DIARY X: 25 january 1921-19 december 1921

HOGARTH HOUSE, RICHMOND.

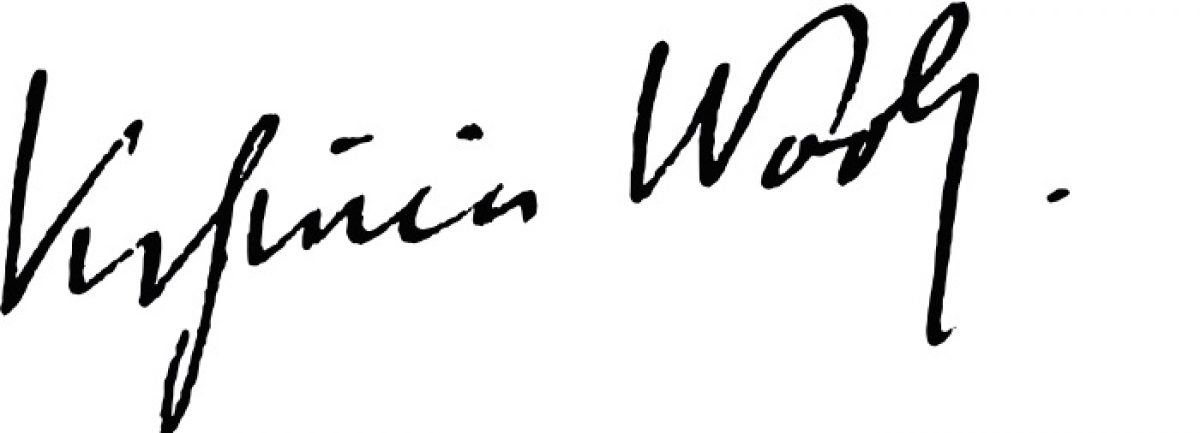

Tuesday 25 January 1921: Twenty-five days in before she begins her new year’s diary, and fittingly it is her birthday – “…not unfortunately my 25th, but my 39th…” [pp. 86]- how more and more irksome the passing years are becoming to her. Flowery and not so flowery words on Clive’s new and old loves, on Murry and Sydney, and Mansfield’s triumphs. [p87] Strachey asks Woolf’s permission to dedicate Queen Victoria to her which she grants in her inimitable style:

And to “Virginia Woolf” it was made! (See the above linked to original edition at the Internet Archive.)

This all neatly spills over into her 31 January entry that looks back on their visit to the farm at which Leonard’s youngest brother Philip was training as a manager, and to the nearby Tidmarsh, and the complicated Strachey, Carrington, Partridge arrangement, and Lytton’s depression and her middle-age. On their return to London the Woolf’s have a first Russian lesson with Kot, VW can finally see an end to Jacob’s Room in sight, and books to review are turning up at a do-able rate.

A Memoir Club meeting in early February offers a pair of highlights. Firstly, Clive’s reminiscences of his affair with a Mrs. Raven-Hill; & VW’s wonderment that this should have coincided with his overtures towards her (& only two years after his marriage to Vanessa), and noting further that Raven-Hill is now “imbecile”, whether the implication is that Clive drove her in that direction I couldn’t say! Maynard Keynes offered up a piece covering some of the difficult negotiations surrounding the Paris Peace Conference entitled “Dr Melchior” – beyond the politics of it, VW was impressed by Keynes’ character portraits of not just the subject but many of the players. (Note: this memoir along with a portrait of G.E. Moore was published in Two Memoirs, pub. Hart-Davis, 1949, and I have come upon its relevance into much more recent times with a Niall Ferguson kerfuffle (!) arising from his insinuation that Keynes’ diplomatic work at the Conference was effected by his attraction to Carl Melchior.) [pp.87-90]

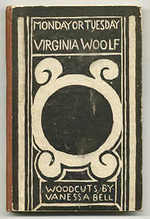

Through February and March VW juggles her social agenda (for instance, a farewell dinner for Murry before he leaves to join Katherine in France) with that of work, and now also her sometimes enthusiastic and sometimes not pursuit of Russian (with Leonard & Kot). She is alternately rejuvenated by visits to Rodmell and dissatisfied with the “look” of Monday or Tuesday, she opines out loud that Forster is lost forever to India [pp. 95-96], and she ponders the sometimes evolving and sometimes stagnating friendship with Eliot [pp.103-104]. At the end of March the Woolfs spend a week near Zennor in Cornwall and a loose entry with a description of the landscape is attached to her main diary [p.105].

Friday 8 April finds VW unable to concentrate and get back to Jacob’s Room because of a “scrappy” and clumsily placed review of Monday or Tuesday in the TLS as opposed to the fulsome one, both in scope and word, given to Lytton’s Queen Victoria; leaving her career, to her mind, in ruins! In the days after her emotions follow a roller coaster course, that she herself identifies, determined on the reviews she receives and the rather absurd competition she construes with Strachey – I mean what they do is just not the same thing! (And she did get the dedication that she sought!) Friday 15 April finds her “lying recumbent all day reading Carlyle” [p.110] presumably with the sole intention of affirming (for her self) that he wrote better than Lytton Strachey. On Friday 29 April Woolf relates a conversation with Lytton on his work and hers, their respective places in literary life, on history and biography – how precise or imagined this is I am not sure; perhaps things said that she would like to have said and to have heard from him.

