega Workshop, but I don’t recall that she met either Lewis or Pound. But on Monday 10 December 1917 she notes in her diary that she was “… reading a life of Gaudier Brzeska” [Vol. 1 p.90] and a footnote reveals this to be “Gaudier-Brzeska. A Memoir” by Ezra Pound (pub. John Lane, London, 1917), and from where the above linked quote comes (available to download at the Internet Archive.) Henri Gaudier-Brzeska was a French painter and sculptor; his Wikipedia entry informs of his short, tragic life (killed in the First World War at only twenty-three years of age) and his involvement with the Vorticism movement founded by Lewis and with which Pound also became very involved. I remain alert for further mention on Pound and Lewis !]

Less earnestly, VW contemplates wanting to “kick up [her] heels”, and sketches out some ideas which will find there way in some form or other into Orlando and The Waves [p.131]. The rest of the month is spent preparing for their holiday – she remembers going to Italy with Clive and Vanessa in 1908 and 1909 but never with Leonard. Edith Sitwell came to tea prompting a wonderful portrait.

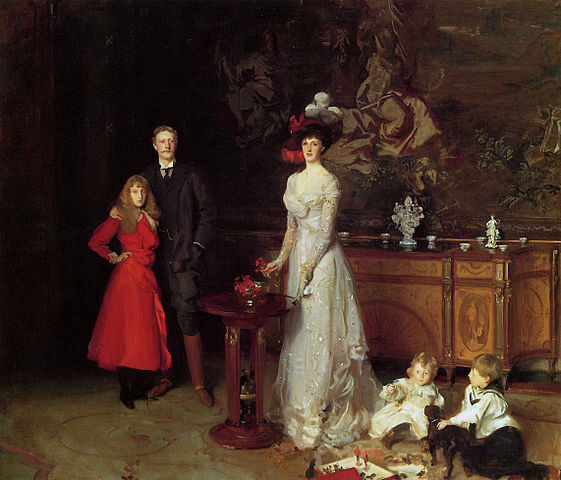

[…] transparent like some white bone one picks up on a moor, with sea water stones on her long frail hands which slide into yours much narrower than one expects like a folded fan. She has pale gemlike eyes; & is dressed, on a windy March day, in three decker skirt of red spotted cotton. She half shuts her eyes; coos an odd little laugh […] very tapering & pointed, the nose running on like a mole. […]She is a curious product, likable to me: sensitive, etiolated, affectionate, lonely […] In other ages she would have been a cloistered nus; or an eccentric secluded country old maid. It is the oddity of our time that has set her on the music hall stage. She trips out into the Limelight with all the timidity & hauteur of the aristocratic spinster.

Vol. 3 (pp.132-133)

According to Woolf, Sitwell flattered her as “a great writer”, spoke on her famously not very stable mother, and the footnote informs of her “miserable childhood and youth”. When the words of Woolf do not suffice more painterly versions (from Wikipedia) below.

John Singer Sargent: Edith, Sir George, Lady Ida, Sacheverell and Osbert 1900

From the editor’s note on page 133: The Woolfs left for Cassis via Paris on 30th March, where they stayed at the Hotel Cendrillon; though most of their time was spent with Vanessa and Duncan and Clive. They went by train from Toulon to Rome on 6th April, and then to Palermo for five days before going to Syracuse. Returning, they spent three nights in Naples and a week in Rome. They were back at Tavistock Square late on 28th April. [Interesting suggested cross reference are letters from her travels (especially those to Vanessa): VW Letters Volume 3 (nos. 1741-7)]

Sunday 1 May 1927: Virginia reflects on the joys of the anonymity afforded them in Italy, which is a measure of how her celebrity had grown in recent years. Her joy in the time just past is barely tarnished by a sick Nelly or the flutter of nerves at the impending publication of To the Lighthouse. Published on 5 May, she notes on the same day a tepid, unsigned review in the TLS but also impressive orders. Over the next days, Clive returns from Cassis – depressed and disillusioned – and Vita from Persia and, for one who stated she no longer cares about reviews or even her friends’ opinion, is extraordinarily eager to know all and everybody’s opinion! Vanessa sees their mother resurrected. Any wonder, then, that by Monday 6 June Woolf has been in bed a week with headache, etc. It is Whit Monday and a Bank Holiday, it is a “horrid dull damp” day, but her book is already heading towards a reprint. She reports on an undergraduate talk she delivered at Oxford on 18 May (with Vita in tow) – titled by her as “Poetry, Fiction and the Future” it was to be published by Leonard under the title “The Narrow Bridge of Art” as the opening essay of the posthumous collection Granite and Rainbow (here at the Internet Archive) and footnoted by LW as originally published in the New York Herald Tribune on August 14 1927. And, we hear Lytton Strachey is in love again (the footnote says it to be with Roger Senhouse, and to be Strachey’s last) [p.138] and together they talked about a recently published biography of Oscar Browning, an Apostle and house master at Eton, from which (citing the story about “the rescue of a stable boy” ) she would later draw in her fierce dissection of the patriarchy – better known as a A Room of One’s Own.

This June month begins with “headaches” and then convalescence at Rodmell. The calm and warmth there invigorates Virginia’s imagination and, beginning with thoughts of moths flickering of an evening and disturbing streams of thought, matter, experience, all the ideas are beginning to take form that will find voice eventually in The Waves. She sees Vita and Vanessa, and Clive’s father dies. But mostly it is an unusually quiet beginning to the summer season in London, and she is glad of it. And Adrian comes to tea, and she believes he is improving with age! Like them all. “So we Stephens mature late […] Think of my books, Nessa’s pictures – it takes us an age to bring our faculties into play.” [p.141]. The month ends with a wonderful account [pp.142-144] of a train trip from King’s Cross to North Yorkshire which lay within the band of a total eclipse of the sun. [The footnote on p. 142 says this event on 29 June 1927 was the first visible in Britain for over 200 years and special trains were organized for the occasion.] Virginia and Leonard were in a carriage with the Nicholsons, that is Vita and Harold, Quentin is with them, Saxon Sydney-Turner – who I can’t remember her mentioning for some time, and Ray Strachey.

Monday 4 July: The weekend was spent amongst the opulence of the Nicholson’s “Long Barn” home. Conversation was lively and snobbish – Empire, Leonard’s unjust criticism of the aristocracy. Virginia enjoys observing Vita on her home territory – instinctively gracious, glowing but without “novelty or adventure” (as, too, her poetry), and she is not convinced of her intelligence. Also ‘waves’ seem to now dominate her metaphorical bag of tricks; for, Vita is

“a ship breasting a sea.[…] with all sails spread. […]She never breaks fresh ground. She picks up what the tide rolls at her feet […]

[p146]

Again, she remarks that Vita’s world does not have what they (I guess she means she and Leonard, but also her friends, I suppose) enjoy – “some cutting-edge; some invaluable idiosyncrasy, intensity” [p.146]

Entries for July 1927 and Virginia’s preoccupations are marked by the motoring fad embraced by them all; there are new cars – a Renault for Nessa and a Singer for the Woolfs. For the moment at least, Virginia is enthusiastic in her driving endeavors. She is irritated by Clive’s mercurial moods – at once depressive and egotistical. To date, though, the summer has pleased her – her work and its financial rewards, her stable health, Vita. She looks forward with a positive demeanor to Rodmell; completing her book on fiction, getting stuck into that “moths” idea that has so rooted itself in her literary mind.