diary xv: 8 February 1926-23 january 1927

52 TAVISTOCK SQUARE, LONDON.

Either the German measles or influenza, or so Woolf muses on Monday 8th February 1926 in her new diary, as the reason for not writing sooner. Or, further; Vita? Or, just not having been inclined to make a new book in which to write? And this leads to a wondering as to the fate of her scribblings – and sixty as the age in which she would write her memoirs. How close she came we know. That eleven years after its first publication, Harcourt Brace is to republish the Voyage Out to her mind trumps Middleton Murry’s assertion that her work has a ten year shelf life. (In the Adelphi, Murry writes an article called “The Classical Revival” [9 February 1926] in which he pairs Jacob’s Room and Eliot’s The Waste Land as failures that will not be read in years to come. Ouch!) On 24th February when a conversation with Rose Macaulay and Gwen Raverat turns to her parents, Woolf thinks to herself about how recognisable Leslie and Julia Stephen will be in To the Lighthouse. Just a reflection, or is she perturbed at the repercussions of exposing the familial foibles? And on 27th February reading Beatrice Webb’s memoir My Apprenticeship (extraordinarily still in print or may be borrowed from the Internet Archive here; her complete diaries are accessible at the LSE Digital Library) encourages her to reread some of her own diary and reflect upon her person, her life – and even her “soul” – and bemoan (unlike the formidable Mrs. Webb) not having a “cause”. Contentment, yes, but purpose?

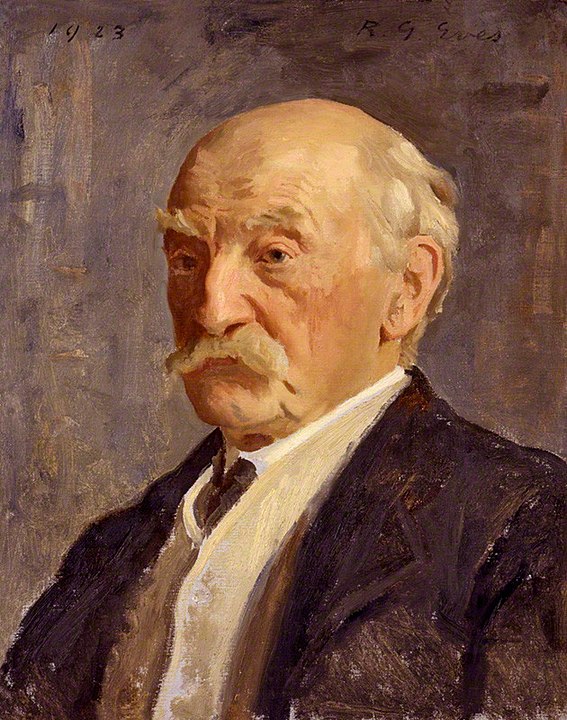

NPG x120542© National Portrait Gallery, London

Through March, teas and dinners and parties, provide an opportunity for the working writer to practice putting to word her observations – razor sharp descriptions of George Augustus Moore (on 9th March): “…pink foolish face; blue eyes like hard marbles; a crest of snowhite hair; little unmuscular hands; sloping shoulders; a high stomach…speaks without fear or dominance…in spite of age uncowed, unbeaten, lively, shrewd…”[pp.66-67] and Lord Ivor Spencer Churchill (on 20th March): “…an elegant attenuated gnat like youth; very smooth, very supple, with the semi-transparent face of a flower, & the legs of a gazelle, & the white waistcoat & diamond buttons of a dandy, & an all American desire to understand psycho-analysis…”[pp.67-68] On the latter, you can make up your own mind; suffice to say, not much more need be said of the dangers attached to falling under the ever alert writer’s gaze of Mrs. Woolf.