Monday 23 May: Begins with the news that Carrington has become a Partridge; which amuses, or rather bemuses, and then returns to her own person. Woolf describes her restlessness, dissatisfaction; wonders whether others have these unsettling feelings that define her existence. She goes into London, she reviews. She thinks too much. She thinks about reading:

I’ve a notion of reading masterpieces only; for I’ve read literature in bulk so long. Now I think’s the time to read like an expert. Then I’m wondering how to shape my Reading book […] how I enjoy the exercise of wits upon literature- reading it as literature […I] can do this better for having read […] such a lot of lives, criticisms, every sort of thing

Vol. 2 [p.120]

And the footnote on this page says that the Reading book spoken of is in fact the first reference Woolf makes in her diary to what is to become the Common Reader!

Tuesday 7 June: A revealing dialogue with Eliot, suggesting he shares with the Woolves many of their misgivings towards Murry (who had just slammed Leonard & Kot’s Tchekhov translation). Virginia is delighted that Eliot found some nice words to say about Monday and Tuesday – thumbs up to “String Quartet” and “Haunted House”, not so to “The Unwritten Novel”- and that she could discuss writing openly with him. He also tells her that he considers Ulysses “prodigious”.

An editorial insertion reveals that VW had a sleepless night after going to a concert on 10 June, and on the following day remained in bed with a headache; this was to be the beginning of two months of what Leonard referred to as “a severe bout” of ill-health. They went to Rodmell from 17 June to 1 July and returned there again on 18 July.

Monks House, Rodmell…

Monday 8 August, and in Virginia Woolf’s own words:

What a gap! How it would have astounded me to be told [on June 7th] that within a week I should be in bed, & not entirely out of it till the 6th of August – two whole months rubbed out – These, this morning, the first words I have written [since]…days spent in wearisome headache, jumping pulse, aching back, frets, fidgets, lying awake, sleeping draughts, sedatives, digitalis, going for a little walk, & plunging back into bed again – all the horrors of the dark cupboard of illness once more displayed for my diversion. Let me make a vow that this shall never, never, happen again…

Vol. 2 [p.125]

Of course we know that it does, and I quote this passage in full because I think it is really important to at least try to imagine how very, very sick Virginia Woolf must have been at times, and seen through that light how heroic her life and accomplishments then are. I must pull myself up sometimes when I find myself wondering about just how much more a healthy Virginia could have achieved, because I do suspect that her illness was a part of her (in contemporary parlance it may be said that she came to “own” her illness), and her wonderful literary voice a sum of all those parts, and while she didn’t live to old age she did produce an extraordinary amount of work over four decades.

The fidgets of the 18 August are done with by 10 September, though bemoaned is the state of her handwriting. Important, she says, is “…my recovery of the pen; & thus the hidden stream was given exit, & I felt reborn.” [p.134] It is my own emphasis here; for I note Woolf’s recognition almost in passing of a stream of consciousness that was to soon become a hallmark of her prose. On 12 September not very favorable judgement is passed upon Henry James’ The Wings of the Dove (1902) – she doesn’t exactly call it pretentious, but that’s what she seems to imply – and one is somewhat surprised that she is reading this, apparently for the first time, almost twenty years after its publication. Not so surprising however is her verdict on the work of her father’s contemporary and friend when one considers her 22 October, 1915, letter to Lytton Strachey:

…Please tell me what merit you find in Henry James…and I read, and can’t find anything but faintly tinged rose water, urbane and sleek, but vulgar, and pale as Walter Lamb. Is there really any sense in it? I admit I can’t be bothered to snuff out his meaning when it’s very obscure…

The Letters of Virginia Woolf, Vol. 2, p.67

On Wednesday 28 September VW gives short shift to a visit from Eliot – of whom she is no longer afraid! The Woolves return to Richmond on Thursday 6 October.

Hogarth House, Richmond…

Tuesday 15 November: Virginia Woolf explains away her laxity towards her diary with assurances of her hard work and routine. And then she writes with pride:

The day before this I wrote the last words of Jacob – on Friday Nov. 4th to be precise, having begun it on April 16 1920: allowing for 6 months interval due to Monday or Tuesday & illness, this makes about a year.

Vol. 2 [pp.141-142]

She follows this with two comments relating to matters on her mind. Firstly, her struggles with a review of Henry James’ ghost stories for the TLS (I wonder whether her September reading of him was done so as a preparation for this), and secondly, a return to her thoughts about her “Readings” project (see May 23, 1921). In this case VW expresses her wish to tackle the Paston letters, and I’ll say here that from this eventuated the essay “The Pastons and Chaucer” which does in fact open the The Common Reader.

Friday 25 November is Leonard’s 41st birthday; if Virginia has noted his birthday before, I have missed it. So I do so herewith. On Friday 2 December VW dined with Bertie Russell from whom “she got as much out of […] as [she] could carry” [p.147] including this exchange:

-If you had my brain you would find the world a very thin, colourless place. – But my colours are so foolish I replied. – You want them for your writing, he said.[…]

– God does mathematics. That’s my feeling. It is the most exalted form of art. – Art? I said.- Well theres style in mathematics as there is in writing, he said.[…]

Vol. 2 [p.147]

An annoying spat develops with Bruce Richmond over her TLS Henry James article and the use – her use – of the word “lewd”, but as another year wraps up, Virginia strikes a positive chord with new writing and editing commissions for Leonard and good Hogarth sales. Last words: “All very good.” [p.152]