Diary V: 27 July 2018-12 november 1918

Hogarth House, Paradise Road, Richmond.

NPG Ax141255 © National Portrait Gallery, London

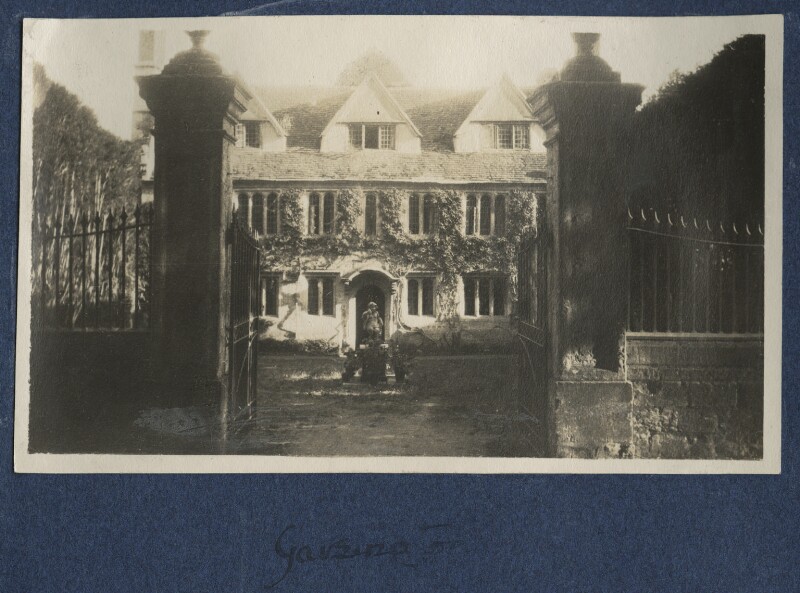

Monday 29 July: Another wonderful discourse of the joys of a weekend with Ottoline at Garsington – fine weather, finer food, perfect garden, endless walks and talks – “some million words [said] … listened to a great many more” [p.173] An interesting Mrs. Hamilton (& as I have just discovered, later to become a Labour Party MP) is introduced, a founding member of the 17 Club & (surreptitiously) overheard for the first time by VW at the club just days before.

Visiting Mark Gertler’s studio, Woolf is shown his “…teapot” (now in the Tate Collection) and, as previously (see June 24 above), the meeting leads to rather unflattering comments on his person and his art. She seems to have concluded that Gertler compensates for his artistic deficits – primarily, an obsession with “form” – with intractability and self-possession. Personally, I rather like his teapot

CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported)

On Wednesday 31 July the Woolfs decamp to Asheham. (A longer summer sojourn it seems.) Unusually, she takes her diary with her this time, and so there is an immediacy (and lightness) to her writing that is often missing in those entries written after the fact. During the first weeks of August there are passages of interest including Virginia’s reading of Byron and Christina Rossetti [pp178-181], a curt dismissive of Mansfield’s Bliss, and she mentions the parallel writing in her Asheham diary of all things domestic and in the fields of nature [p179]. She alternately bemoans the lack of visitors (Friday 8 August) and how to avoid them once they are there (Monday 19 August). Into September, brother Adrian and his wife Karin, visit (& are those to be avoided!) and there is a stunning entry dated Wednesday 18 September on the visiting Webbs. October comes, and soon V & L are back in Richmond and a London social life begins again – with Vanessa & Duncan & Clive, Maynard, Roger; she meets the Sitwells [pp201-202]- and Leonard’s editing and politicking and the war (and the peace) predominate. A quarrel concerning Mary Hutchinson (Clive’s lover & Lytton Strachey’s cousin & to become whether she liked it or not a constant in VW’s life) irritates her madly – the matter of who (Virginia) said what (that Vanessa didn’t care for MH) to whom (Gertler – a guest at Asheham at the end of September) is in her (VW’s) opinion totally overblown (“My conscience is clear … friendships maintained in this atmosphere are altogether too sharp, brittle, & painful.” [p.208]). On Monday 28 October the casual mention of “…a letter from Eliot asking to come & see us”. A footnote identifies Thomas Stearns Eliot and that this would lead to the first meeting between Woolf and T.S. Eliot. [p.210].

Monday 11 November 1918: Days before came surrenders and expectations and Wilhelm II going into exile in Holland, and then the Armistice – in the words of Virginia Woolf:

…the guns went off, announcing the peace. A siren hooted on the river…The rooks wheeled round, & were for a moment, the symbolic look of creatures performing some ceremony, partly of thanksgiving, partly of valediction over the grave. A very cloudy still day, the smoke toppling over heavily towards the east; & that too wearing for a moment a look of something floating, waving, drooping

[Tuesday 12 November]

[Should have left it with the rooks and smoke]…up to London…A fat slovenly woman…shaking hands with two soldiers…half drunk. But she & her like possessed London…staggering up the muddy pavements in the rain…Taxicabs were crowded …& yet there was no centre, no form for all this wandering emotion to take. The crowds had nowhere to go, nothing to do; they were in the state of children with too long a holiday. Perhaps the respectable supposed what joy they felt; there seemed no mean between tipsy ribaldry & rather sour disapproval …standing in queues, every one wet, many shops shut …& in everyone’s mind the same restlessness & inability to settle down, & yet discontent with whatever it was possible to do.

Vol 1. pp.216-217

Woolf’s words do not exactly hit the celebratory tone one would have imagined as the Great War ends; perhaps they (who were well informed) had over the last months of negotiations become use to the idea of an imminent peace. The disparaging snob certainly comes again to the fore, but perhaps also a latent recognition of shared emotions struggling to find release, and maybe, if she had thought about it, also shared losses and griefs that knew not “class” nor reason. Fittingly perhaps, this book (Diary V) ends here.