On Sunday 11 April, VW is still reading “Mrs. Webb” and still comparing their respective lives:

The difference is that she is trying to relate all her experiences to history. She is very rational & coherent. She has always thought about her life & the meaning of the world. She has studied herself as a phenomenon. Thus her autobiography is part of the history of the 19th Century. She is the product of science, & the lack of faith in God; she was secreted by the Time Spirit. Anyhow she believes this to be so; & makes herself fit in very persuasively & to my mind very interestingly. She taps a great stream of thought. […] she is much more interested in facts & truth than in what will shock [& what should not be said]

Vol. 3 [p.74]

When reading Woolf, one cannot help but be alerted to a “stream” of anything, and it is interesting I think that VW recognizes in Beatrice Webb’s reminiscences a vibrant flow of ideas and fragmentary thoughts, more associated with literary writing and not unlike her own writing experiments, as one way of telling of a life. If I understand correctly, she suggests that Webb not only portrays herself as a product of her time, but that in essence she is that ‘time’ – as an entity in and of itself.

Fun facts (I think!) and association: The expression “Time Spirit” was used for the first time in the English language by Thomas Carlyle in the mid-19th cent. as the very literal translation from the German of “Zeitgeist”, and whether VW is quoting Webb directly, or it is her own interpretation and formulation I don’t know. Carlyle died the year before VW was born, but he was somewhat a contemporary (acquaintance? friend?) of Leslie Stephen and famous even in death, and she read him and was immensely interested in his wife Jane – see her essay “Geraldine and Jane” , first published in the TLS on 28 February, 1929, and later in The Common Reader Second Series.

Sunday 18 April: So headed, Woolf explains it to be very well Friday 30th April – “the last of a wet, windy month”, and goes on to describe their bus and train journey back from a stay in Dorset on the 18th. And the continuing “servant question”, that is, the ongoing dispute with Nelly. The completion of the first part of To the Lighthouse is reported, and remarks upon her “dashing fluency” in contrast to the “excruciating hard wrung battles” she had with Mrs. Dalloway.

The first days of May are clouded by the General Strike called on 2nd May in support of the mine-workers – for VW a rare occasion in which political matters dominate her days, even distract her. She observes the streets without buses, workers on bicycles, sold out shops, grocery shortages, lights turned off early, no newspapers; days becoming indistinguishable from one another. Maynard agitates for Hogarth to print a special edition of the Nation. On Wednesday 12 May the Strike is settled, only to be not entirely settled on 13 May – the TUC having agreed to terms rejected still by the miners. Things gradually return to normal and by 20 May Woolf has begun to lose interest: “…nothing need to be said about the Strike […] one’s mind slips […] what the settlement is, or will be, I know not.” [p.86]. She ponders instead her feelings for Vita (who has returned from Persia and is coming to lunch the next day) – just who is it that is in love with whom, and what is love anyway.

On Tuesday, 25th May, Virginia’s mind is on Vanessa whose 47th birthday approaches, but who is off gallivanting in Italy. Titillating; the news from there of Duncan having been fined for “committing a nuisance”. The mind boggles. The second part of To the Lighthouse has already been “sketchily” completed, and Woolf sees a writing speed record on the horizon. And she reflects on Vita’s return the week before, and how oddly disillusioned she feels by her appearance and manner, but imagines that she probably affects Vita likewise and sees in this mutuality a solidifying of their relationship beyond the first throngs of romance.

Wednesday, 9th June, 1926: Virginia informs us she caught the ‘flue’ at Lords watching the cricket with Leonard, or ‘nerve exhaustion headache’ as she referred to it in her letters (Vol. 3 no. 1646) [p.90]; the latter suggesting her state to be attributable more to her work and the excitement of Vita’s return. For the Yale Review she is writing up “How Should One Read a Book” (remarkably, to be found here) from her January 30th lecture at Hayes Court, and still fretting over the essence of To the Lighthouse. And by the bye mentions that the Strike continues! On 11th June, Virginia is sufficiently recovered and she and Leonard go to Rodmell, and on the Sunday are joined by Vita. Leonard returned to London on Sunday afternoon; leaving Virginia and Vita alone until Tuesday.

On the last day of June, much ado about a hat and merciless teasing (“humiliation” she says) by Clive and Duncan, and on the first day of July she is still carrying the burden of her shaming, but more interesting is (probably) her first meeting with H.G. Wells and his wife Jane (at Maynard Keynes’s). She is not impressed. More interested she was in her Garsington meeting with Robert Bridges, and then visit with at Boar’s Hill near Oxford, on 26-27 June – she liked his poems well enough but more importantly found him to be “so obliging & easy & interested” – qualities she liked in others and at least tried to aspire to in herself; with varying degrees of success. (I note here, that recently I was reading about Gerard Manley Hopkins, and learned how it was Bridges that was solely responsible for his friend’s posthumous fame. At the aforesaid meeting, VW asks to see the Hopkins manuscripts, and the footnote 4 [p.93] says that the Woolfs indeed ended up owning one of the only 750 copies originally published by Bridges – and which sold at Sotheby’s in 1970.)

Sunday 4th July: Irrespective, and probably out of courtesy and more at Leonard’s behest, Wells lunched with them the next day (2nd July), gratefully with Desmond MacCarthy also present. Full of himself; disparaging of former lovers – Rebecca West, Dorothy Richardson; compares a reading of Proust to a visit to the British Museum; dismissive of James, Hardy; ponders doing away with Sundays.

Sunday 25th July: Long, descriptive entry of the Woolf’s 23rd July visit with Thomas Hardy in Dorchester. (Arranged by Forster.) Just a couple of years before his death, the tea chatter rambled and spluttered along, and though he spoke of others – Forster, de la Mare, Huxley – and warmly of Leslie, on his own writing Virginia was unable to draw much out of him. Not what the writer Woolf was hoping for anyway. And besides, it was clear, it was Mrs. Hardy who controlled the direction and extent of conversation.

An editor’s note explains that VW spent the night of Monday 26th July 1926 at Long Barn with Vita, who the next day drove her to Rodmell. Leonard joined Virginia there; having driven from London with Clive and Julian. During her summer hiatus Virginia concentrated it seems on “To the Lighthouse”, and socialized only infrequently – Raymond Mortimer stayed for a weekend, and they visited Maynard and Lydia at the Tilton farm that they had recently leased, followed by a party and fireworks for Quentin’s birthday at nearby Charleston. Until the beginning of September, Virginia’s diary is a series of occasional headed notes. An experiment in form – an attempt to catch the immediacy and sensations attached to a particular moment. (Perhaps she means that fleeting moment before a thought, an observation, is rationalized and given worldly contour and in doing so loses something of its essence.)

In the first week of September Virginia returns to a dated format. On 5th September she is pondering how to conclude To the Lighthouse – the last chapter will begin tomorrow and in three weeks her revisions (so she plans anyway!). Also, she is thinking about her theory of literature book for Hogarth, and it is worth a quote here of her intentions:

Six chapters. Why not groups of ideas, under some single heading …Symbolism. God. Nature. Plot. Dialogue. Take a novel & see what the component parts are…[examples] of books which display them biggest. Probably […] pan out historically. One could spin a theory which wd bring the chapters together.

Vol. 3 [p. 107]

And ‘Outlines’ she must do – “a bunch of” – and, as commissions for reviews come her way. And the money from these are important! She mentions as an aside that “under a new arrangement, we’re to share any money over £200 that I make” [p.107] – an interesting glimpse into the “professional” Woolfs. (Whether the same divvying up applies to Leonard’s earnings she doesn’t say …!) On one hand, she says she is “frightfully contented”, on the other she admits that Maynard and Nessa make her person and her gifts seem rather mediocre, and Nessa’s children remind her of what she has been denied, but having aired her grievance, she puts her envy aside (I love how she is able to do that, how short lived her moments of regret) and recognizes the freedom and possibilities in her life, and says: “Hence, I come to my moral, which is simply to enjoy what one does enjoy, without teasing oneself …” [p.107] On the previous day, a most successful visit from Clive and Mary, that left her with the thrill of “being liked by Mary” a “sense of great happiness”. [p.108] (I can’t help but be curious about one of the topics of conversation; a questionnaire on religious beliefs in the August and September 1926 issues of The Nation and Athenaeum [footnote p.108] extending from the energetic reaction to Leonard’s provocative contention in his column; that in religious matters, skepticism, atheism, agnosticism were the default of the educated modern “man”. I can’t find either LW’s original piece nor the questionnaire issues, but Virginia Woolf and the Literary Marketplace an anthology by J. Dubino has an interesting chapter [at Google Books – maybe!] by Elizabeth Dickens that explains the controversy and at least includes the latter.)